Beelzebub in New York

Beelzebub in New York, book devils, 1875

Yet another school devil/possession panic has hit the headlines, this time in Peru, where the children are seeing visions of a Man in Black. Schools tend to be incubators for panics and, although they may merely reflect a societal sense of Doom, news reports of possession panics are on the rise. For example, recently we’ve seen reports from Malaysia of a “female vampire” terrorizing a girl’s school. Let us visit New York’s East Side for a look at a series of devil panics from the late 19th century.

PANICS OVER SATAN

New York School Children Scared Over Suspected Visits From Beelzebub

THREE STRANGE CASES

Superstitious Little Ones Trample Each Other in Mad Stampedes of Fear.

LATEST OF THE SCARES

The Cry of a Pupil in a Grammar School Caused a Disastrous Rush for the Street.

By Long Distance Telephone.

New York, June. 19. A remarkable series of panics have occurred in public schools during the past week and now the teachers all over town are nervously fearful lest their schools should have a similar experience. In all cases the trouble has arisen over a crazy story to the effect that the devil was in the school or else projected a visit there.

A week ago yesterday in the grammar school at Mulberry and Bayard streets, a little girl stirred up all the girls by professing to have seen a ghost with horns and three eyes, and yesterday 1100 little girls, pupils in the primary department of Grammar School No. 4, at Rivington and Ridge streets, were thrown into a panic at the noon recess by one of their companions, a little Hebrew girl, who declared that she had seen the devil. [He was said to have appeared on the roof. Some articles mentioned that she had been told at home that the Devil would carry her off if she did not behave; if true, a strange threat in a Jewish household.]

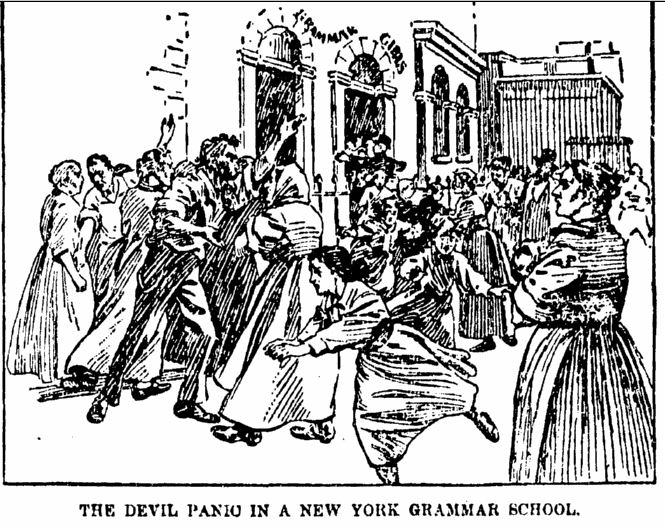

This panic became a riot, and the police had to club their way through a crowd of hysterical parents and friends to reach the school. Two of the policemen were knocked off their feet by the children and over fifty of the younger children were knocked down and bruised.

This morning there was a big scare in Grammar School No. 22, at Sheriff and Stanton streets.

Shortly before 9 o’clock, when the children were gathering in the playground one little girl sent up the cry:

“The devil’s in the school!”

Immediately there was a rush for the door leading to the street. One little girl was knocked down and several others fell on top of her. For a time the wildest excitement prevailed among the children.

Some unknown person who was passing the school building cried “Fire!” The residents in the neighborhood took up the cry, poured out of the houses and ran to the school where the children were. Soon a crowd of fully five hundred excited persons was gathered in front of the schoolhouse. Police from the Delancey and Union market stations were sent to quiet and disperse them.

The teachers of the school where the trouble occurred have been aware for several days of a superstitious feeling among the children. It is said the small children in all the east side schools have in some manner, during the past few weeks, become interested in talking to each other about the devil, and have exchanged stories they have heard from older persons on the playground.

The matter has progressed so far that the school authorities will take cognizance of it and suppress any further development of the superstition.

Philadelphia [PA] Inquirer 20 June 1896: p. 1

The scenes at the Grammar School at Houston and Sheriff streets were particularly dire.

One morning, less than 50 little girls were assembled in the basement playroom waiting for school to open. Suddenly a little girl dashed from behind a pillar and fled into the street, crying: “The devil! I’ve seen the devil!” Her companions dashed after her shrieking. One of them fell at the door, and before they could stop a dozen others tripped and fell upon her. No one was badly hurt, but the uproar was increased, and almost instantly a report spread through the neighborhood that something awful had happened at the school. The cries of the children seemed to confirm the report. The tenements poured forth a terrified mob of men and women, wild, bareheaded, breathless. They believed that their children were in danger and mobbed the school and attempted to force the doors.

“What is it?” They demanded fiercely. “What’s the matter? Where are our children?”

“It’s a devil!” a terrified girl piped up. “Mamie seen it!”

“No,” cried a man in the mob, “it’s fire; I see the smoke!”

“Fire! Fire!” the crowd yelled in horror. “Let the children out! Let us in!”

Still the tenements poured out terror-stricken parents and late school children. The street was blocked. The little girls who had run from the building were in danger of being trampled to death. The crowd itself, wild and clamoring, seemed to confirm its own worst fears. It howled in many tongues and rushed at the school doors.

These doors open outward, and the rush was easily checked. Two policemen tried to force the mob back, but for a time they were powerless. Then came proof of the value of school discipline. The larger boys, who had reached the school, had not rushed out with the frightened girls. They make up the school guard and have been drilled in the work of preserving order by the assistant principal.

The principal marshalled them behind his closed doors and gave them their instructions in a second.

“This is all nonsense, boys,” he said. “I want you to bring the little girls inside and quiet that crowd. Clear the sidewalk in front and tell them there is no danger and that no one is hurt.”

The boys, led by their captain, Harry Leon Kringle, opened the front door and dashed out. Their organized rush forced back the men and women on the sidewalk. They rounded up the little girls, and, saying to each, “the principal wants you inside at once,” pushed them into the school, where they were lined up and reassured by Miss Bell, their head teacher. The boy guards, 36 of them, cleared a space of sidewalk 75 feet long.

The principal closed the door again when the little ones were inside and devoted himself to the work of quieting the crowd. The teachers inside started a song, and the pupils joined until the chorus could be heard in the street. The effect was magical.

“Nothing has happened,” the principal said. “There is no cause for fear. It would be better if you were to disperse.”

“Let us in where the children are,” a sturdy Polack demanded. “Let us see for ourselves.”

“My friend, you must go away and be quiet,” the principal said.

“No,” the man shouted. “Let us in.”

The crowd, still fearful, was reassured by the singing, but still lingered. The principal beckoned to a policeman, and the leaders of the mob fled. After that the police, who had been re-enforced, soon dispersed the crowd.

And so by 9 o’clock the panic and riot were over and 2,200 children were at their desks. Beelzebub had been routed, but it was sharp fighting. The school guard, young as its members are, was of the greatest assistance. Daily Illinois State Register [Springfield, IL] 10 July 1896: p. 8

The author goes on to discussion devil-panics around the world with a few historical examples and adds:

Neurologists admit the ease with which the eyes can be deceived, either through fear, suggestion or auto-suggestion, and, furthermore, how such hysterical delusions are not only contagious, but when affecting large numbers are apt to become epidemic. Children, and girls especially, whose brains are particularly susceptible to psychic influences, and whose thoughts are easily guided either for good or bad, are perhaps most easily affected by visual and other hallucinations and delusions.

The East End schools reported a spate of panics spread across three decades. In October 1878, at Grammar School 13, No. 239 East Houston-st. there was a panic of undetermined origin among the 2,000 students: some said that a boy cried fire, others that a girl had fainted—faints are a well-known trigger for panics. An 8-year-old boy was badly trampled in the melee and windows were broken. In November of 1889, a panic began at Grammar School No. 4 at 203 Rivington Street when a girl had a seizure and there was a false fire alarm. Over 100 children rushed outside with bruises and torn clothing the major casualties. 1896 seemed to be the year specifically for devil-panics.

Due to major changes in New York real estate, it has been difficult for me to map the locations of the various panic-stricken schools, but as best I can judge by historic maps, there seems to have been a school every few blocks in the East End. What seems obvious is that there was a cluster of incidents, a contagion—the usual language of mass hysteria—that spread among the grammar and primary schools of this community. At this time, grammar schools were for children aged 10-14, a prime age for polts and panics.

The papers were severe on these ignorant immigrants. One assumes that the poverty and difficulty of life in the tenements and the stresses surrounding assimilation had some role to play, as the author commented in the article on the 1896 panics, couching it as that bugaboo of the educated American citizen: superstition.

The fear of Beelzebub is strong upon the miserable masses who constitute the population of New York city’s poverty stricken east side. Ignorance prevails there, and superstition is rife. Out of this universal superstition has arisen recently a remarkable series of devil seeing panics.

Now, having known a number of clown ministers in my career as church organist, I am not unacquainted with Evil incarnate. As a Fortean I would be remiss if I did not at least consider the possibility that some child saw the Devil at her school, although one suspects that whatever that frightened her had a more earthly taint. I hesitate to be dogmatic about the existence of evil entities—human or inhuman—with a taste for young souls. Still, would the Prince of Darkness really make time in his busy schedule to hang about, smoking, on the roof of a New York school? Or, for that matter, is Lucifer visiting schools in Nigeria, Peru, or Indonesia just to make teen-aged girls scream and faint, as if he was a teen pop idol on tour? (Well, Peru’s Man in Black is bearded like a hipster and he wants to touch the girls….)

Folklorists and sociologists have studied similar panics for centuries, labeling them “mass hysteria,” or “mass psychogenic illness” and ascribing them to various social pressures. Fair enough, but I still want to know how the physical mechanism works; how social pressures can make a community see ghosts or the Devil on the roof in a folie-à-choose-your-number.

This article discusses the issues of MPI and conversion disorder in the context of recent school panics and suggests that, in today’s global economy, the spread of panics is facilitated by social media.

In 1896, all it took was a little girl shouting of the Devil. And, unlike today, no exorcists were called in.

Other 19th or early-20th-century devil-panics? Send to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com, who is standing by with the smelling-salts.

See this site, and this, for the East Side’s often grim history and some good photographs, which give an idea of the squalid environment.

Beelzebub in New York Devil panic in New York grammar school

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her new blog at The Victorian Book of the Dead.