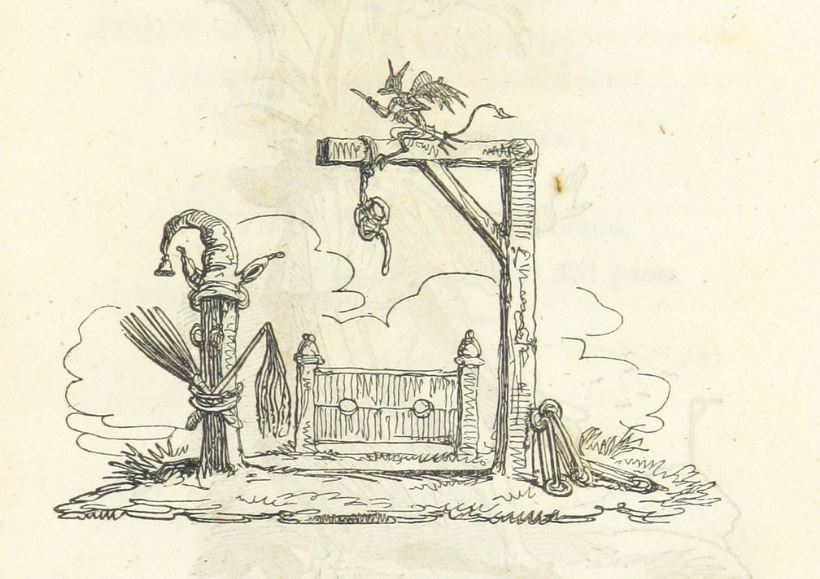

A Walking Gallows

This ghoulish story takes place during the Éirí Amach of 1798, the Irish rebellion against English rule. Inspired by the French and American Revolutions, a group called The United Irishmen rose against the English, but the Irish were defeated after three months of brutal warfare and atrocities on both sides. Lieutenant Edward L. Hepenstall of the County Wicklow Militia fought against the Irish insurgents in 1798 and, according to legend, earned for himself the nickname “The Walking Gallows” or (by some accounts) “Hanging Gallows.” This article is from 1908, but conveniently reiterates and quotes details from English papers of 1800 and Sir Jonah Barrington’s memoirs of 1827 in which he relates his experiences during the rebellion when he was a soldier and barrister.

A WALKING GALLOWS

The Horrible Deeds of Lieutenant Hepenstall.

HANGED MEN FROM HIS NECK.

This Handsome but Brutal Giant of the Wicklow Militia Was the Most Cold Blooded and Eccentric Executioner That has Ever Existed.Among the examples and records of British tyranny during the terrible year 1798 there is none more extraordinary, according to a writer in an English magazine, than that of Lieutenant Edward Hepenstall, known by the nickname of “the walking gallows,” for such he certainly was, literally and practically.

This notorious individual, who had been brought up as an apothecary in Dublin, obtained a commission in the Wicklow militia, in which he attained to the rank of lieutenant in 1795. He was a man of splendid physique, about six feet two inches in height and strong and broad in proportion. Referring to this handsome but brutal giant, Sir Jonah Barrington in his memoirs states:

“I knew him well and from his countenance should never have suspected him of cruelty, but so cold blooded and eccentric an execution of the human race never yet existed.”At the outbreak of the sanguinary rebellion, when the common law was suspended and the stern martial variety flourished in its stead, Lieutenant Hepenstall hit upon the expedient of hanging on his own back persons whose physiognomies he considered characteristic of seditious tenets. At the present day the story seems almost incredible, but it is a notorious fact, revealed by the journalism of the period, that when rebels, either suspected or caught red handed, were brought before him Hepenstall would order the cord of a drum to be taken off and then, rigging up a running noose, would proceed to hang each in turn across his athletic shoulders until the victims had been slowly strangled to death, after which he would throw down his load and take up another.

The “walking gallows” was clearly both a new and simple plan and a mode of execution not nearly so tedious or painful as a Tyburn or Old Bailey hanging. It answered his majesty’s service as well as two posts and a crowbar. When a rope was not at hand Hepenstall’s own silk cravat, being softer than an ordinary halter, became a merciful substitute.

In pursuance of these benevolent intentions the lieutenant would frequently administer an anaesthetic to his trembling victim—in other words, he would first knock him silly with a blow. His garters then did the duty as handcuffs, and the cravat would be slipped over the condemned man’s neck.

Whenever he had an unusually powerful victim to do with, Hepenstall took a pride in showing his own strength. With a dexterous lunge of his body the lieutenant used to draw up the poor devil’s head as high as his own and then, when both were cheek by jowl, begin to trot about with his burden like a jolting cart house until the rebel had no further solicitude about sublunary affairs. It was after one of these trotting executions, which had taken place in the barrack yard adjoining Stephen’s green, that Hepenstall acquired the surname of “the walking gallows.” He was invested with it by the gallery of Crow Street theater, Dublin.

At the trial of a rebel in that city the lieutenant, undergoing cross examination, admitted the aforementioned details of his method of hanging, and Lord Norbury, the presiding judge, warmly complimented him on his loyalty and assured him that he had been guilty of no act which was not natural to a zealous, loyal and efficient officer.

Lieutenant Hepenstall, however, did not long survive his hideous practice. He died in 1804 [other sources say 1799; still others 1800]. Owing to the odium in which he was universally held, the authorities arranged that his funeral should take place secretly, while a Dublin wit suggested that his tombstone would be suitably inscribed by the following epitaph:

Here lie the bones of Hepenstall.

Judge, jury, gallows, rope and all.

Van Wert [OH] Daily Bulletin 29 August 1908: p. 1

When he died, it was said that his friends concealed his death until after he was buried and his coffin was accompanied to St. Andrew’s Churchyard only by his brother and four hired pallbearers.

There are legends that Hepenstall died of a loathesome disease: morbus pedicularis, eaten by vermin, like King Herod, and that he was carried off at death by his familiar, a black cow.

Fact, propaganda, folklore? chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.