Caterpillar Lace and Spider Silk Gowns

While searching newspaper archives for the names of the jurors who acquitted the Copperhead murderer of an Abolitionist editor in Dayton and then supposedly went mad (yes, all twelve of them. And the judge…), my eye was caught by the headline “Caterpillar Lace.”

While searching newspaper archives for the names of the jurors who acquitted the Copperhead murderer of an Abolitionist editor in Dayton and then supposedly went mad (yes, all twelve of them. And the judge…), my eye was caught by the headline “Caterpillar Lace.”

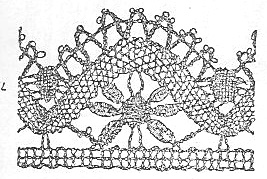

As a former vintage clothing dealer I thought I knew what the term meant. After all “chenille” is the French word for caterpillar. Chenille embroidery, with its fluffy texture, is a particular favorite of mine as are the chenille fringes on 1880s and 1890s cloaks, which I used to describe to customers as “tarantula legs.” A type of lace patterned with wide undulating bands was also called “caterpillar lace.”

But this article told of a startlingly different type of lace production:

CATERPILLAR LACE

Another case of self-destruction, among the number reported every day by the police of Paris, is that of a poor inventor, a native of Munich, who had set his heart on perfecting the curious caterpillar lace produced in some parts of Germany. This lace, which is said to be remarkably beautiful, is thus obtained: A paste, prepared from the leaves most in favor with these insects, being spread over a slab of stone, or any other smooth surface, the operator with a fine camel’s hair pencil, dipped in olive oil traces the portions of the design which are to be left uncovered by the little weavers; in other words, the interstices of the future fabric. The stone is then placed on the ground in a slanting position, a number of caterpillars being placed at its base. These insects, whose thread is remarkably fine and strong, at once begin to devour the paste, creeping upwards in search of it, and carefully avoiding the oil. As they crawl up, they spin incessantly; and their webs, enlaced together over the surface of the stone, form a magnificent tissue, excessively delicate, yet exceedingly strong. A veil thus fabricated, twenty-six inches and a half by seventeen, weighs but a grain and a half. Nine square feet of this novel tissue weighs only four grains and one third, while the same extent of surface of silk gauze weights one hundred and thirty seven grains, and of the finest thread lace two hundred and sixty-two and a half grains. The poor inventor had embarked all his pecuniary means in a factory destined to produce this lace in large quantities; his attempt was unsuccessful, and he shut himself up in his laboratory a few days ago, and put an end to his life by means of charcoal. Troy [OH] Times 10 September 1863

This was news to me. I quickly searched my costume collection databases for examples held in museums. Surely The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, or the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, or the V&A in London would have a veil or a shawl. But there seemed to be no surviving examples. And no mention of the lace at all.

Chandler Robbins Clifford, in The Lace Dictionary had only a brief definition: “Lace made by employing the natural web of the caterpillar, a freak lace only occasionally made by experimentalists; sometimes the spider is employed in like manner.” My other reference books on lace were silent on this interesting subject.

I returned to the newspapers and all was revealed. From roughly 1857 to 1909, the same article had been reprinted, with only slight variations and always as a current news item, telling of the man from Munich who had invented a unique insect industry. The 1863 article is the only one that mentions suicide. It is such a detailed account and such a strange subject to be a created as a journalistic hoax. Apparently certain species of caterpillar are death to silkworm colonies. It seems extremely far-fetched, but is this some bizarre metaphor for German ingenuity triumphing over traditional Japanese manufacture? Or did the leaves, eaten into lacy patterns by some caterpillars, inspire a flight of fantasy?

While the notion of caterpillar lace was startling enough. I was further surprised to find several articles on spider silk being used to make clothing. And not just garden-variety spiders, but giant Madagascar spiders, with golden webs.

DRESSES OF SPIDER WEBS.

[Chamber’s Journal]

The worm is proverbially the last of created things to turn against the tyranny of those who seek to coerce it, and the silk-worm is evidently no exception to the rule, for it has for ages been patiently laboring to gratify human vanity. No so the spider, however, whose beautiful silk has not yet been similarly applied, simply because that wily beast refuses to work to order. But a determined onslaught upon his pride and prejudices has been made in Madagascar, where a regular factory has been started to make silk dresses from spider web. The old difficulty has still to be faced, however, and time alone will show whether man or the spider is to be the victor. The spiders, who spin luxuriously in their native groves, sulk or fight or devour their young or otherwise amuse themselves when brought to the factory; but they will not work except just occasionally when the mood happens to strike them. Then they sometimes spin for days at a time, and die of overwork. Their habits and customs are being carefully studied, and if only they will do what is required of them they will be made as comfortable as circumstances will permit. Altogether it is the prettiest little parlor; perhaps the spider may yet be induced to walk in and favor the proprietor with those silk dresses for which the world is still waiting. Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 7 April 1906: p. 11

In all of the articles on silk-spinning spiders, the creatures are anthropomorphized and put into the context of early 20th-century gender stereotypes.

GOLDEN WEBS

Spun By a Giant Spider in Far-Away MadagascarAmong the great web-spinning spiders is the halaba, of Madagascar, which spins shining golden-yellow threads strong enough to bear the weight of one of those cork helmets such as travelers wear in warm countries. They have women suffrage in the halaba family, where the female considerably outweighs the males, and is correspondingly “bossy.” She grows to the quite remarkable length of five and a half inches, while he, poor fellow, never gets beyond the quite insignificant dimensions of an inch and a half. In consequence, when she, in all the glory of her shining gold cuirass, with a silvery down on it, spreads her five red, black-tipped legs in the midst of her shining gold web, he has to keep at a respectful distance, and seek the seclusion of his club, for he has no rights in that web which his more mighty spouse is bound to respect. She is a very industrious spinner, and I have no doubt that the airs of superiority she takes over her husband are largely due to the fact that she realizes she is the breadwinner for the family. She has been known to spin in a little less than a week 3,291 yards. For over 150 years men have tried to utilize the spider’s silk for weaving fabrics, but, with discouraging success. Le Bon, about the beginning of the last century, succeeded in making gloves of it, and Louis XV, had a pair of hose made of the thread. The webs of the halaba and one or two American spiders have led Dr. Wilder, of Cornell University, to hope that he might still make spider webs commercially valuable. The thread is quite as long as that of the silk-worm; one species in Jamaica spinning a thread sometimes three miles long, but the chief difficulty lies in obtaining a long thread unbroken. Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 8 December 1894: p. 1

Difficult, but not impossible, as the following astonishing link will show.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/g/golden-spider-silk/

SILK DRESS MADE FROM SPIDER WEB

One of the curiosities of the Paris Exhibition of 1900 will be a silk dress made entirely of silk manufactured from the spider’s web. This silk was made in Madagascar under the direction of the Jesuit, Father Cambue, and will not be exhibited merely as a curiosity, but in order to show the practical use to which the big Malagasy spider, known as the black spider, may be put. Father Cambue has been devoting himself for the last two years to solving the problem of utilizing the silk-spinning capacities of the spider. He has found in the Malagasy black spider a subject of practical usefulness and he has already a colony of spiders spinning the cocoon. The silk is much finer and lighter than ordinary silkworm’s silk. Father Cambue says that the black spider is not at all pleased when put to spin the cocoon, but that when well fed and supplied with plenty of drink, it can spin a really enormous quantity of thread. The spider is very fond of native brandy, and spins best when thoroughly drunk. When the cocoon is complete, the spider dies, but this is not of much importance, for the power of reproduction of the race is enormous. Oak Park [IL] Times 23 February 1899: p. 3.

Two stories of insect industry, both seemingly improbable. While stories about spider silk dresses circulated from about 1894-1900, the fiction (if fiction it is) about caterpillar lace was repeated at intervals, no doubt on slow news days, over the course of half a century. One might say the story had legs.

I know little about the habits of insects; can anyone wise in the ways of lepidopterous caterpillars tell us if there is any truth at all to the stories of caterpillar lace?