Corpse Contracts: People who Sold Their Own Dead Bodies

Corpse Contracts: People who Sold Their Own Dead Bodies

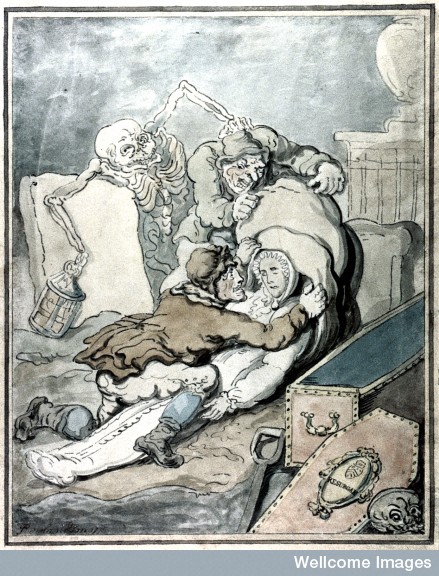

From the Wellcome Library collection.

The sun is shining, the weather is clement, the birds are chirping in the shrubbery, and it is altogether a grand day to be alive. On such a lovely day, one’s thoughts must, inevitably, turn to bodysnatching.

It is a sinister fact that, before the passage of the various Anatomy Acts, the doctors of the past paid for stolen corpses for their dissecting rooms. What is less well-known is that various individuals in what might be termed the “pre-corpse stage” sold their own bodies to the anatomists, assigning legal title to their mortal remains with an official document. One wonders if such contracts were valid if not signed in blood?

The temperate found many morals to point in these transactions.

THE BIRD OF DEATH DEAD

Demise of a Man Who Sold His Own Body to Buy Drink

Vienna, July 15. A man known as the “Bird of Death,” employed in the Vienna general hospital, met with a singular fate in the discharge of his gruesome duties. His name was Alvis Paxes. He was about 55 years old, and of herculean physique. For 33 years he carried all the corpses from the mortuary chamber, hence his weird name, which the hospital jesters gave him. He died to-day of blood poisoning caused by handling the body of a patent who died from an infectious disease.

Some years ago he sold for cash his own body to a museum manager and spent the money in drink. To-day his body was handed over to the purchaser. Pittsburg [PA] Dispatch 16 July 1890: p. 1

I expect the original German had the connotation of something like “carrion crow.”

This squib weighs whether the drink or the selling of his aged mother’s body was the greater sin. Whisky seems to have won out.

Sold His Body for Whisky

Cincinnati, Nov. 17. John Winkler, an old rag picker, who was found dead in his hovel, 608 West Sixth Street, this morning, was a peculiar example of the depths of degradation to which a human being may sink. For many years he was a familiar figure in the West End. For 10 years past it is very doubtful if he drew a single sober breath. He lived in the utmost filth and squalor, and when found dead in his bed had his clothes and boots on. Four years ago his aged mother died, and Winkler sold her body to a medical college. He also sold his own body to be delivered after death and squandered the money in whisky. The Somerset [PA] Herald 23 November 1887: p. 2

Some had seller’s remorse.

Trying to Buy Back His Own Body.

This queer story comes from Massachusetts: A man who lives in a suburb of Lowell is seeking to have a deed given by him twenty years ago recovered. The deed conveyed his body to a surgeon now practicing in Great Falls, N.H., for the sum of ten dollars and other considerations, possession to be taken on his death. Since the deed was made the giver has made a fortune in South America and has decided that he would like a Christian burial. The deed provides that the body shall be dissected and the skeleton articulated and presented to a medical university. The lawyers have decided that the deed holds good and that the only alternative is to buy off the doctor. The giver of the deed has made a big offer, but it has been refused. Hartford Courant. Daily Nevada State Journal 16 January 1892: p. 1

Others imposed on good-hearted physicians.

TWO HEARTS BUT NO CONSCIENCE

Police of Naples Looking for a Man Who Sold his Own Body to Physicians

NAPLES, April 3. The police of this city are looking for Giuseppe di Maggio, a freak possessed of two hearts, but, evidently, no conscience. Some time ago a medical institute of New York bought Maggio’s body to be delivered after death, for $8,000. With this money Maggio settled down in Naples and lived merrily on his capital, which was soon spent. He ingratiated himself into the favour of a wealthy landowner, whose sister he promised to marry. He pretended that he was to receive a large sum of money from America and supported his story with a fraudulent cablegram. On the strength of his story he borrowed money right and left, including his prospective brother-in-law, and then skipped.

Now a warrant is out for his arrest. The Evening Statesman [Walla Walla, WA] 3 April 1906: p. 2

Given the date, we may be permitted to doubt the strict veracity of this item.

Strange Freak to Get Money

Louisville, Ky., Dec. 5. Milton Clark, who is employed at the University of Louisville, medical department, to take care of the dead bodies brought to the place for examination, sold his own body yesterday for the thirty-third time to physicians for dissection. Whenever he is sore need of money he visits a physician interested in one of the various medical colleges and sells his body. Lawrence [KS] Journal World 5 December 1898: p. 2

Still others, like this sad lady, with the “checquered past,” sold their bodies to clear a debt. I have not yet found Annie E. Jones’s grave in Bridgeport, but Dr. John Cooke was a luminary of the Eastern Ohio Medico-Chirurgical Society.

A Singular Suicide

There has lived on Glenn’s Run and about Martin’s Ferry and Bridgeport, for the past few years, a queer, gnarly-looking little old French woman, named Annie E. Jones. Her past history has been varied, checquered and not altogether reputable. She had several children, all dead or wandering. She was twice married—the last time to a negro. By some of her children there came a granddaughter named Agnes Racine, a white girl, of rather prepossessing appearance, and together she and her grandmother lived at Martin’s Ferry, till a colored man, named Boggs, essaying to be a Baptist preacher, living in Bridgeport, concluding his Christian duty was to discard his wife and make love to Miss Racine. The tender emotion was reciprocated by Agnes, and Boggs quit preaching, began to vote the Democratic ticket—kicked his old wife out of doors, and took old Mrs. Jones, her granddaughter Agnes, and the illegitimate young one by her, to his home on top of the hill, south of Bridgeport, on Vincent Mitchell’s place, where they have since nestled. Having voted for Hancock, he next, it is alleged—so the old woman said to us the evening she suicide—he began to abuse her terribly, knocking her down and otherwise showing his high appreciation of his—grandmother—by his baby. It seems Agnes lent a helping hand also when necessary to keep the old woman in proper subjection. Time flew apace, and the old woman—who by the way, was rather a good French scholar and more perhaps than ordinarily intelligent—grew tired of her rations of abuse, and soured and sickened of life. This Boggs, as many of the Chronicles’ readers know, was charged with a tried for adultery with this Racine girl in St. Clairsville, and much to the regret of our people, was acquitted; since which time he has been living, it is alleged, in open criminality with the girl, though he claims to be married to her.

The old woman had contracted a bill with Dr. Cook, amounting to $17 for herself and Agnes. She had no money, and though Boggs abused it, she claimed to own, in fee, her mortal body—65 years old, not very comely, and weighing, perhaps, 80 to 100 pounds. She wanted to pay her debts, so she came to see her creditor, Dr. Cooke; he was not in, she went home, leaving a message for him to come up at once. He went, and she asked the doctor “what bodies were worth for dissection?” He replied it depended on certain contingencies. She then informed him she meant to deed him her body, after death, and as she meant to be honest, she would give him the paper just then. The doctor informed her such a transaction such as that must be regularly drawn up and acknowledged, and referred her to R.J. Alexander as a suitable person to “draw up the papers and make them full and strong.” So she proceeded to wash her clothes and her person, and all things being in readiness she visited Mr. Alexander at his office, when Mr. McDonald, Alexander’s partner, drew up at her request and had acknowledged the following deed:

Know all men by these presents, That I, Anna Eliza Jones, for and in consideration of seventeen dollars in hand paid, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledge from Dr. John Cook, of Bridgeport, Ohio, do hereby give grant and convey to said Dr. John Cooke my body after my death, to be disposed of as said Dr. John Cooke may desire, either for dissection by any medical college, or for his own private use for dissection. Said Dr. John Cooke to have immediate possession and control of my body as soon as life therein shall be extinct and wherever my body may be at that time.

It is hereby witnessed that the real considerable of this deed is the release by said Dr. John Cooke or his claim against me for medical professional services, for myself and granddaughter, Agnes Racine, which amounts to seventeen dollars above mentioned, and by accepting this deed said Dr. John Cooke released said claim.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this 25th day of March 1881

Anna E. Jones

The signing and sealing of the above was witnessed by the undersigned at the request of said Anna E. Jones

W.W. Conoway

J.E. MacDonalds

State of Ohio, Belmont County ss: before me, F.C. Robinson, a Notary Public and for said county, personally appeared the above named Anna Eliza Jones and acknowledge the signing of sealing of the above instrument to be her voluntary act and deed, this 25th day of March 1881.

T.C. Robinson, Notary Public.

It was now late in the evening of Friday, and having all things in readiness, she presented the Dr. with his “deed,” receiving therefor his receipt in full for his bill, and the old woman mounted the hill by the aid of a lantern “to deliver the goods.”

Reaching Boggs’, she called for writing materials, wrote a letter to a Mrs. Berry, in Martin’s Ferry, saying among other things, that “ere that reached her the writer would be dead,” &c., Giving this to Agnes, with orders to mail it, she kissed the baby, called for the keys of the door, which at first were refused her, but then given her, she took a chair in hand and mounted it beside a post in the yard to which was fastened a clothes line—fastened one end of the rope around her neck, the other to the post, and pushed her old bark off, into the darkness and eternity. She informed Boggs & Co., that she meant to hang herself—but, as he alleges, she had threatened to destroy herself with pistols and by starvation before, he paid no serious attention to it. When morning came, however, Boggs & Co. saw the old woman hanging by the neck dead. The alarm was given, Coroner Garrett summoned, and after hearing the facts as related, he decided Anna E. Jones came to her death by her own hand, and of premeditation. The goods were delivered. The old woman was a good as her word. Setting a wholesome example to many creditors, to either “pay up” or “go and do likewise.” We can but revere the old woman’s memory for her determined purpose to pay an honest Dr. bill. Oh! That others we know of would profit by the old woman’s example—pay their bills we mean—or—or—well, a “word to the wise is sufficient.” Dr. Cooke waived all present claim to the old woman: her body was taken in charge by the Township Trustees, and by them buried on Sabbath afternoon, at Bridgeport Cemetery. A solitary vehicle alone formed the funeral cortege, with not a mourner to drop a tear for the strange determined old suicide.

As they rattled her bones over the stones,

The old dead woman that Dr. Cooke owns.

Belmont Chronicle [St. Clairsville, OH] 31 March 1881: p. 3

The rhyme at the end comes from a much-quoted poem called “The Pauper’s Drive” attributed to Thomas Hood. It has the refrain

Rattle his bones over the stones

He’s only a pauper whom nobody owns.

Ohio was home to some of the giants among bodysnatchers. Yet even the “Prince of Ghouls,” probably knowing that his body would be stolen anyway, decided to profit from it when alive.

The man about whom more graveyard stories have been told than about any other “resurrectionist,” was “Old Cunny,” the prince of ghouls, who in his day was known to every person in this part of the country, at least by name. He was the bogyman for all ill-behaved children. He was popularly called “Old Man Dead.” His real name was William Cunningham. He was born in Ireland in 1807. He was a big, raw-boned individual, with muscles like Hercules, and a protruding lower jaw, a ghoul by vocation, a drunkard by habit and a coward by nature. His wife was a bony, brawny, square-jawed Irish woman, with a mouth like an alligator. Both had a tremendous appetite for whiskey. Cunny had sold his own body to the Medical College of Ohio. When he died of heart trouble in 1871, the body was turned over to the college. Mrs. Cunningham, the bereaved widow, managed to get an additional $5 bill for the giant carcass of her deceased spouse. The skeleton of “Old Cunny” is to this day the piece de resistance in the Museum of the Medical College of Ohio. Daniel Drake and His Followers, Otto Juettner (Cincinnati, OH: Harvey Publishing Company, 1909): p. 395

Cunningham’s apprentice and eventual partner followed Old Man Dead’s example.

PICKLED

CHARLEY KENTON, THE RESURRECTIONIST,

GOES BACK ON THE PROFESSION

HE SELLS HIS OWN BODY TO THE DOCTORS

AND IS CARRIED FROM THE DEATH-BED TO THE PICKLING VAT

Last Friday night a coffin containing the dead body of a colored man was driven to the Ohio Medical College, taken from the wagon and carried up the stairs, with little, if any, effort at concealment. Arriving in the “dead-room” the body was taken from the coffin, the large artery in the side of the neck cut, the blood removed, and the arteries filled with a preservative fluid, after which the body, divested of its clothing, was tumbled, with no further ceremony, into the “pickling tub,” along with a couple of dozen others which had been quietly accumulating during the past month. There was a peculiar lack of the secrecy which accompanies most of the operations of this sort by which dead bodies are transferred to the dead-room of the college, and a business-like air about the whole transaction which indicated that it was somewhat different from the ordinary cases of grave-robbing and body-snatching. A little inquiry into the case showed that it was a peculiar one—that, in fact, the body was that of one of the most notorious body-snatchers of the city, and that the lack of secrecy in the matter was from the fact that it was merely the carrying out of a plain business transaction, that the dead man had in his life sold his body to the college for dissection after death, receiving the payment, and that in accordance with this agreement his body was thus being removed to the dissecting room for that purpose.

Charley Keaton, the dead man, was in his life one of the most active body-snatchers in this city, and from his hands have hundreds of “stiffs”—bodies from many of the burying grounds in the city and vicinity, somebody’s loved ones to whose memory tears have fallen and marble shafts aspired heavenward—been sent down through the terrible “chute,” and upward through the death shaft to the dissecting room.

Keaton was a colored man of about forty, and had been for more than ten years in the business of body snatching, making good money at it, and coming to rather enjoy it than otherwise. To him there was nothing more in the handling of stiffs than in so many bolts of cloth or sacks of grain, and no more in dissection than in the business of the butcher or meat vender.

He began his work with “Old Cunny,” the noted resurrectionist, and followed it through all seasons and all weather, until only a few weeks before his death. In it he encountered all sorts of weather and exposures, and so contracted colds and a cough which finally led to bleeding of the lungs, and so his life among the dead ended in death, whose presence was as familiar to him as the days of his years of manhood.

To him the medical college, the chute, the dead-room, the pickling-vault, and even dissection had no horrors; familiarity with these had deprived him of that feeling of repugnance so common to mankind, and especially to his race, and as a result he had expressed a willingness in life that his remains after death should be submitted to the dissecting knife “in the interest of science,” as he said, as he considered his business and that which he supplied, inseparably interwoven with the science of anatomy and medicine, and as a result he had sold—deliberately sold during his life-time–his body to the college professors, receiving the usual price, $35 cash in hand, and giving a receipt and statement that his body should become the property of the college after dissection.

Indeed, he seemed rather to prefer that his skeleton should stand beside that of old “Cunny” in the museum of the college than to mold to nothingness in the dark, damp earth, and in life he frequently contemplated Cunny’s skeleton as it stands, spade in hand, in the college, evidently reflecting that he would someday stand beside it, and keep the “ole man” company through the many years that the college shall stand, instead of being consigned to the changes and final nothingness of the Potter’s field grave.

So when old Charley died on Friday last, the college authorities were notified, his wife, who had accompanied him on many of his nightly expeditions, and is herself an expert anatomist, prepared the body for dissection, and after the brief funeral service, it was removed from the house on Barr Street, where he lived and whence he had sallied forth for many nightly excursions in the homes of the dead, and taken directly to the college, where it was prepared and put in pickle. It is pronounced “excellent material,” being well developed and obtained without serious delay after death.

Whether this is strictly “professional,” as viewed from a body-snatcher’s stand-point, seems extremely doubtful. A system which takes the body with the consent of all parties concerned direct from the death-bed to the dissecting-room, and upon an agreed-upon and already paid price, seems to be one which must undermine the business of the profession, and therefore should be frowned down by every patriotic body-snatcher. Hawarden [IA] Independent 14 August 1878: p. 2

I’ve asked the librarians and archivists at the University of Cincinnati School of Medicine (the successor to the Medical College of Ohio) if Cunningham and Kenton’s mounted skeletons are still in their collection, but no one seems to know. If you have any answers, sack ‘em up and send to Chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com.

Mrs Daffodil posted about a unique method of Burking by Snuff, the other day. Look for similar joy and jollity in The Victorian Book of the Dead, which can be purchased at Amazon and other online retailers. (Or ask your local bookstore or library to order it.) It is also available in a Kindle edition.

See this link for an introduction to this collection about the popular culture of Victorian mourning, featuring primary-source materials about corpses, crypts, crape, and much more.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.