Silk Hats and Quicksilver: A Prussian Execution

Silk Hats and Quicksilver: A Prussian Execution The Prussian Death Machine

As the debate goes on in various states about the appropriate way to administer capital punishment, a call has gone out from Saudi Arabia (on its civil service jobs portal) for eight new executioners to carry out public beheadings. Since I have been dwelling on arcane methods of execution far more than is good for me, a brief rummage in the files found this “improved” method of beheading, “in vogue” in 1901 Prussia.

One of Butte’s Doctors Describes a Prussian Execution.

The question of capital punishment as the extreme penalty for the most heinous of crimes has long been before the English-speaking world for solution and, though it has occupied the attention of the pulpit, the press and the lawmakers generally, there is no unanimity of opinion regarding it. That is particularly the case in the United States. In many states capital punishment is not inflicted, the extreme penalty being imprisonment for life. In some states men are hanged, sometimes dropped through the trap of a scaffold, other times jerked from the ground; in other states the death sentence is carried out with electricity as the death-dealing agent, and in still other states the condemned may choose between being hanged or shot. All of which goes to show that, though the question of how to deal out the extreme penalty has been argued pro and con in various localities under the jurisdiction of our stars and stripes, there is not only a difference of opinion s to the best and most humane methods of executing a criminal, but there are varied opinions.

Most English-speaking people of today look back with horror upon the garrote; they think the guillotine a butcher’s machine and they regard the block as a relic of barbarism. Yet they hang a man, electrocute him or shoot him, and the respective advocates of the methods employed in the United States think the hanging, the electrocution or the shooting, as the case might be, to be the best manner of executing. The same condition of affairs exists in Europe, only the difference of opinion there are concerned in hanging, garroting and guillotining, and, though it is not generally known, beheading at the block. The garrote is in used in Spain. It can be safely said that of all the methods of execution it is the most horrible, and notwithstanding that fact, it was used recently in the execution of a man in the Philippines, and that execution was conducted under American supervision. The hangman still does business in England, and in France the guillotine is the death-dealing agent.

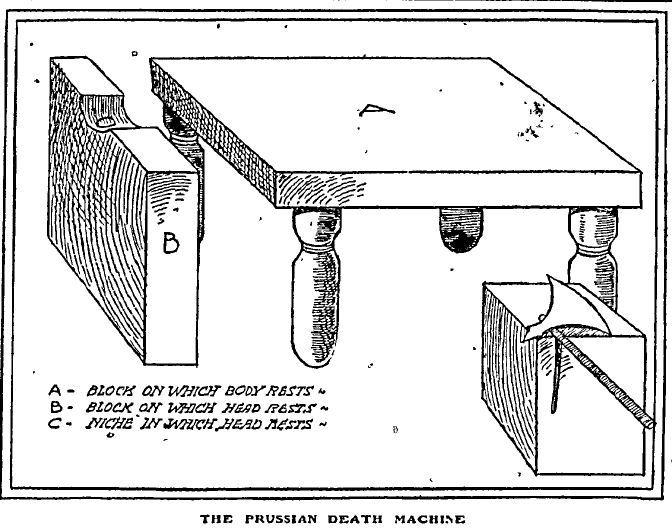

In Prussia the block and the axe are still in use and, according to Dr. Herman Westphal of Butte, recently the chief of staff of the city hospital of Baltimore, Md., that method of execution is the best; the most horrible, he admits, for the condemned, but, at the same time, the most humane for any person who must lose life. There are not many who know that the headsman still officiates. He is not the headsman of old, an awe-inspiring individual in doublet and a mask, but a gentlemanly-appearing person, dressed in black frock and silk hat, and who wears no covering to hide his identity. His axe is not of the same pattern which separated Charles I from his head in the Tower of London on that fateful 30th of January, 252 years ago, nor is his block the same as that on which the head of Mary, Queen of Scots, rested when the axe ended her career. The axe of today in Prussia is short handled and is swung with one hand, and the blocks—for there are two of them used in a beheading—consist of a long “body” block, on which the condemned is stretch out at full length and face down, and a short “head” block, just a few inches removed from the “body” block. The “head” block is higher than the “body” block, so that the body is in an inclined position, with considerable of the weight of the body being supported by the head. The instant the head is severed the upper part of the body drops on a level with the lower part and the blood that spurts from the carotids, instead of gushing all over everything about, strikes against the face of the “head” block, and there is no disgusting scene. Little or no blood is seen at all…

“The knife as used in the guillotine is all right,” says Dr. Westphal. “It does sure work, does it quickly and humanely, but that is not all there is to an execution. The man to be executed is to be considered. The taking of his life should be done in the manner which will be least painful to him, not only physically, but mentally. And there is where we find an objection to the guillotine. The great engine of death strikes as much terror to the heart of the man who must approach it to meet death as does the scaffold. With block and axe, the condemned see no great instrument in front of him as he walks to his death, and before he knows what is taking place he is on the block and his head is off. Hanging, I think, is a terrible method of death, shooting I could never advocate, and electrocution is horrible, not only for the victim, but for the witnesses. What makes it most horrible is that the agent of death is invisible. You see the victim strapped in a chair and the next instant you see him struggle and wiggle; you hear the straps strain and oftentimes you smell burning hair and even flesh, and yet you cannot see the cause for it. A man may not be killed instantly, but continue to have life for several minutes, as is the case in hanging, and at a hanging I have been able to detect a pulse 15 minutes after the drop fell. To my mind the method of execution in vogue in Prussia is the best I have ever seen.”

The execution in Prussia referred to by Dr. Westphal was that of a sheepherder, whose name was Franz Deppe. He was sentenced to death, after having been convicted of the outraging and murdering of a 7-year-old girl. The place of the execution was in the courtyard of a prison at Flensburg, in Schlewsig-Holstein, near the Danish frontier. The story given in part as follows is interesting:

“In the first place,” says Dr. Westphal. “I was particularly fortunate to get an invitation to the execution. I secured it through the efforts of a personal friend, who was kreisartz, or district physician or surgeon. The invitations are limited and great care is exercised in giving them, and particular about keeping the hour of the execution a secret with the invited guests and the prison officials. The invitation, when translated, reads as follows:

CARD OF ADMISSION

To the Yard of the District Prison

Friday, July 5, 1901

6 a. m. sharp.

Dr. H. Westphal.

The First State’s Attorney pro tem.

SCHROEDER

Flensburg, July 2, 1901

Accompanying the card of invitation was a note from the kreisartz, through whom it was obtained, admonishing Dr. Westphal to secrecy and prescribing the garb to be worn. The note was as follows:

“My Dear H. Inclosed I send you card of admission for the execution. You must under no circumstances speak about this, as the time of execution must be kept secret. Dress, black frock coat and high hat. Yours.

“VON F.”

“It was just 10 minutes before 6 o’clock when I arrived at the prison,” continued Dr. Westphal. “Everything was in readiness and the few favored witnesses, all attired in frock coats and silk hats, were already assembled. The headsman, similarly attired, was standing between the blocks and a small table on which I saw a white cloth covering the executioner’s broad axe.

The actual execution is the topic I would rather speak of. When the big prison clock struck 6, Deppe, with guards on either side of him, had passed through the great doors form the prison into the courtyard. He was at the doors at the second stroke of the clock. Before the sound of the sixth stroke had died away the first state’s attorney had read the affirmation of the death warrant and was asking Deppe if he had any confession to make. Deppe replied negatively and glared at the attorney. Then the attorney indicated the signature of the Kaiser Wilhelm and said to Deppe: ‘You see what the emperor has done?’ It appeared that Wilhelm had been appealed to to commute the sentence and had refused to interfere.

“After Deppe had glanced cursorily at the signature the state’s attorney said, addressing the headsman: ‘Do your duty.’ The next instant the guard seized Deppe and the assistant of the headsman grasped the man by the hair of his head. In a jiffy Deppe was prostrate face down on the body block, and the next instant the assistant had pulled the head onto the head block. There was no word; everything was understood. There was a whisk and the headsman stood with the white cloth in his left hand while the right hand gasped the handle of the axe lying on the table and which had been covered by the white cloth. The grasping of the axe and its swift descent appeared to have been accomplished by one move. There was no sound as the keen blade severed the head and there was absolutely no struggle. A man could not die more quickly than did Deppe.

“Before the axe had been replaced on the table the assistant had lowered the head out of sight. There was nothing disgusting; scarcely any blood was to be seen. I marveled at it until later I found a zinc kettle in the space between the ‘head’ and ‘body’ blocks. What was its purpose can readily be guessed. Within a few minutes the body of Deppe had been placed in a coffin already directed to a medical college and the head was placed with it. The coffin was then closed and borne away. Even then I could scarcely realize that it was all over. It had been so clean and well done that I could not bring myself to believe the law had taken a human life. I was brought to my senses when an attendant appeared with a bowl of steaming water and approached the headsman. The latter dipped his finger tips in the water as one would use a finger bowl at table, wiped his fingers with a napkin, smiled and bowed and left us. You would imagine from the bow that he was bidding some hostess adieu after having accepted her hospitality at some very formal function.

“After the execution I learned that the executioner was known as Herr Reindell and that he traveled about the country serving wherever his services were needed. I was also told that he received 200 marks, or about $50 for each execution. I asked one of the principal officials about the chances of the axe not severing the head and he replied that it was a certainty here would be no such accident. He explained that the keen-edged blade and its handle were hollow and that the hollow space was partly filled with quicksilver. This metal flowing into the blade on the downward stroke added to its weight and assisted in driving through flesh and bone.

“Judging from my own observation,” said Dr. Westphal in conclusion. “I should say that in all the years that have elapsed since beheading went out of fashion in other part of Europe, we have not been able to produce a substitute which is at one and the same time so terrifying and so merciful to the condemned as the chopping block. It is better than hanging, more certain even than electricity. It has also that quality of horror, which serves better than any other method ever devised, except perhaps the rack, to hold the criminally inclined within bounds.”

Anaconda [MT] Standard 8 May 1904: p.

A few years before this story appeared, this notice, advertising an upcoming vacancy appeared. The mention of “hangman” in connection with Reindell is a misnomer–hanging was not used in Germany until the Nazis came to power.

In spite of the odium which is supposed to be attached to the office of the hangman in Europe, there is a great rush for the position of high executioner of Prussia, now that Herr [Friedrich] Reindell, the present incumbent, is about to retire. The post pays $37 “a head” and travelling expenses.

The Green Bag, An Entertaining Magazine for Lawyers, Horace W. Fuller, editor, 1897

This article, about the Reindel family executioners says that Reindel retired in 1898 and that his son Wilhelm was dismissed for incompetence in 1901. Dr. Westphal’s invitation reads “1901.” Did Friedrich Reindel come out of retirement for this occasion?

When did this execution method get the chop? I can’t speak for Prussia, but in Germany, apparently the last axe execution took place in 1935–of two women, although it is possible beheadings continued during the Second World War. See this post from Dr Beachcombing on the controversy.

If you are interested in the history of executions/execution methods, see the “Crime” category for more on this grim and grewsome subject.

Thanks to Fredric D. for writing in with some corrections on the subject of this post. Many thanks, Frederic!

Dr. Westphal’s description is accurate with these exceptions:

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.