Snapped for Eternity: The Victorian Mummy Portrait Fad

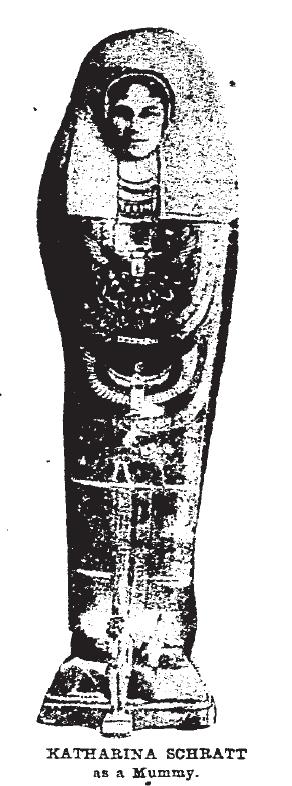

Snapped for Eternity: The Victorian Mummy Portrait Fad Katharina Schratt photographed in a mummy case, c. 1904

I am always interested in the ephemeral—the fashionable fads and enthusiasms that had their 15 minutes of fame in, say, 1871. Today we look at a photographic fad which left surprisingly few physical artifacts.

Even before the discovery in 1922 of King Tut’s tomb sent the world mummy-mad, there was Description de l’Égypte by Napoleon’s tame scholars, Admiral Nelson and the Battle of the Nile, connoisseur Thomas Hope’s popular Egyptian gallery, and winter tours of Egypt undertaken by the fashionable. Essential elements of these tours were sailing a luxury dhow down the Nile, the Great Pyramids by moonlight, tea at Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo, and exotic souvenirs ranging from an Egyptian princess’s desiccated hand (complete with curse) to a personal “mummy portrait.”

Around 1898, the first stories of the new fad appear:

MUMMY PICTURES

The Latest Fad in Photography For Society Women

Society often goes out of its way to obtain a fresh sensation. The latest craze, which was inaugurated by Mrs. James P. Kernochan of New York on her return from abroad, is to pose for one’s photograph in a mummy frame. This startling fancy originated in Cairo, Egypt, in which place Mrs. Kernochan spent last winter.

To obtain a mummy case in Cairo is a comparatively easy matter. The enterprising photographer there keeps one in stock for his American patrons. The picture is taken in this way: The subject steps into the case, which is placed on end, and the lid is then closed, leaving an opening just large enough for the face. [Apparently the idea of cutting a hole in an archaeological artifact for a joke photograph does not seem to have horrified any of the papers circulating this article about Mrs.Kernochan.]

It is a grewsome idea, but a popular one. The mummy pictures are considered graceful and appropriate souvenirs of a trip to Egypt to present on returning to the friends at home.

The fad has attained such instant popularity, however, that many persons are not waiting for a tour of the east in order to see a picture of their own faces peering out at them from a mummy case. New York photographers prepare a picture of a mummy case and simply insert the face of the person desirous of obtaining such a unique photograph.

It is whispered that a number of these weird photographs are to circulate on All Halloween, when the ghostly and the ghastly are always in demand. The girls are already finding amusement in replying to requests from amorous swains for their photographs by presenting them with a mummy picture. Bets and philopenas** are also canceled in this fashion. The feelings of the lover may be imagined when he is unexpectedly confronted with the features of his beloved enshrouded in the antique habiliments of death.

Many people think that the idea is too morbid to be encouraged. The mummy case is too suggestive of a coffin to be entirely pleasant. However, this weird fancy is desirable at present, and for its little day the mummy picture promises to be a popular fad. New York World. Kalamazoo [MI] Gazette 1 October 1898: p. 7

**Philopenas? I had no idea. Here’s the definition:

A game in which a person, on finding a double-kernelled almond or nut, may offer the second kernel to another person and demand a playful forfeit from that person to be paid on their next meeting. The forfeit may simply be to exchange the greeting “Good-day, Philopena” or it may be more elaborate. Philopenas were often played as a form of flirtation.

Given this link with flirtation, possibly there was some trace of the impulse that makes teenaged girls want to dress as sexy vampires or zombies. Give the young man a jolt of adrenaline and he will think his heart is racing because of you.

Another article, with no illustration, says that in Paris photographs were taken with the subject bandaged like a mummy and lying down in the sarcophagus. Charleston [SC] News and Courier 14 March 1899: p. 4

Mummy portraits saw a revival of press interest in the early 1900s. The photograph at the head of this article comes from a 1904 article about Katharina Schratt, who was reputed to be the mistress and/or morganatic wife of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria [Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 25 July 1904: p. 4]

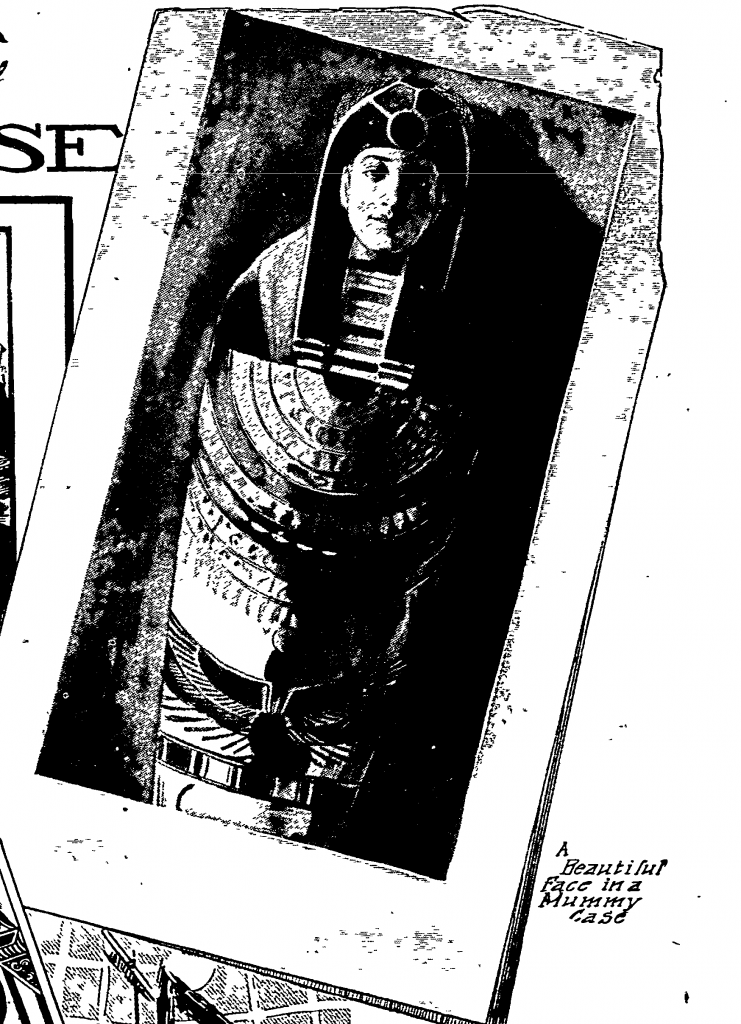

Snapped for Eternity: The Victorian Mummy Portrait Fad . A mummy portrait From the Philadelphia [PA] Inquirer 3 May 1908: p. 1

A PRETTY FACE IN A MUMMY CASE

His best girl’s face peering from the depths of an ancient mummy case is the sight which is liable to startle the fellow who is not forewarned by the article. It is the latest fad which has struck London, the fountain head of many fads and foibles, especially those of the fair sex. The photograph is not gruesome as one might suspect at first thought, but on the other hand, the coarse lines of the mummy case and the crude hieroglyphics thereon, serve to accentuate the pretty lines of the girl’s face.

Some of these pictures have been brought back by members of the smart set who have been abroad for the winter.

The idea originated with a London photographer who had made a trip to ancient Egypt with a scientific expedition, and while there, he decided to make a portrait of the pretty face of the daughter of one of the members of the expedition. She is a lovely creature who had accompanied her father, one of the leading Egyptologists of the world. In order that the picture might be a souvenir of the occasion, he conceived the idea of placing her sparkling eyes and rosy cheeks in a mummy setting.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER’S TRICK

This was a comparatively easy trick for a photographer. He made a large picture of a mummy and then a picture of the lady. Cutting out the face he neatly pasted it over that of the mummy. The result was startling and perplexing and upon exhibiting the picture on his return to London he found that he had made a great hit. He was besought on every hand by fashionable women to duplicate the picture. Soon it was necessary to set up a studio especially fitted out for this kind of work. The artist made use of some oriental material which he had brought back with him from his trip, and had several mummy cases made to suit his demands by a Parisian who had achieved a world reputation for forging ancient pottery, carvings and other things which have been uncovered by the investigators in the buried cities of the Far East.

The Frenchman entered into the spirit of the occasion and turned out some mummy shells which defy detection. This is only a front, behind which the model stands with her face to an opening corresponding to that once occupied by the mummy. The surroundings are so harmonious that the photograph, when finished, has the appearance of one which was taken in the tomb of some dusty and long-departed queen of the Nile country. Philadelphia [PA] Inquirer 3 May 1908: p. 1

When it comes right down to it, this fad was merely a more elevated, historic version of carnival cut-out pictures where people peer through the faces of the sailor and the mermaid. For the budget-conscious, if the genuine article was not available, “realistic” cardboard coffins or sphinxes could be substituted, although I have to say, they simply scream provincial-opera-company Aida stage prop. You can see a photograph of some silly examples here in a 1908 issue of Popular Mechanics. Were the subjects’ faces made up for the photograph to resemble stone or metal?

I wondered if there was any particular explanation for an interest in mummy portraits—other than the standard Imperial Victorian fascination with the exotic. Two possibilities suggested themselves:

1) The discovery of the Fayum mummy portraits (c. 1880s-1910s) by men such as Daniel Marie Fouquet and Flinders Petrie created a sensation. Reporters describing the portraits rather rhapsodized, both about the modernity of the style and the beauty of some of the female subjects.

“as near and akin as if they had been painted by Copley or Stuart in the last century, or by Hunt 15 years ago, or by Sargent or Tarbell yesterday. There is, in particular, the portrait of one brilliant and beautiful girl that looks as if the original might have stepped out of a Boston Symphony rehearsal last Friday afternoon.” [Boston [MA] Herald 10 November 1893: p. 8]

Note the mention of fashionable portraitists of several eras. What society woman wouldn’t want to be like those exotic ladies?

2) Around 1908 the stories of the “cursed mummy case” of the Priestess of Amen-Ra in the British Museum began to be widely circulated. (Another post, another day.) One feature of the legend was that photographers of the case would find a mysterious malign face on their photographs and, of course, would either die or have a bad accident. The idea of photographing a mummy’s face gave an additional frisson to the curse stories and may have given impetus to the second wave of interest in mummy portraits.

The mummy portrait fad seems to have lasted until around 1910. I found only three illustrations in the papers and this example in a recent article on Victorian-era novelty photos. I’ve looked at auction sites and online, but have come up empty-handed. Why do so few of these images survive? Did the papers exaggerate the extent of the fad? Were they comparatively rare to begin with since they were not to everyone’s taste and not everyone could travel abroad? (The articles make it plain that identical photos could be had in London and, I would expect, other metropolitan areas.) Did later generations find the photographs morbid and destroy them? (Unlikely, given the large quantities of genuine post-mortem photographs that survive from the era, which, to the modern mind, seem even more morbid.) Or did the friends at home, the recipients of those “graceful and appropriate souvenirs of a trip to Egypt” quietly tip them in the bin with the wrapping paper? Until I find definitive evidence, I’m inclined to the latter view.

Can anyone supply a link to a 19th– or early-20th-century photographic mummy case portrait?

For more on the subject: Egyptomania; Egypt in Western Art; 1730-1930, Jean-Marcel Humbert, Michael Pantazzi and Christiane Ziegler, 1994

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.

Mrs Daffodil has more on the subject in “A Pretty Face in a Mummy Case.”