The Electric Sea Serpent

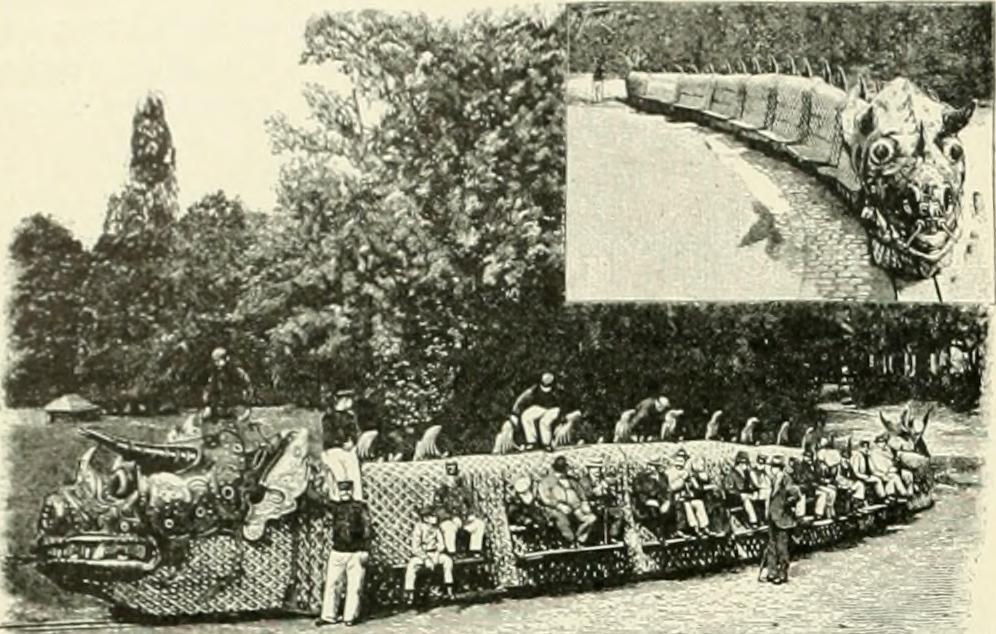

The electric sea serpent showing riders along its sides.

Tomorrow is Sea Serpent Day, while today we commemorate the birthday of Charles Hoy Fort. Last year, on his natal day, we raised a tin box of precipitated froglets in Danville, Virginia; today we fête Mr. Fort with a ride on the Electric Sea Serpent!

Of course, you have read from time to time more or less startling accounts of the sudden appearance in different parts of the world of our and respected friend the sea serpent, but probably you never expected to find one included among the occupants of a well-known Zoo. What, then, must have been the feelings of the ophiologists, naturalists, and savants of France when, to their surprise and astonishment, Le Chenil, the official journal of the Jardin Zoologique d’Acclimatation, Paris, calmly announced in its columns that the fabulous marine monster had arrived, and was receiving visitors at the Jardin daily? What the animals thought about their new comrade is best told by giving a translated extract from the journal referred to.

It says, “The poor beasts who were present when the frightful monster arrived appeared petrified with fear; even the biggest amongst them, the elephant, was stupefied to see an animal more than a dozen times as large as himself. The camel and the giraffe opened wide their eyes in consternation, and trembled on their feet. The monkeys made the most horrible grimaces, and made use of what sounded like dreadful language, which I am sorry to say was repeated by the parrots and cockatoos, who really ought to have known better. Even the crocodiles aroused themselves from their habitual torpor and waddled out of their ponds to see if the rumour which had reached them was true.

“Among all the occupants of the Jardin, the only ones not frightened were the cranes; snakes are their natural food, and as they perceived the sea serpent coming in their direction they opened their great beaks to the widest extent, in anticipation of a satisfactory meal. When, however, it arrived quite close, and they saw that this ‘tit-bit’ was nearly the size of the Vendôme Column, their chagrin was intense. Realising that this snake was really too large even for them to swallow, they uttered cries of anguish and let fall their-wings (I had nearly said arms) in impotent rage.”

At the risk of being warned against the awful results of intemperance, we ask you to imagine a huge body writhing along, thirty yards in length, covered with greenish skin and bright metallic scales and spines. A most ferocious-looking head, a mouth large enough to swallow a boat-load of Jonahs, furnished with vicious teeth and a forked tongue as long as your arm, horns as thick as the trunk of a tree, and glaring eyeballs the size of wash-stand basins.

Notwithstanding that this extraordinary beast for the first time in public during the Paris Exposition of 1900, it is the creation of one of our own countrymen, the inventor being Mr. Walter Stenning, who hails appropriately enough from a seaside resort, Brighton, and has spent more than half his lifetime exploiting and producing novelties and attractions at shows and exhibitions at home and abroad. The invention is patented in various countries, and is now the property of the Sea Serpent Syndicate, Limited, of which company Mr. Stenning is the managing director. For the benefit of those who are anxious to know “how it is done,” we give the following particulars:—

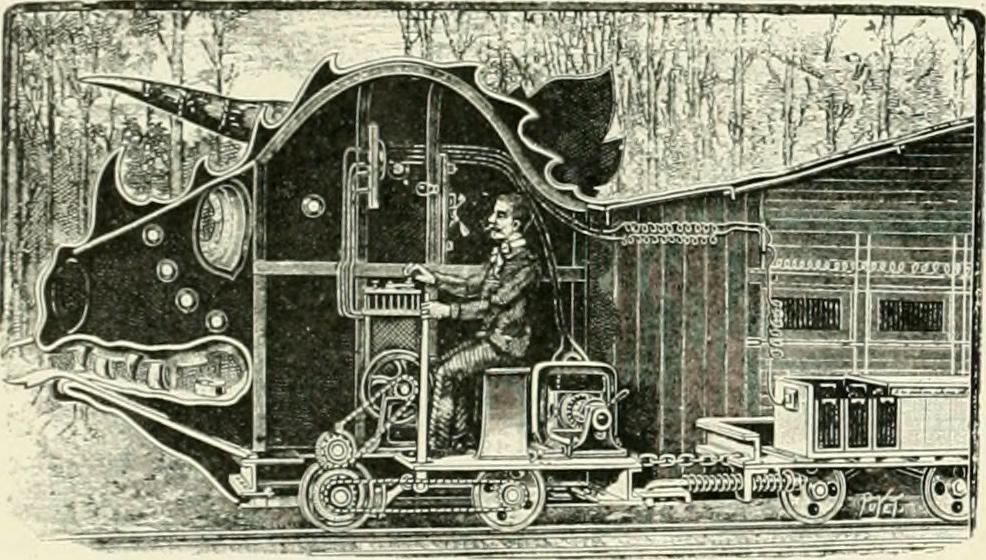

First, the serpent is amphibious, and is equally at home on land or on water. In | reality it is a small train concealed by a continuous cover or carapace. This train runs upon a sinuous track of iron rails laid either upon the ground or submerged a few inches under the water.

The skeleton of the serpent is formed of eleven small waggons fitted with an iron framework forming the ribs. Each car is covered with a wooden shell and connected with the adjoining cars by means of an accordion-like bellows, which expands and contracts, permitting the train to travel round sharp curves.

The total length of the body is ninety feet, covered with prepared canvas from end to end, and encrusted with some eight thousand diamond-shaped brass, copper, and nickel scales, To enhance the effect these scales are outlined in colours; this entailed a great deal of work, as the artist who undertook the task found to his cost.

He began quite blithely, but when he had painted 3,000 scales he began to find it monotonous; however, he struggled on to the fifth thousand, and then begged to be excused from doing the remainder, as his mind was becoming affected, and he could think and dream of nothing else; besides which his wife objected to him getting up in his sleep and painting imaginary scales with a shaving brush.

The head, tail, and spines are beaten out of sheet brass and copper, more than one ton of these metals being used in their construction.

This portion of the work was executed by the well-known theatrical armourer, M. Tachaux, of Paris, from designs supplied by the inventor, and occupied M. Tachaux and his three assistants nearly six months to complete.

It is all handwork, and as a specimen of artistic coppersmithing is unique.

In connection with the design of the head, Mr. Stenning relates a somewhat remarkable coincidence. In order to avoid technical difficulties of construction, he took his plans of the iron framework to M. Tachaux’s studio, and there made the sketches for the head and tail as now seen. This was in January 1900.

Some time after the head had been completed, Mr. Stenning visited the Palais d’Optique in the Paris Exhibition, where, among other scientific wonders, was shown a series of tableaux representing the Earth before Man. One of these tableaux consisted of models of gigantic antediluvians labelled “Serpents de Mer,” and, strange to say, one model was identical with that designed by himself. It is certainly a curious thing that the model, which was the work of well-known scientists, and reconstructed from geological discoveries should bear such a strong resemblance to that drawn from pure imagination.

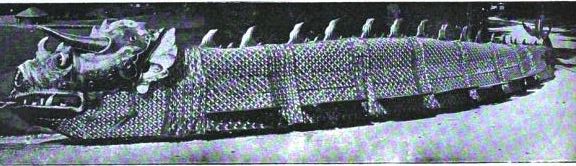

Looking at the photograph of the sea serpent without any passengers, the seats are invisible; as a matter of fact, they are folded back into the body when not in use.

Each car has six seats, and the three middle cars are identical; this allows of a surgical operation being performed. For instance, it might be found necessary to reduce the length of the serpent owing to lack of space. In that case the serpent would be cut in half, one, two, or three cars removed, and the two ends joined again without in any way interfering with the health or working of the monster.

The cars also contain the electrical accumulators which supply the energy to the two motors, one of which is situated in the middle of the body and the other in the head.

The head also contains the starting and stopping apparatus, and the driver sees through the nostrils and listens through the ears, which, by the way, measure five feet from lobe to point. In the photograph below the driver’s face can be seen in the ear-hole.

Perhaps the most striking features are the eyes, which can be illuminated at night. They are 42 inches in circumference, and are probably the largest pair of artificial glass eyes ever manufactured.

The sea serpent can hardly be called “a light weight,” for he turns the scale at eleven tons without passengers.

The speed at which he travels can be varied from three to seven miles an hour.

After the perusal of this article and inspection of the accompanying photographs, no doubt many of our readers will want to make a closer acquaintance with such an interesting curiosity, therefore it will please them to hear that there is every likelihood of their desire being gratified, for the sea serpent is coming to Earl’s Court, London.

The Harmsworth London Magazine, Vol. 6, February 1901

Cross-section of the electric sea serpent

In 1891 The Street Railway Review reported on the attraction with a little joke at the expense of the French.

ELECTRIC SEA SERPENT FOR PLEASURE RESORTS

The illustrations herewith show Mr. Walter Stenning’s idea of the sea serpent which sundry and divers travelers have reported having seen at different times since 1555. It was built in Paris and during the past summer has been one of the attractions of the Jardin d’Acclimation. Our French contemporary, La Nature, says concerning the sea serpent: “The visitors to the Jardin d’Acclimation arrest themselves stupefied when they perceive circulating softly in the alleys, through the foliage, this rolling monster.”

And we do not blame them.

The serpent is about 100 ft. long and 6 ½ ft. in diameter; it consists of an electric locomotive drawing a train of cars carrying the necessary storage batteries to furnish current. Each car is covered with a ring of the animal’s body. The Street Railway Review, Vol. X, No. 12, 1891 p. 738

The much long version and description, in French, in La Nature, may be found here.

Anyone else see a resemblance to Binkley’s anxiety closet Monster in Bloom County?

For more illustrations see this link.

Happy Birthday, Mr. Fort!

Mrs Daffodil is celebrating Sea Serpent Day with a striking illustration.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.