The Silver Coffin of Genghis Khan

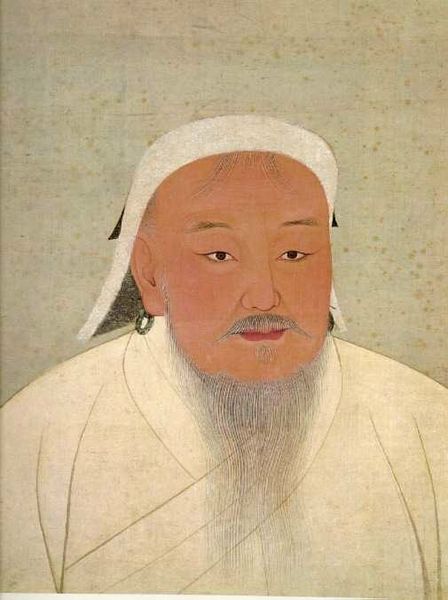

The Silver Coffin of Genghis Khan. A portrait of Genghis Khan, created under the direction of his grandson, Kublai Khan. National Palace Museum, Taipei

It is on this day in 1227 that Genghis Khan is said to have died during the battle for Yinchuan, perhaps of an infected arrow wound. He had asked to be returned to his birthplace for burial and like Alaric and Attila, he was buried in a secret location with those who entombed him slaughtered to keep the secret. Many people have searched for the tomb of the Khan down the centuries, and there are some recent, crowd-sourced efforts using satellite images, which show promise. It should be noted that those who revere his memory do not want it found and some believe he would not want it desecrated. But, lo! in 1927, the papers were buzzing with the news that the long-lost tomb of the Great Khan was found again.

Stirring the Ghost of Genghis Khan

Has the Tomb of the Famous Mongolian Conqueror Been Found on the Gobi Desert After Seven Centuries of Guarded Sleep?

At Least the Fantastical Legendary Tales Have Endured Through the Years.

Black night blows across the dread Gobi Desert. Darkness catches like a very veil on the mountains that rise sepulchrally on China’s vast salt-incrusted waste of sand. Strange points of light, seeming to come from nowhere, only add to the mysticism that fills the dark mountainside. A traveler on the tundra would draw his coat about him and huddle closer to his camel. But travelers are few on these wild, desolate ridges of sand.

Suddenly a blur of light obscures all previous impressions. A figure rises up out of the black. One by one the lights are extinguished. There is a groaning as of men at fanatical prayer. Minutes pass. All is still.

Once a year it is said on the anniversary of the great Genghis Khan’s death, his ghost rises form his kingly tomb and blows out the lamps which have guarded it these 700 years. He leads the chief of the lamas to the huge black slab at the rear of the shrine and writes with the priest’s hand the prophecies for the coming year.

This is a ghost story centuries old, but told only in the year 1927. It is related in connection with the reported discovery of the tomb of the famous Mongolian conqueror by Prof. Peter K. Kozloff, Russian archaeologist and traveler, who has caused a furor all over the world by announcing that after twenty years of search he has come upon the hidden burial place of the Khan, who first conquered and then ruled half the world.

If the discovery of the tomb proves authentic, its importance would rank with the finding of the tomb of Tutenkhamun, but the story of the coming upon this hidden house of death in a mountainside relates of treasure so fabulous and of legend so strange that many are inclined to be skeptical. They believe that perhaps the report is a mistaken one and the great desert of the Gobi sleeps on as before, holding in its fastnesses the secret that has for seven centuries defied mankind.

Has the tomb of Genghis Khan been found? In that labyrinthian passage cut into the mountainside did the patient scientist stumble upon the jewel-studded weapons of “the Emperor of All Men” and his silver coffin resting upon the crowns of the seventy-eight Princes and Khans whom he had conquered?

Or does the waste of Gobi still hold its secret inviolate and is this a riddle the answer to which is to be denied to men forever? Busy modern men have developed a strange passion for the burial places of ancient kings. When Lord Carnarvon discovered and opened the tomb of Egypt’s great ruler he brought about events that rocked the world.

In the grave of the Mongolian emperor it is claimed are secret wonders which vie with those of Tutenkhamun. Seven lamas guard the place and, so the legend runs, every seven hours one of them strikes seven times on a huge jade bell hanging above the sarcophagus. The lamas told the story of the Khan’s ghostly risings.

Told against the background of modern civilization, the story of the phantomlike tomb of Genghis Khan does indeed sound fabulous, but related against the background of all the weird legends of the Gobi Desert, the account has its proper setting. Whether or not Asia’s great archaeological riddle has been solved, the announcement with its almost fantastic details has caused once more eerie old folklore of China’s centuries-old sand kingdom to be revived.

Ghosts there could be in Genghis Khan’s sarcophagus in the Gobi, if we are to believe the tales of Marco Polo, the intrepid Venetian traveler who crossed that desolate area two centuries after the emperor died.

It would take a year and a half for a man to run from one end of the desert to the other, the famous traveler told.

“All the hills and valleys are of sand and there is not one thing to eat to be found on it. But after riding a day and a half you found water in fresh quantifies enough for 500 or 1,100.

“But here is a marvelous thing they related of this desert, which is that when travelers are on the move by night and one of them chances to lag behind or to fall asleep or the like, when he tries to gain his company again he will hear spirits talking and will suppose them to be his own comrades. And thus travelers are led astray. In this way many have perished.

“Sometimes the traveler will hear, as it were, the tramp and hum of a great cavalcade of people away from the real line of the road and taking this to be their own company they will follow the sound, and when day breaks they will find a cheat has been put upon them, and that they are in ill plight.

“Even in the daytime you hear spirits talking and sometimes you hear the sound of a variety of musical instruments and still more commonly the sound of drums. Hence travelers keep close together, all animals have bells at their necks so they cannot be easily led astray. And at sleeping time a signal is put up to show the direction of the next march. Thus is the desert crossed.”

What Marco Polo wrote was the tale he had gathered from many travelers. They all had a dread of being led astray by evil spirits, called goblins of the Gobi. And that some of these legends persist today was amply proved to Dr. Kozloff when he set out on his first archaeological expedition in the desert. When he made his attempt to locate Khara-Koto, the famous dead city of Kings, which he eventually found, the nomad tribes of the desert told him there was no such place, only an abode of evil spirits which it was impossible to approach. He, however, was not deterred and, pushing on, made his famous discovery of Khara-Koto with its quantity of statuettes in gold and silver, its tapestries and sacred Buddhist pictures and its skeletons of holy men with faces pointed toward the south. It is near Khara-Koto Professor Kozloff has made the discovery of the ancient tomb which he names as that of Genghis Khan.

So great and terrible was the onslaught of this astonishing emperor and his conquering hordes that he himself was regarded as something supernatural. The Mohammedans, fearing the end of the world was at hand, sent to their enemy, the king of France, to beg for aid against the Mongols. His own people regarded him as a sort of supergod. Easy enough it is to believe that the lamas who guard a tomb in the Gobi pass on to the privileged Mongols and Khan descendants, who are allowed to make a pilgrimage to it each year, the story of a ghostly appearance.

Genghis Khan was one of the greatest conquerors the world has ever known. In the thirteenth century heroes from a mere stripling nomad boy to be king of half of the territory of the earth. He conquered hordes with their barbaric and sometimes appealing code of chivalry, demolished whole empires and crushed countless cites to the earth. China itself, Russia, Poland, the lands of the Mohammedians all fell before Genghis Khan. His vast kingdom extended east as far as India and west into Hungary.

His orders to his soldiers were “not to hang back when an enemy was in sight, not to abandon a wounded comrade, not to fail to rescue some one who had been taken prisoner.”

“They never leave the battle,” a Christian priest of a later generation said of the warriors of the horde, “while the standard is lifted; vanquished they never ask that their lives be spared, victorious they never allow a foreman to live.”

“Follow Mohammed Shah wherever he goes in the world,” was the order Genghis Khan gave when he was in pursuit of the Turks. “Find him dead or alive. Spare the cities that open their gates to you, but take by storm those who resist.”The Mongolian was another Alexander of Macedon. Having conquered the east, his thundering horsemen plowed into the plains of Europe. The Council of Lyons was partially called by the pope to devise means of stemming the terrorizing tide.

When Genghis Khan died, so fearful were his followers that others knowing of his death would usurp his powers, before another ruler could take the throne, that he was buried with the utmost secrecy. The legend goes that the soldiers who carried him to his grave slew every one who came in the path of the funeral procession lest the secret be divulged. He was carried in turn to the ordu [Ordos?] of each of his wives, and then in solemn secrecy laid to rest in the Valley of the Killian.

Thus by chance did it happen that the grave of Genghis Khan was hidden from mankind. For centuries men have conjectured about it and sought it without avail. What happened to the body of the celebrated Mongolian conqueror has been one of the great archaeological riddles of the world. Twenty years ago Professor Kozloff, noted Asiatic scholar and explorer, set out on his determined search to find the tomb. In the course of his wanderings over the Gobi Desert he made his famous discovery of the dead city of Khara-Koto, which the Mongol emperor destroyed. And it is near the ruins of this ancient dwelling place of kings Dr. Kozloff now claims to have discovered, years later, the sarcophagus for which he set search.

The Japanese claim that Genghis Khan was their Yoshitsune, and that Tartars near Nikolaievsh wear the ancient Japanese armor with the Genji crest is laughed at as pure fiction, one authority assert. It may have arisen from a general similarity of the armor and of the pattern on Genghis’ robes to be seen in Japanese decoration.The portraits of Genghis, shown by Buddhist priests, Russians, Japanese and others, are all said to be incorrect in one way or another. The true likeness, reproduced on this page, is preserved in the old Imperial Palace at Peking. It is surrounded by his advice to the heir apparent on how to conquer the enemy. Just after he finished speaking he died.

The tomb is said to be beyond the labyrinth of passages cut into the mountainside. It is about forty feet square, built in the form of a spacious hall. Beside the silver coffin is Genghis Khan’s own story of his reign [written in Tartar and Chinese] and a life-sized lion, tiger and horse in pink jade. There is a copy of the Bible written by an English monk. [And a golden tablet presented by Marco Polo.]

The lamas related that once every year certain privilege Mongols and the Khan’s descendants visit the tomb to make sacrifice to their famous ancestor’s memory.

Professor Kozloff finally wrested the secret of the tomb from the Khan’s descendants. They led him as well to the tomb of Genghis’ favored wife, the inscription on whose white marble coffin sets forth that “the great Khan released her by placing his dagger in her breast.”

Experts of the east are proving skeptical over these discoveries, so colossal in import if the reports prove authentic. Some claim that the finding of the tomb has been confused with the only known memento of Genghis, which is a stone tablet found on the Russo-Mongolian border and which is now in an Asiatic museum. Recently the tablet, up to this period incomprehensible, was translated. It reads;

“Genghis held here a meeting of army chiefs on his return from the conquest of Khiva.”Vladimir Dostoyevski, nephew of the noted writer and an authority on archaeology, regrets the spread of reports of the finding of the tomb and the fantastic mystification surrounding it. He is a friend of Professor Kozloff and has looked for years on the valuable achievements of his fellow countryman.

In the spring of this year Kozloff started off on his expedition, having in mind particularly the excavation of a mysterious well located in the ruins of Khara-Koto and believed to contain fabulous treasure. There is a legend connected with the well which says the Khara-Kotons poured all their precious silver and jewels into its depths in the course of a battle between Genghis Khan and Hara-Tzyan, the last ruler of the fortified city. The overlord of Khara-Koto had dreamed of overthrowing the great Mongolian emperor. It was these aspirations which drew the ire of Genghis and ended in the destruction of Khara-Koto. The story of the well with its treasure has persisted through the centuries and it is believed by archaeologists some day the loot will be found.

This was Professor Kozloff’s seventh trip into the desert. More than any other man he is responsible for what the world knows about the Gobi. The Seattle [WA] Daily Times 11 December 1927: p. 2 Additions in brackets from Corvallis [OR] Gazette-Times 21 November 1927: p. 1, 6

The channeling of the year’s prophecies by the late Genghis through his priest’s hand is a nice touch, reminiscent of the “curse” said to have been found when the tomb of Tamerlane was opened in 1941 by a group of Soviet archaeologists. That tomb was inscribed: “When I rise from the dead, the world shall tremble.” and the warning “Whomsoever opens my tomb shall unleash an invader more terrible than I,” were said to be found inside the the coffin. Three days after the exhumation, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union. No curse seems to have followed Professor Kozlov, except the curse of lurid journalism.

Western papers seemed generally unable to cope with Russian and Asian names, hence some of the mangled spellings found here. Professor Kozloff was Pyotr Kuzmich Kozlov, a Russian archaeologist who spent many decades exploring the Gobi and the “lost city” of Khara-Khoto. He was awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s Founder’s Gold Medal in 1911 for his work in Central Asian exploration. Not, perhaps, a man to make up fanciful accounts of lions and tigers and crowns, oh my! But his work seemed to make the press corps go full Sax Rohmer. An earlier article on Kozlov’s work made an even more fantastic claim:

WAS MONGOLIA BIBLE’S EDEN?

Fossil Remains Indicate It May Have Been Birthplace of Man and Beast.

(By Associated Press.)

Urga, Mongolia, Sept. 23.-Professor Peter Kozloff, Russian explorer, has discovered near an enormous number of skeletons of hitherto unknown animals and many human remains which lead him to believe that Mongolia may have been the birthplace of man and the point of origin of a considerable part of the animal and reptile world.

Among the fossils already unearthed by Prof. Kozloff and his associates are those of 25 quadrupeds of undesignated species, 150 birds of varying, sizes. 100 reptiles, snakes and fishers and more than 1,000 insects of giant size.

It will be recalled that Prof. Kozloff last June discovered several remarkable tombs near here belonging to the Chinese emperors and princes who ruled Mongolia at a time antedating the pharaoh Tutankhamen of Egypt.

More remarkable perhaps than Kozloff’ s discovery of animal and human fossils is. the fact that he has also found in one of the royal tombs bricks of compressed tea and grains of wheat still fit for human consumption despite the fact that they have lain in the tombs many thousands of years.

Bronzes Found in Grave.

In another section of this district Prof. Kozloff excavated the grave of a woman of the nobility, containing a number of bronze articles of exquisite craftsmanship and several silk tapestries of superb texture which depict Greek and Roman figures on horseback.

The nature of his discoveries is so important that the Russian scientist has decided to remain in Mongolia indefinitely postponing until next year his expedition Into Thibet to resume exploration work in the forgotten city of Kharakhoto, which he unearthed some years ago. Three archaeologists and biologists are now enroute here from Leningrad to assist Prof. Kozloff,

Prof. Andrews’ second expedition to Mongolia comprising 13 American scientists and a staff of 40 other Americans is expected to arrive here next spring from Peking. It is newspaper-understood they will confine themselves to research and exploration in human evolution, endeavoring to establish that the central Asian plateau is the cradle of the human race.

The Republic [Columbus IN] 23 September 1924: p. 4

The question is: is there even a shred of truth to the fantastic story of the coffin and the seventy-eight crowns, the lamas, or the jade bell? I don’t read Russian, so what, if anything, did Professor Kozlov find? Was it really likely that descendants of Genghis Khan would suddenly tell him where the tomb was, even if they knew?

Or is it more likely that Kozlov is describing what is known as the mausoleum of Genghis Khan? This building, which has gone through multiple incarnations, destroyed and rebuilt as governments rose and fell, was first erected at the base of the Khentii Mountains after the Khan’s death, as a shrine displaying some of his possessions. Around 1368, the shrine was moved to the Ordos district of Mongolia, into a series of yurts where the Khan had lived. A large, permanent structure was erected in the mid-1860s. You can read something about the checkered career of the building and its contents here. It was moved, replicated, and rededicated multiple times. I assume that some kind of shrine, whether in a yurt, temple, or cave, existed in the 1910s and 1920s. Just to be pedantic, the shrine, which is now a very popular tourist attraction, more properly ought to be termed a cenotaph—a mausoleum houses a body or bodies.

The Silver Coffin of Genghis Khan. The Mausoleum of Genghis Khan, By Fanghong – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4960386

Curiously, there is a story from 1939 that describes the “bones of the Khan” as resting in a coffin of silver. The story, by George A[shmore] Fitch, a missionary, Y.M.C.A. worker and Director of the Nanking Safety Zone International Committee, tells of moving the actual bones of the Khan from Paotow to Lanchow [sic] to keep them out of the hands of the Japanese invaders. Fitch, who says he witnessed the moving of the remains and photographed the convoy wrote:

“A commission was sent to Prince Kung-pu Tsa-pu, the direct lineal descendant of Genghis Khan, and in a council of Mongolian leaders it was agreed that the remains of the great empire builder should be removed to a safer place.

The casket of solid silver, together with two other caskets containing his helmet, sword and official robes, were removed from the mausoleum at Chuin Wang Chi, placed in a new truck, well padded with silk quilts, and, accompanied by a guard of Chinese soldiers as well as of Mongol bannermen, was taken by stages to a beautiful temple about 20 miles southwest of Lanchow, provincial capital of the northwestern province of Kansu.” The San Bernardino [CA] County Sun 12 November 1939: p. 28

Were these really the bones of Genghis Khan or merely relics from the shrine kept in a solid silver coffin? We might indulge in a flight of fancy and ask the question: is the term “mausoleum” [and the current attraction seems to be billed as the “burial mound” of Genghis Khan] not actually a misnomer; are the bones of the Khan hiding in plain sight in a silver coffin?

The 1927 story of the tomb’s discovery may be just another case of a correspondent exaggerating or mistakenly reporting archaeological news from abroad. (Not unlike the hoax report from earlier this year that the tomb of Attila the Hun had been located.) If the press invented or enhanced a ripping yarn starring Professor Kozlov, is there perhaps a fictional inspiration for the black slab of prophecy, the jewel-studded weapons, and the huge jade bell? They seem like stock properties from a Theosophical novel.

Write with the priest’s hand to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.