Touching the Corpse: Late Examples of Cruentation

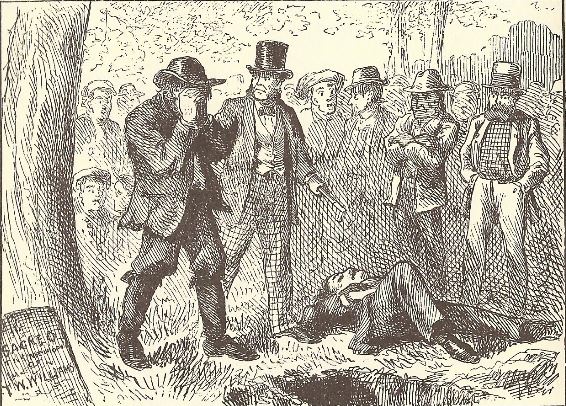

Touching the Corpse: Late Examples of Cruentation In Tom Sawyer Joe stands by the corpse of one of his victims as Muff Potter is accused.

Injun Joe helped to raise the body of the murdered man and put it in a wagon for removal; and it was whispered through the shuddering crowd that the wound bled a little! The boys thought that this happy circumstance would turn suspicion in the right direction; but they were disappointed, for more than one villager remarked: “It was within three feet of Muff Potter when it done it.”

-The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Mark Twain, 1876-

The notion that a corpse would bleed in the presence of a murderer is known as cruentation. It has a long history—some say the practice is mentioned by Homer.

The blood especially was the very self. It is this belief that explains the idea that the corpse of a murdered man bleeds in the presence of, especially at the touch of the slayer. There are references throughout the literature of the Middle Ages to the bleeding-corpse or cruentatio. It occurs in the Nibelungenlied. And in the Ivain of Chretien de Troies, there occurs a scene where the corpse is brought into the hall where Ivain is, and then begins to bleed, whereupon the men feel confident that the murderer must be hidden there, and they renew their search. The soul is regarded as speaking through or by the blood. In the Highlands 1 I feel confident that there are remnants of such a belief, pointing back to a belief similar to the thought of the Hebrews when they held that “the blood is the life” (Deuteronomy xii. 23). To be remembered, too, are Homer’s expressions: “The blood ran down the wound” (Iliad, xvii. 86); “the life (ψυχή) ran down the wound” (Iliad, xiv. 518). A Greek, quoted by Aristotle (De Anima, i. 2, 19), declared that the soul was the blood. The Arabs say “the soul flows” (from the wound), i.e. he dies.

Survivals in Belief Among the Celts, by George Henderson, [1911], p. 38 at sacred-texts.com

See, also, this admirable article by the Chirugeon’s Apprentice for some early examples.

And here, at the always fascinating Executed Today blog, for links to more examples.

The curious practice continued well into the 19th century. Here is one, vividly described, from 1818 Ohio.

One of the most thrilling circumstances of which I have recollection—and it was an occurrence that aroused the most profound and wide-spread interest among the pioneers of the Scioto Valley,” said Mr. Emmitt, “was a murder trial that occurred at Sharonville, in 1818. It was, I have no doubt, the most weird performance of the kind that has ever taken place in Ohio, and it made a life-long impression upon all those who were present at the arraignment of the man accused of the crime — an arraignment as horrible as the mind of man can conceive.

“One morning, in 1818, a man named Williams was coming through the woods, adjacent to his home. This man Williams had a brother, of whom he was intensely jealous, and they had quarreled a few days before. Williams was carrying his gun—a custom then universal among the backwoodsmen—and when about three miles from Waverly, he saw a man sitting on the ground, with his head resting against a tree. Williams took the man to be his cordially hated brother, and acting upon a murderous impulse, he raised his gun and discharged its contents into the head of the sleeper, killing him almost instantly. To Williams’ utter consternation, he discovered that the man he had murdered was not his brother, but an inoffensive neighbor named Louis Sartain. Williams left his poor victim in the woods and went on his way to transact the business he had started out to look after. Sartain was missed from home, a search was instituted for him, and after a few days, his ghastly remains were found lying in the woods, with a bullet in his head.

“Sartain was buried, and then a few pioneer detectives, spurred on by the united sentiment of the settlers, began a vigorous endeavor to discover his murderer. Williams was suspected of being the guilty man. He was rather a hard character, of vindictive disposition,-and quick to quarrel. Tracks were found about the spot where the murder occurred, which were similar in size to the shoes worn by Williams. The bullet recovered from Sartain’s head was found to be identical with those constantly used by Williams— made in the same mould, to all appearances.

“These were the strongest evidences of guilt that could be adduced against Williams, and there were many circumstances that tended to make the detectives doubt their trustworthiness. They knew that Williams had never had any trouble with Sartain, who was, in reality, a man with no known enemies. He was a good-natured, easy-going fellow, whom almost everybody liked. The detectives, who had watched Williams’ actions very closely, could discover in him nothing that would tend to confirm their suspicions. He went about in a quiet, unconcerned, every-day sort of way; discussed the murder with his neighbors; wondered with a decent show of interest who could have committed the crime, and expressed himself in easily understood terms regarding the character of the punishment that should be visited upon the assassin, when he should be discovered. All this time, Williams was fully aware that public suspicion accused him of the murder. No one sought his arrest, because the evidence was lacking to prove his guilt.

“A month passed, and the belief became more firmly fixed than ever, in the public mind, that Williams was the murderer of Louis Sartain. For centuries past, there has existed in Ireland, and in portions of England and Scotland, as well, the superstitious belief that if a murderer places his hands upon the body of his victim, the wounds of the person murdered will gape and bleed afresh. In the south of Ireland, the most implicit confidence is placed in this infallible murder test, as it pleases them to so believe it. This same belief found many adherents among the pioneers of the Scioto valley, who were quite liberally tinctured with Celtic blood. And after all other means of discovering the slayer of Louis Sartain had been exhausted, it was proposed, by some of the older people, to have Sartain’s body resurrected, in order that a final supreme test might be made— a test which, it was fully believed, would fasten the responsibility of the black crime upon Williams.

“A public meeting was called, the project discussed, and the determination reached to take Sartains body from the grave, place it in a public place, summon every man in this section to attend the “trial by blood,” and compel every person in attendance to place his hands upon the body.

“A committee was appointed to resurrect Sartain’s remains under legal authority and remove them to the old stone Baptist church, near Sharonville, where they were exposed to public view, on a certain day, when all the country round was summoned to be in attendance. Poor Sartain! His corpse presented a horrifying sight to the great concourse of people that gathered at the church, in response to the constable’s summons, or the promptings of curiosity, that was wrought to a wonderful pitch. The murdered man’s hair and beard had grown fully one-half an inch, and his body was fairly alive with slimy grave worms, that were feasting upon his flesh. The stench arising from the decaying body could not have been endured under less exciting circumstances. Every man, of course, felt it his duty to vindicate himself, inasmuch as all had been publicly and officially called upon to subject themselves to the test of touching the dead body; and all believed that they could do this safely, save Williams. They confidently expected to see the gangrenous wounds of Louis Sartain gush out a stream of accusing blood the moment Williams entered the room — or surely when he dared place his hands upon the foul-smelling body.

“John Shepherd, who was then constable, was Lord High Master of Ceremonies. He was a very officious fellow, with a smattering of education, and was known far and wide because of a wonderfully confusing infirmity of speech. He talked through his nose, and after the most outlandish manner possible. He stationed himself near the platform on which Sartain’s body lay, and called upon each man in turn, by name, to step forward and go through the fantastic programme arranged for the occasion. Samuel Corwine, against whom there was, of course, not the faintest breath of suspicion, was the first man called, and this is the way Shepherd officially notified him:

“Sabued Cudwide! Sabued Cudwide! Cobe upad touch de dead body ob Louis Sartain, subbosed to be shot or murdered!”

Mr. Corwine quietly walked up to the body, examined it, placed his hands upon it and retired. The body didn’t bleed.

“Uccle Tede Howa’d! Uccle Tede Howa’d!” shouted Constable Shepherd, who wanted Mr. Cornelins Howard to step forward.

“Cobe forrud, Uccle Tede, an’ touch yo’ han’s to de murdered man’s torps.”

“Uccle Tede” was not a second Moses. He, too, failed to draw blood from Sartain’s body.

“And one by one, in answer to their names, the men there gathered, filed in, touched the corpse and stepped aside—all but one man, Williams, who stood calmly just without the house and awaited his summons. His, by preconcertion, was the very last name called. Those who had successfully passed the dreadful ordeal crowded the room, reeking with the most frightful stench, waiting for the appearance of the one man, to entrap whom was the inspiring idea of that almost barbarous performance.

Williams walked into the room with a steady step. He was pale, but not nervous. He knew the prompting motive of that extraordinary trial. He knew that it was designed for his sole benefit. He knew that his neighbors believed him guilty of the murder. He knew that the majority of them firmly believed that the worm-eaten body of Louis Sartain would accuse him of the unwitnessed killing in the woods. He knew that the moment was one of supreme consequence to him. He knew that his every movement and expression were watched by three hundred pairs of eyes, and that he must exert fairly superhuman control over himself. He knew that he was guilty, as silently charged, and he probably had a sickening fear that tell-tale streams of blood would really issue from the bullet-hole in Sartain’s head. But in the face of it all, he walked up to the offensive smelling corpse, examined it all over with an apparent show of interest, touched it as the others had done, and passed on out of the room. The corpse didn’t bleed anew, and the “infallible” murder test was secretly voted a flat failure by scores of persons, who were not convinced of Williams’ innocence, simply because “Louis Sartain’s corpse failed to do its duty. It was too long in the grave,” so some of the well-seasoned, superstitious heads decided.

Williams was never punished for the crime; but retribution, swift and terrible, came to him a short time after the trial. There was a great mill and distillery combined in operation at Richmond-Dale at that time, and it was there that Williams and Joe Mounts met one day, while both were drinking. Mounts was a hard character. The two men got into a quarrel, and Mounts struck Williams on the head with a wooden roller, used about the mill in handling buhrs. A portion of Williams’ skull was crushed in, but he was not killed outright. A quack doctor named Allison was sent for, to dress the wound. Allison couldn’t get at the broken skull, to raise it up and restore it to its old position, so he took a common half-inch auger and bored a hole into the sunken piece of skull, in order that he could get a hold upon it and lift it back into place. Of course, Williams died. His injury was a fatal one, but even if it hadn’t been Allison would have finished him.

Life and Reminiscences of Hon. James Emmitt: As Revised by Himself, James Emmitt, 1888

James Emmitt [1806-1893] of Pike County, Ohio was a genuine Character. Much of what we read in his Reminiscences, a ghost-written autobiography “as revised by himself,” has a favor of tall tale about it. But an author of a Pike County history who knew Emmitt wrote: “For his recollections, he may be considered a walking history of Pike county, and from this source much herein is derived,” so we have no reason to believe that this account, lurid as it is, is false. He may have actually attended the trial as a 12-year-old boy or heard about it from eye-witnesses.

It is obvious that the psychology of the individual would account for some of the effectiveness of this method of forensic detection. A murderer less cool than Williams would naturally be afraid to touch the corpse of his victim and such would be noted by onlookers. It was also hoped that the murderer would be terrified or startled into a confession when confronted with the body.

The next case arose from a sensationally brutal case from 1833 Pennsylvania. Charles Getter murdered his wife Rebecca, to whom he had been married only ten days. He was engaged to another woman, but was brought before the Justice of the Peace by Rebecca who accused him of fathering her unborn child. To avoid being jailed, he married her “after an hour’s deliberation, in which he evinced much repugnance to the union.” He refused to live with Rebecca and was heard saying that he would be rid of her inside of three weeks. Her strangled body was found near her home shortly thereafter. A witness told of this variation on the bleeding corpse during the trial:

From the Philadelphia Intelligencer.

TOUCHING THE CORPSE

We did not suppose that the superstition of touching the body of a murdered person, to ascertain the murderer, had its believers in this country. We find, however, in the trial of Getter, who will be executed next Friday, at Easton, for the murder of his wife, the following passage of evidence.

“Julianna Leitz, sworn. If my throat was to be cut, I could tell before God Almighty, that the deceased smiled when he (Getter the murderer) touched her. I swore this before the Justices, and that she bled considerably. I was sent for to dress her and lay her out. He touched her twice. He made no hesitation in doing it. I also swore before the Justices, that it was observed by other people in the house. This was towards evening, when the doctor and jury (coroner’s) were gone.”

Columbian Register [New Haven, CT] 12 October 1833: p. 3

Even later was this example from South Carolina.

A Corpse Bleeds at the Murderer’s Touch.

The Columbia, S.C. Union contains the following account of a murder which was committed in Orange County on Friday, the 9th inst. Jeffrey Heisey and Russell Wilson had some difficulty that morning about a place which Heisey bought for $6,000. He had just returned home and was sitting down at his house with a woman and two children, when he was shot through a crack in the window. The wound was a horrible one, shooting the whole under jaw away and throwing the tongue on the floor. The women and children were wounded. Mr. Heisey died almost instantly.

The verdict of the Coroner’s jury was that he was shot by Russell Wilson, who is now in jail. The old idea that if the murderer would place his hand on the corpse of the murdered man the blood would flow, was tested on this occasion, and we are reliably informed that the Coroner required all the jury to lay their hands on the body. When Russell Wilson touched the corpse, twenty-four hours after his death, the blood flowed full and free from the corpse. On the following day, while Rev. Mr. Guignard was delivering the funeral service over the grave of the murdered man, the premises of the minister were set on fire and utterly destroyed.

Jackson [MI] Citizen Patriot 31 January 1874: p. 2

Another other late examples of judicial touching of the corpse? Send to the squeamish chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.