Consumption Cottage

Consumption Cottage A cottage infected with consumption.

Recently I’ve been fascinated by “hoodoo” or “unlucky” or “ill-starred” houses where the body counts pile up. Today, for World TB Day, we visit a house haunted by the ghosts of consumption.

THE STORY OF A COUNTRY HOUSE.

By GEORGE THOMAS PALMER, M. D.,

President of the Illinois State Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis.

One becomes accustomed to lurid tales of disease and suffering in the city slums. The resident of the country town is prepared to believe any sort of story dealing with the unnecessary sacrifice of human life in great centers of population. He hears such stories with a certain smugness and self-satisfaction. He forgets,—if he has ever known,—that there are usually disease breeding slums in every city, town or hamlet, regardless of its size or location.

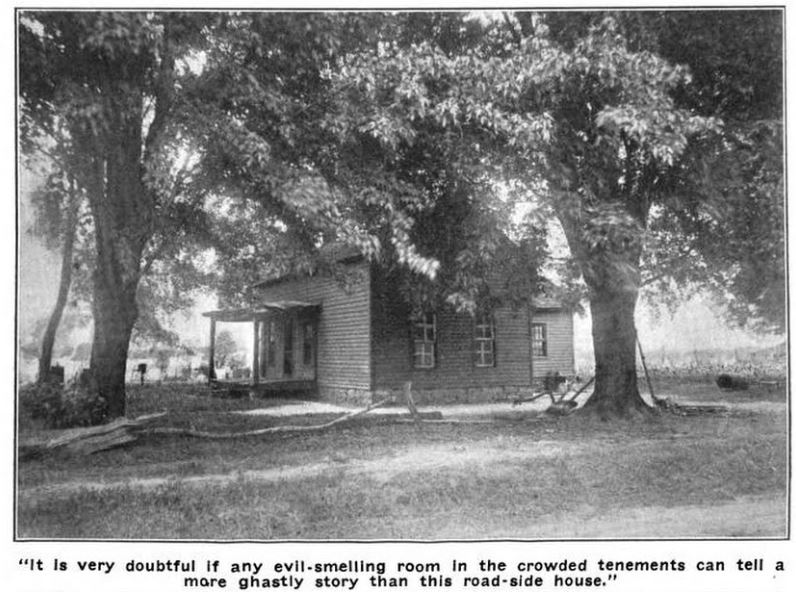

Over in Effingham County, in the outskirts of a prosperous town, stands an old house, situated pleasantly enough in the shade of two giant maples. The country road sweeps past it and green pastures and fields of corn extend away as far as the eye can see. In the morning, robins and jays and thrushes run riot in the trees. There is something homelike in the very dilapidation of the place.

Certainly this is not slums!

But it is. It is very doubtful if any dark and evil-smelling room in the crowded tenements of Chicago can tell a more ghastly story of the sacrifice of human life than this road-side house in Effingham County.

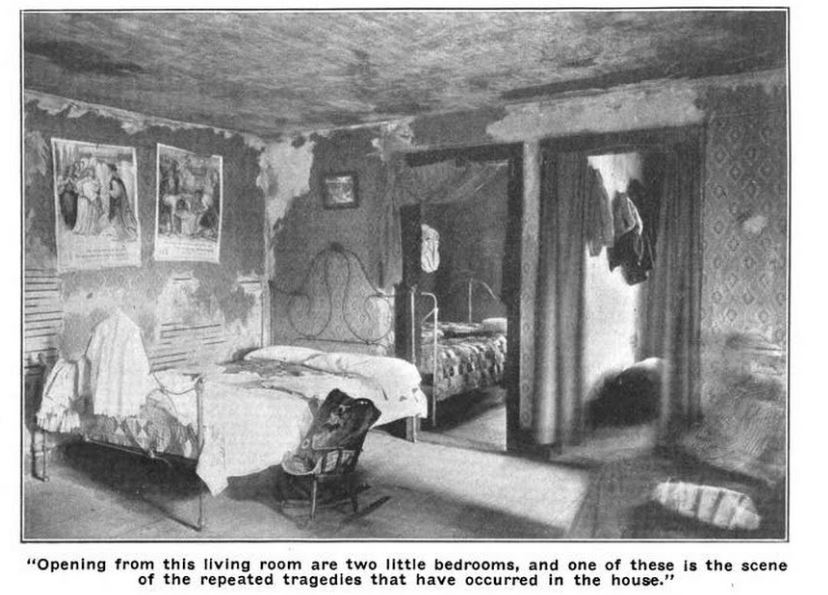

There is nothing very unusual in its appearance. It is old and unpainted; the weather boards are loose and broken and in many places the fallen shingles have left exposed gaps in the roof. Within, there is a living room of moderate size, the wall paper stripped off and with large spaces where the plaster has fallen and the lath are seen. The smooth coat of the walls is almost gone and the rough sand surface is broken in hundreds of places where nails have been driven. The floor is worn and rough and broken.

Opening from this living room, and similarly dilapidated and out of repair, are two little bedrooms, about seven by ten feet in size and one of these is the scene of the repeated tragedies that have occurred in the house during the past fifteen years.

Consumption Cottage The “death room” in the cottage, where an unusually large number of its inhabitants died of consumption

In this room, incidentally, in the year 1900, a man died of tuberculosis. With the death of this man, his wife and children moved away and another family moved in. In this family was a young woman. And this young woman sickened and, in a few months, she died. She died from tuberculosis. She had slept constantly in the room in which the former householder had died.

And so the second family moved away and a man and his wife moved in and occupied the ill-fated bedroom. Ten years ago—in 1904—the wife of this couple died in the house. She died from tuberculosis.

The young widower vacated the place. Shortly after, there moved in a man and his wife and a family of children. So far as can be learned, they were all in good health at that time. But that was several years ago.

It was not long however, until a son of the household,—a young married man,—sickened and, after a while he died,—from tuberculosis, and his young widow went back to her old home town where she died from tuberculosis, leaving two children who were placed in a charitable institution.

Then came the death of a little child in the “death room”;—a death from miliary tuberculosis,—and the following year, the mother of the family died from tuberculosis and was buried at the expense of the county,— for by this time the disease and the expense and inefficiency which go with it were beginning to render the family destitute.

The year following that in which the mother and infant died, a married daughter succumbed, leaving behind her two children, both of whom are now dead, one certainly having died from miliary tuberculosis.

The next year another grown son of the family became a victim of the disease. In 1913, a married daughter, who had been raised in the house and who had left it as a bride, came back to the ill-starred home and died of tuberculosis, leaving three small children who have been farmed out among relatives of the husband.

Just a few weeks ago, another daughter, twenty-one years of age was claimed as a victim of tuberculosis, dying in the little “death room.”

This seems a shocking record for the ramshackle old house;—but it is not all. One of the daughters, who had escaped death in the place, married a prosperous young farmer and moved away. She became the mother of six children, one of whom died from tuberculosis following whooping cough. And then this young mother died of tuberculosis and her remaining five children were farmed out with friends and relatives.

And then another daughter was married and moved to an adjoining county. When she was but developing into womanhood,—at twenty years of age,—shortly after the birth of her first child—she died of tuberculosis and her baby followed her in death—a victim of tuberculous meningitis.

And now of that ill-fated family but three remain,—the father and two children, a boy of ten and a girl of fourteen. The father is gaunt and emaciated. The two children show evidences of the disease which will probably eventually claim them.

While the death record of the house, as it is now written, seems appalling,–while the story of motherless children and of their dependence is impressive—one can only guess at the extent to which the baneful influence of the place will spread. Already the blight has extended into other communities. Already, perhaps, the infection which will wreck other homes has been implanted.

And yet, tuberculosis is a preventable disease.

It takes no very fanciful imagination to see the dreadfulness of all this; but even to the sordid and the cold-blooded there is a definite and unpoetic appeal. This house is said to have already cost the county of Effingham over $2,000.00 for material aid, for medicine, for doctors and for funerals. And that $2,000.00 has not begun to solve the problem.

The house has enormously increased the “pauper expense.” Tuberculosis is not a disease of paupers; but it is essentially a pauperizing disease.

Illinois Health News, Volume 1, 1915: pp. 69-71

Sixteen–perhaps nineteen, by the time this article was published–victims of a “preventable disease….” Precisely just how preventable tuberculosis was at this time is open to debate. Many physicians felt that proper diet, rest, fresh air and sunshine would keep the dread scourge from taking root. Others believed that consumption was caused by intemperance and vice (with a side-order of damp sheets and airless rooms) and that only the weak and lazy would succumb, leaving the fittest to survive and strengthen the gene pool. I find it interesting that the author, Dr. Palmer, seems more interested in the public expense, rather than the human toll, as he makes that crack about “inefficiency” in the same breath as noting that the mother was buried at the expense of the county and speaks of the “dependency” of those orphaned children.

The author worked with the Illinois State Board of Health and also edited The Chicago Clinic and Pure Water Journal, which, despite its subtitle of “A Medical and Surgical Journal,” gave “special attention to climatology and mineral water therapy.” In other words, he was something of a water-cure advocate, which, at this late date makes him a medical maverick. Am I imagining things, or is he hinting that the house itself is the source of infection and that the “death room” is a lethal chamber for all who occupy it? I’ve certainly heard of sickroom flowers held responsible for carrying “morbific bacteria” and poisonous wallpapers shedding arsenical green to be inhaled or ingested, but neither are cited here. He mentions “slums,” a notorious breeding ground for urban consumption, but there is no suggestion that, despite its disrepair, this house replicates the tenement’s cramped and noxious environment, nor does he remark on how frequently the disease annihilated families.

Despite the bare laths and what looks like mold on the remaining plaster, the metal beds (to prevent bed-bugs) are neatly made with patch-work quilts and someone has made an effort to decorate with a picture over the bed and (Biblical?) prints tacked to the wall. It is a pathetic attempt at respectability in the face of the shadow of death.

As a completely irrelevant aside, is the sentence quoted as the caption on the first image meant to echo Sherlock Holmes’ “It is my belief, Watson, founded upon my experience, that the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.”?

Other examples of lethal houses? Check to see if you have a hectic flush before sending to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of A is for Arsenic: An ABC of Victorian Death, The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.