Monsieur de Paris’s Orchid Buttonhole

Monsieur de Paris’s Orchid Buttonhole A working guillotine model carved in bone.

It is Bastille Day and naturally one’s thoughts turn to the guillotine.

France is noted for its bureaucracy and its nineteenth-century arrangements for executions followed a tidy, centralized pattern. At the fall of France’s Second Empire, separate executioners for each criminal court were eliminated in favor of a chief executioner for the whole of France. “Monsieur de Paris,” as he was known because he was to live in the City of Light, would be required to “proceed to any city or town in France to execute criminals condemned to death.” In the late 19th-century, he had a regular salary of 6000 francs, plus 1800 francs for “care of the guillotine.” In addition, he was allowed first-class railway expenses and a daily stipend when travelling. He had five assistants.

The post was hardly a sinecure. The work was stressful and occasionally dangerous. As they had been since the Middle Ages, executioners were societal outcasts; the various executioner families intermarried; their sons succeeded them in the family business, and despite using false names, executioners’ families were often driven from respectable suburban neighborhoods.

Today we meet one of France’s last public executioners, Louis Antoine Stanislas Deibler. What follows is a loosely conceived obituary written for the American press, with quite a few sensational touches.

RING

Of Iron Was Made

From the Blood of Those Executed By Deibler

Noted Headsman’s Death Recalls Odd Acts

And the Eccentricities of a Gruesome Career,

In Which 502 Murderers Died By the Knife.

Eyewitness Tells of the Neatness and Dispatch With Which a Texas Cowboy Was Guillotined.

By Paul Villiers

Special Cable to the Enquirer.

Paris, September 10. The most interesting event of the week in France was the death and burial of Louis Deibler, the famous executioner of Paris, who himself had been the agent of death 502 times. He died at Auteuil Thursday, and was buried Friday. His son, Antoine [Anatole] Deibler, the present executioner, was chief mourner, and two assistant executioners attended.

Deibler, better known as “Monsieur De Paris,” was 81 years of age. He succeeded the almost equally famous Rasseneuf, whose chief assistant he had been, in 1871. It was his greatest boast that in all his long career he had never met with a mishap. He amassed a considerable fortune during his term of office. He came from a family of executioners, his father having been at one time chief executioner [of Rennes]. His son Antoine [Anatole] is the present executioner, and his wife was a daughter of a former executioner of Brittany, while his daughter is engaged to marry another executioner in one of the French colonies.

Proud of His Work.

Deibler’s reason for retiring was that his hands were becoming unsteady and that his long service entitled him to a rest. He took a great deal of pride in his work and often expressed the hope and belief that a decoration would be awarded him by the Government for his faithful service.

Deibler was given to many eccentricities. One of his unique acts was the manufacturing of a ring made of iron extracted from the blood of each of those at whose official death he officiated. At the time of his death Deibler was engaged in an elaborate work entitled “The Death Penalty in Europe.”

Among the 502 murders, executed by “Monsieur De Paris” was young Sellier, the Texas cowboy, who killed two gendarmes.

Passing of a Landmark.

Pierre de Goncourt, a witness of the execution of John Sellier, gives the following description:

“The news that Louis M. Deibler is dead affects me. It is the passing of a landmark, although five years ago he turned the office over to his son, and has since lived as plain M. Moreau.

“He was an estimable character, and I shall always hold in memory the sight of the eminently respectable and Bourgeois old gentleman who had put to death 502 persons, and whom I saw press the button that dropped the keen-edged blade upon the neck of young Sellier.

“Deibler was very skillful, and his executions were free from annoying and unpleasant features. It was said by the common folk that he was possessed of the “evil eye” and that he controlled those he was about to kill by hypnotizing them.

“On the occasion of the putting to death of the cowboy there was no need of hypnotism. In the marketplace in front of La Roquette, where the guillotine had been set up, a large crowd had gathered. Suddenly, through a lane made by the police a handsome carriage was driven up. It was one of the finest carriages in Paris, with liveried driver and footman and a monogram on the panel.

Orchid in His Buttonhole.

“From the carriage stepped M. Deibler, a Parisian fashion plate. He was dressed in exquisite taste. He was an elderly man, then 75 years old, but he walked erect and as firmly as a man half his age. He wore a high hat, a black frock coat, gray trousers, and patent leather shoes. In his buttonhole was an orchid.

“He stepped upon the platform and examined “the widow” (familiar name for the guillotine) carefully, looking over every part as a jeweler examines a gem. The crowd cheered wildly.

“Then the prisoner, calm and undisturbed, smoking a cigarette, walked to the place of execution. M. Deibler had taken his stand by the left post, his finger resting lightly upon the button that releases the blade.

“Then the button was pressed and the blade dropped and Sellier’s head dropped into the basket.

“With me at the time of the execution of Sellier were Charles H. Elmore, a dealer in wheat in Chicago, who was greatly impressed with the neatness and dispatch of the performance, and a man named Fowler whose first name I have forgotten. He was engaged in floating a mining scheme in Paris and was from San Francisco. He had been in all sort of shooting scrapes in the West, but when the head of Sellier flipped off into the air and then flopped into the basket he turned white about the lips and began to inquire about the possibility of getting a cocktail.”

The Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 11 September 1904: p. A1

This article is marred by more than a few inaccuracies. I’m not sure who Pierre de Goncourt is supposed to be–perhaps Marc-Pierre, the father of Edmond and Jules? I can find nothing about “John Sellier,” the “Texas cowboy” [called “the Ghoul,” in another article] Deibler’s son and successor’s name was Anatole, not Antoine. Deibler went to great pains to pass through the streets of Paris anonymously; a carriage with a monogrammed door (unless the monogram was “M de P”) would have been out of character. His “firm walk” is belied by other accounts of a limp supported by an umbrella–one leg was shorter than the other. He was as silent as the grave about his own views on capital punishment and almost certainly was not writing a work on the subject. The notion of a ring made from the blood of his victims, while a wonderfully lurid and Fortean notion, seems to be chemically improbable.

Finally, the number of his “clients,” as he called them was nowhere close to 502. Author Sterling Heilig spoke to his son Anatole about the total:

“At the moment of his death it was cabled to America that the total number of his victims amounted to 357, an evident exaggeration, which would average seventeen a year! I said this to his son. To my surprise he sadly shook his head and said: “You forget the many years my father served in Algiers!” Kansas City [MO] Star 21 April 1907: p. 2

A casual, yet horrifying reminder of the cruelties of the French occupation… His actual total was probably between 140-160.

The life, character, and working methods of Louis Deibler seemed to fascinate 19th-century journalists. There was quite a bit of controversy over capital punishment and the contrast between the immaculately-dressed executioner and the guillotine, a barbarous remnant of the French Revolution, seemed to jar the gentlemen of the press a good deal. Deibler was described as “a modest, retiring little man, with soft, dreamy blue eyes.” He played the violin, modeled porcelain vases, was an enthusiastic angler, enjoyed cards over a cup of coffee, and was never separated from his umbrella. Such a banal, bourgeois character could not possibly interest the tabloids. Despite a claim that Deibler was never photographed or interviewed and always refused to comment on capital punishment, sensational stories were told about him:

Only once in his long and active professional career did Louis Deibler “bungle” the decapitation of a “client”—to use his own delicate, but grewsome, phraseology. This was of Laprade, the young athlete, who was guillotined at Agen in 1879. Laprade offered such violent resistance that, in spite of his handcuffs and chains, he knocked down two of Deibler’s assistant, and a terrible struggle beneath the guillotine ensued. Deibler, who was exceedingly nimble and muscular, finally managed to trip up his assailant with his left foot, and, after beating him on the temple with a paving stone until the unfortunate wretch became senseless, seized him by the nape of the neck, pushed his head through the hole and let slip the knife. Singularly enough, this was Deibler’s first operation as chief executioner. All his subsequent executions were carried out with remarkable skill and celerity.

The writer witnessed Deibler’s execution of Pranzini in the Place de la Roquette. It was at daybreak on an August morning. Pranzini [St. Therese of Lisieux’s “mon premier enfant“], who, according to custom, was unaware of the date of his execution, had been awakened from a sound sleep. Fortified with three copious glasses of rum and provided with a cigarette, which he smoked until the last moment, Pranzini, pale, but determined, was led forth by two assistants, one of whom was Deibler’s son. Suddenly Deibler tripped the condemned man with his foot, and in an instant Pranzini’s head emerged from the fatal hole, and down came the knife with a dull thud. The head dropped into a deep, square box half filled with sawdust. The trunk of the body was placed in a deal board coffin, which, together with the box containing the head, was put in a four-wheeled cart attached to a pair of horses and driven at a rapid pace to the medical school, and deposited there to be dissected or experimented upon by the students.

In the later part of his career Deibler became exceedingly nervous. He suffered from mental depression for three days after every execution. It was at the decapitation of Starch at Nancy that he was for the first time affected by “emoto-phobia,” a malady that frequently attacks executioners. After the guillotine operation had been skillfully and neatly performed, Deibler became deathly pale, and exclaimed: “For God’s sake bring water and soap! I am all bespattered with the man’s blood! Water, water—quick!” The attendants looked at him in amazement for there was not a single stain of blood upon him. Nevertheless, Deibler continued to “see red,” as the French say. He imagined that he was dripping with blood, and his agony was as intense and acute as that of a man suffering from delirium. Deibler became seriously alarmed at this access of “emotophobia,” which singularly enough, was the disease that had caused the death of his predecessor, Roch, who was himself the son and nephew of public executioners. It was soon after this episode at Nancy that Deibler petitioned the minister of justice to place him on the retired list. Springfield [MA] Republican 9 October 1904: p. 7

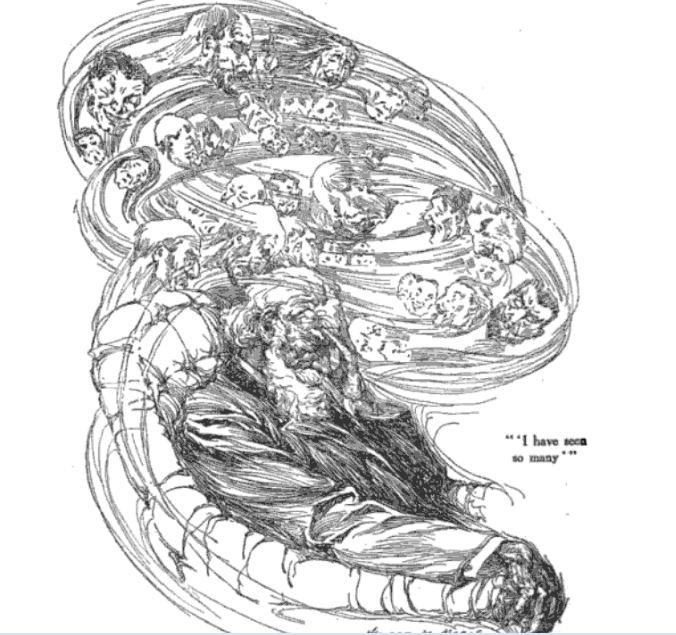

Monsieur de Paris’s Orchid Buttonhole Monsieur de Paris: “I have seen so many.”

Deibler was said to possess “a vast collection of grewsome curios and relics, the gem of the whole lot being the guillotine blade which served to decapitate King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette.” New York Tribune 31 January 1892: p. 21

Public imagination imbued Monsieur de Paris with the physiognomy of a fiend:

One day he was ordered to proceed to Ava to guillotine a curate named Bruneau, who had murdered his vicar. The execution was postponed, and Deibler passed the time fishing into the Mayenne. Upon this occasion he took his meals at the table d’hote of the hotel instead of in his rooms, as was his usual custom. He was, of course, incognito at the inn, where he had given a false name. At the table d’hote the conversation turned upon the execution that was about to take place. One of the guests said: “It seems that Deibler has arrived in town. I would give anything to see what he looks like.”

“Ah,” rejoined another lodger, “it would be easy to recognize him. He has a lugubrious, razor-shaped head, with glistening, bloodshot eyes.” Then, turning to his left-hand neighbor, who was no other than Deibler himself, he asked, “Isn’t that your opinion, too, monsieur?” Deibler replied: “No doubt. He must be a man that one would not care to meet face to face.” When the dinner was over Deibler arose, bowed politely to those present, and slowly retired. He had, however, placed his visiting card near his place, and his neighbor, leaning over to examine it, read:

‘Louis Deibler

Executeur des Hautes Oeuvres.’

Kansas City [MO] Star 21 April 1907: p. 2

Monsieur de Paris’s Orchid Buttonhole Monsieur de Paris and his wife

Deibler’s wife, who had been the daughter of M. Rasseneuf, the public executioner of Algiers, sometimes accompanied him to executions in disguise.

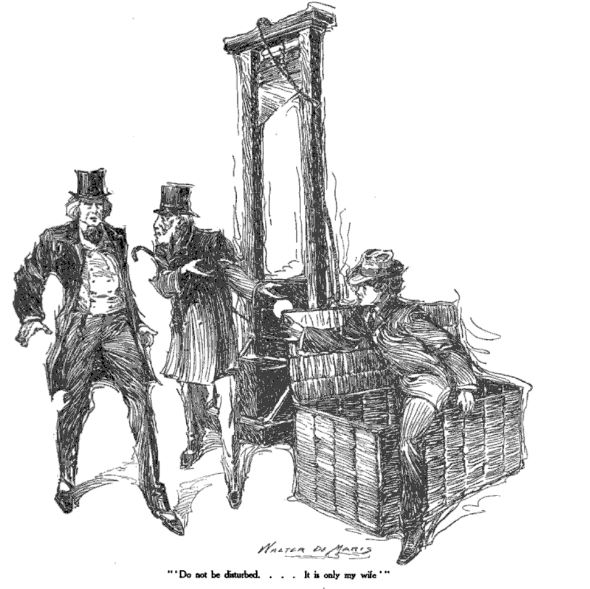

The playwright Sardou, being an authority on the guillotine in the French Revolution, desired to witness a modern execution for purposes of comparison. He was therefore present at the beheading of Troppmann; M. Deibler did the honors.

“You see I have made several improvements on the apparatus as it existed under the Terror,” he said. Sardou approached the instrument to examine the improvements, when suddenly the long wicker basket that stood beside it seemed to open of its own accord, and a young man dressed entirely in black stepped out of it. Such a theatrical apparition startled even the veteran Sardou.

“Do not be disturbed,” the executioner reassured him. Then, in an embarrassed tone, he continued: “It is only my wife! It is only in this way that she could accompany me to an execution!” Pearson’s Magazine 1905: p. 151

Monsieur de Paris valued his anonymity. His son said that his father had a favorite café where they welcomed him as “old Magnan.”

“They knew him to be Deibler. Yet there was not a waiter boy or bottle washer who would have betrayed, by look or gesture, that they knew his quality. One gesture only they refused him, and he had the delicacy not to invite it. None of his café companions shook his hand. Kansas City [MO] Star 21 April 1907: p. 2

Deibler caught a severe cold while fishing for gudgeon on the banks of the Seine. He died 6 September 1904 and was succeeded by his son Anatole, who was the last public executioner of France; after his death in 1939, subsequent executions were held inside Paris’s Santé prison instead of publicly.

Can we trust anything written about Deibler by the American press? What about that orchid? It seems so decadent, so fin de siècle, so fleurs du mal. chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

For a timeline of French executioners, see this link. There are also many other posts on this blog dealing with methods of execution such as Capital Improvements, and Professor Esclangon’s Death Mask. A search on “execution” will give you a full list.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.