“They wrapp’d his corpse in the tarry-sheet:” Burials at Sea

“They wrapp’d his corpse in the tarry-sheet” Burials at Sea

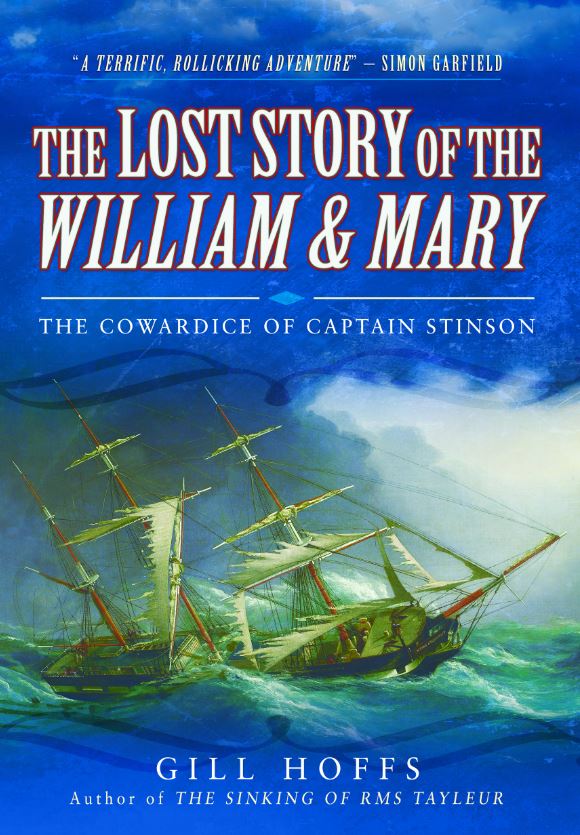

Today I’m delighted to welcome author Gill Hoffs with a guest post on the grim realities of death and burial at sea, excerpted from her new book The Lost Story of the William & Mary: The Cowardice of Captain Stinson

‘Death is at all times solemn, but never so much as at sea. Then, too, at sea, you miss a man so much. There are no new faces or new scenes to fill up the gap.’

(R. H. Dana, Two Years Before The Mast)

While researching the weird and not-very-wonderful true story of a captain and crew who attempted mass murder at sea, the issue of body disposal came up. Due in part to the inexperienced captain’s habit of prescribing bacon to passengers suffering with fever and the absence of a ship surgeon on board, fourteen emigrants died as the William & Mary crossed the Atlantic from Liverpool, England towards New Orleans in 1853. Although occasionally the bodies of people who died at sea were preserved in barrels of alcohol to allow them to be transported home, generally the deceased were given a watery grave and that was the case here – even before several of the emigrants were murdered with a hatchet as the captain and crew escaped the shipwreck. The following is excerpted from “The Lost Story of the William & Mary: The Cowardice of Captain Stinson”, out now in the UK from Pen & Sword and January elsewhere. All rights reserved.

[W]e thought we couldn’t be worse off than we war but now to our sorrow we know the differ for sure supposin’ we were dyin’ of starvation or if sickness overtuk us, we had a chance of a doctor and if he could do no good for our bodies sure the priest could for our souls and then we’d be buried along wid our own people, in the ould churchyard, with the green sod over us, instead of dying like rotten sheep thrown into a pit and the minit the breath is out of our bodies flung into the sea to be eaten up by them horrid sharks.

(Robert Whyte’s Famine Ship Diary, 1847)

Often bodies were disposed of at sea within a few hours of the death, before rigor mortis made them difficult to remove from their berth and transfer between decks and before putrefaction set in to the detriment of the remaining travellers’ health. The smell of a fresh body would also attract hungry rats from the hold and the sight of them gnawing at a loved one would only cause further distress to the emigrants. […]With any luck, the families and friends of [the fourteen who died en route to New Orleans] would have avoided the awful situation a traveller called Henry Johnson experienced, which he immortalised in a private letter to his wife in 1848,

“Anything I have read or imagined of a storm at sea was nothing to this … One poor family in the next berth to me whose father had been ill all the time of a bowel complaint I thought great pity of. He died the first night of the storm and was laid outside of his berth the ship began to roll and pitch dreadfully after a while the boxes, barrels &c began to roll from one side to the other the men at the helm were thrown from the wheel and the ship became almost unmanageable at this time I was pitched right into the corpse, the poor mother and two daughters were thrown on top of us and there corpse, boxes, barrels, women and children all in one mess were knocked from side to side for about fifteen minutes pleasant that wasn’t it. Jane Dear Shortly after the ship got righted and the captain came down we sowed the body up took it on deck and amid the raging of the storm he read the funeral service for the dead and pitched him overboard.”

While mourning and body disposal was highly ritualised on land at that time, at sea it very much depended on how a person died, who was left on board to grieve for them and the culture of the ship. One passenger, according to the Glasgow Herald of 5 May 1854, while giving evidence about his journey on the cholera-ridden Fingal to a committee regarding emigrant ships, said ‘I heard the sailors refuse to throw some of the bodies overboard; they were afraid of touching them and I consider they objected because they were not paid. In one case the body was not sewn up in canvas before it was thrown overboard; the captain said, “We are not bound to do it; it is only according to courtesy”.’

It was common practice for a body to be washed down by the deceased’s family, friends or berth-mates, then sewn tightly into their hammock or bedding, or a scrap of sailcloth. As one man told the Waterford Chronicle of 3 September 1831, ‘it was customary to run the needle in the last stitch through the nose of the corpse’, partly to check they were dead but also to help keep the corpse in place within the shroud bundle. They often remained in the outfit they died in, although sometimes layers were stripped off and given to relatives or sold to raise money for any dependents they may have had. Heavy items such as cannon shot were placed at their feet within the shroud, or sometimes tied on, in order to sink the corpse and spare their fellow passengers the unenviable sight of the body being picked at by scavengers including sharks. Sometimes this went wrong, as ‘an orphan girl’ reported to the Dublin Evening Post of 24 September 1839, when the unfortunate Mr Lewis died of fever.

“[A]t that impressive sentence in the form of burial at sea, ‘We commit our brother to the deep!’ [his body] was gently lowered into its ocean tomb. Never shall I forget the sound of splashing waters, as, for an instant, the ingulfing wave closed over his remains!

‘Oh! that sound did knock

Against my very heart.’

The coffin, encased in its shroud-like hammock, rose again almost immediately; the end of the hammock having become unfastened and the weights which had been enclosed, escaping, the wind getting under the canvas acted as a sail and the body was slowly borne down the current away from us … I remained on deck straining my eyes to watch, as it floated on its course, the last narrow home of him who had, indeed, been my friend; till, nearly blinded by my tears and the distance that was gradually placed between the vessel and the object of my gaze, it became like a speck upon the waters and I saw it no more!”

There are accounts of emigrant ships ravaged by disease having their dead removed with boat hooks and ‘stacked like cordwood’ in quarantine stations, ready for disposal, but although the William and Mary suffered a comparatively high number of deaths for the route and season, there were enough passengers left alive for humanity to prevail. Emigrants were at more risk of catching contagious diseases such as dysentery, cholera or smallpox at sea than on land. Generally at that time mortality rates on ships were approximately 2 per cent, but in bad years they could be 10 per cent or even 25 per cent and above. It is only surprising given the conditions on board emigrant ships that this figure wasn’t higher.

Mr J. Custis, a surgeon from Dublin, worked on six emigrant ships and wrote in the Mona’s Herald, 1857:

“… take all the stews [brothels] of Liverpool, concentrate in a given space the acts and deeds done in all for one year and they would scarcely equal in atrocity the amount of crime committed in one emigrant ship during a single voyage … I have been engaged during the worst years of famine in Ireland; I have witnessed the deaths of hundreds from want; I have seen the inmates of a workhouse carried by hundreds weekly through its gates to be thrown unshrouded and coffinless into a pit filled with quicklime … and revolting to the feelings as all this was, it was not half so shocking as what I subsequently witnessed on board the very first emigrant ship I ever sailed in. In the former instance every exertion was made to save life, in the latter to destroy it.”

Charles Dickens is quoted in Robert Whyte’s 1847 Famine Ship Diary as saying, ‘sickness of adults and deaths of children on the passage are matters of the very commonest occurrence’ and they were, but this didn’t inure their loved ones to their loss, though many found strength in a strong belief in the afterlife. William Watkins, whose account of emigration was included in the Hereford Times of 12 November 1853, was deeply affected.

“[W]e have grim death at work and afterwards the awfully solemn burials. Death at any time is an awful termination to this dream of life; but at sea, it is most to be dreaded. Your mate may be well to-day – to-morrow death may strike him; and in a few short hours the body is placed upon a plank – the burial service is read, a lift, a roll and then you hear a hollow sounding plunge and the deep seas receive the body of those you may have loved dearly. The waves continue their onward course and your friend is gone for ever. There is something peculiarly horrifying in the sound of a body being thrown into the sea – a sound that it would be most impossible to describe, but one that causes the frame to vibrate and strikes terror to the soul, calculated to make us reflect upon our past and present life, so as to prepare for that awful change, which must inevitably come to all of us.”

Sometimes the sheer awfulness of a voyage provided a distraction and enabled them to carry on as they had no choice but to do so or die themselves. But different families coped with their grief in different ways and for some travellers the burial at sea of a shipmate was little more than an interesting spectacle. One emigrant’s letter, published in the Inverness Courier on 17 February 1853, mentions the death of a child on board.

“It was in a canvas bag and laid on a board and one of the sailors held the board while the doctor read – and the first mate gave notice to the sailor and he lifted up one end of the board and shot it into the sea. I got into the rigging to see it go into the water. But very bad order was kept. A funeral at sea has very little effect even on the friends, for the corpse is thrown overboard and no more notice is taken.”

One man described the problem with burial at sea to the Royal Cornwall Gazette of 9 September 1853, saying ‘It can matter little to the dead where their bodies repose; but the idea is a painful one, that over the remains of those buried at sea, no tears of affection can flow, or visits of love be paid, to their last resting place.’

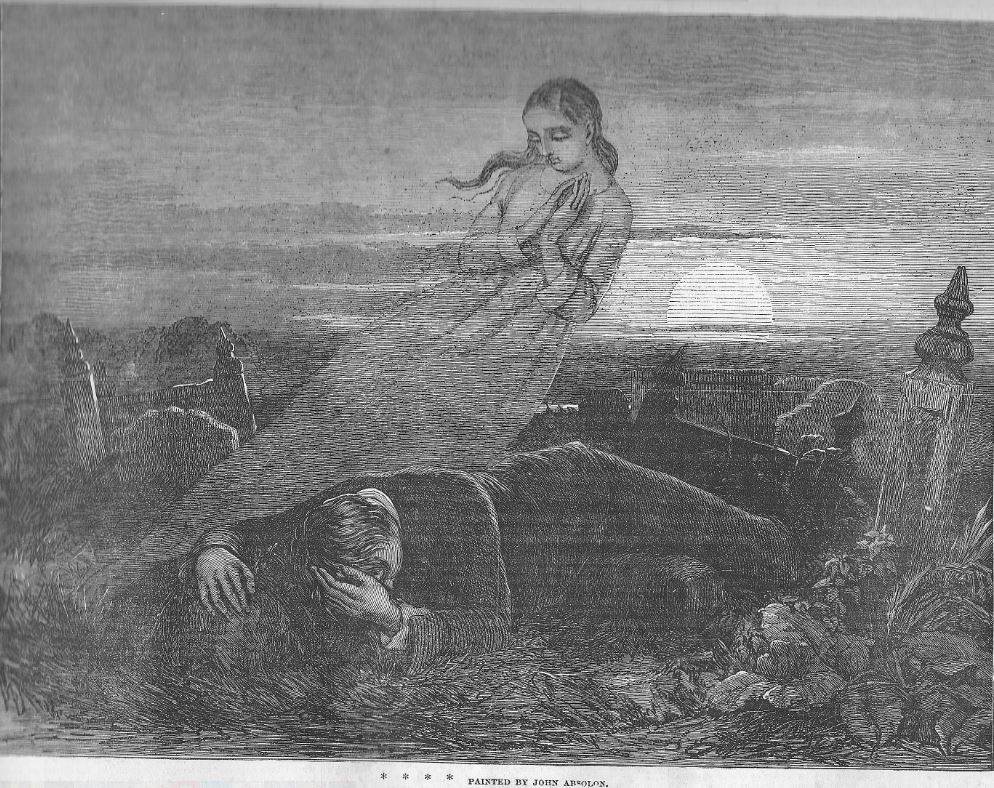

A maudlin and sentimental view, but a very Victorian one, with the emphasis on the plight of those left behind. The lack of a physical focal point for mourning may have been a blessing in disguise for some families, though it might not have seemed so at the time. The emphasis on structured grief and sentimentalised bereavement in Victorian society – and high mortality rates – sometimes led to tragedy, such as the one that befell the Mead family according to the Worcester Journal of 8 July 1852:

“[S]ix months ago [she] buried a favourite child, for whose death she was inconsolable. She constantly went to Kensal Green Cemetery, threw herself upon the child’s grave and wept for hours. She would then gather the flowers that grew over the grave, bring them home and leave them in water till they decayed, when she would eat them. Day after day she thus indulged her grief; and upon returning home on the 15th ult. after visiting the child’s grave as usual, she told her husband, children and friends, that she had only a few days to live. She then had the mourning made for her children, which they were to wear for her; and having directed her husband to have the dead bell tolled for her, refused all medical aid, nourishment and consolation, until Friday week, when she fell a lifeless corpse from her chair to the ground. Mr. Obre, surgeon, performed the autopsy and found that the deceased died of disease of the heart, produced by deep affliction.”

What the less-favoured children felt about this is not revealed.

[…]

Mourning traditions on land had little merit when those stricken with grief were at sea. A poem by ‘M.J.S.’ included in the Roscommon Journal of 11 July 1835 encapsulates some of the attitudes and rituals common in the early to mid-1800s.

“… they wrapp’d his corpse in the tarry-sheet,

To the dead as Araby’s spices sweet,

And prepared him to seek the depths below,

Where waves ne’er beat, nor tempests blow.

No steeds with their nodding plumes come here,

No sabled hearses, no coffined bier,

To bear with parade and pomp away

The dead to sleep with its kindred clay.

But the little group, a silent few – His companions mixed with the hardy crew,

Stood thoughtful around, till a prayer was said

O’er the corpse of the deaf, unconscious dead,

Then they bore his remains to the vessel’s side,

And committed them to the dark blue tide:

One sullen plunge and the scene was o’er,

The wave roll’d on as it roll’d before!

In that classical sea, whose azure vies

With the green of its shore and the blue of its skies;

In some pearly cave, in some coral cell,

Oh! the dead shall sleep as sweetly as well

As if shrined in the pomp of Parisian tombs,

When the east & the south breathe their rich perfumes.

Nor forgotten shall be the humblest one,

Though he sleep in the watery waste alone;

When the trump of the angel sounds with dread,

And the sea, like the earth, shall yield his dead.”

See “The Lost Story of the William & Mary: The Cowardice of Captain Stinson” (Pen & Sword, 2016) for more about how 200 Victorians came back from the dead, or get in touch with Gill at gillhoffs@hotmail.co.uk or find her as @GillHoffs on twitter. http://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/The-Lost-Story-of-the-William-and-Mary-Hardback/p/12290

Many thanks, Gill!