A Post-Mortem Room Ghost

A short time ago, I promised my readers an occasional series of “Little Visits to the Great Morgues of Europe,” which started with the morgue at the Monastery of the Mount St. Bernard in the Alps. Further morgues will be profiled, but in scouring the journals of the past for crowd-pleasing details of maggots and decomposition discerning readers demand, I got distracted by this account from a hospital morgue in Dublin, Ireland. I pride myself on not being rattled by the average ghost story, but this one actually brought me up rather short.

A Post-Mortem Room Ghost

[The subjoined is a narrative of the experience of Dr. B__. It has been transcribed for the benefit of readers of the Occult Review by Dr. J.H. Power, the record having been previously checked and its accuracy confirmed by Dr. B__.]

See me, at the time the following episode happened, a medical student at a hospital in Dublin. I was not quite a novice, being in the third year of my course. I was in the pink of health, and with the happy irresponsibility of the golden age of twenty-one years. In truth I was a bit of a lad, never happier than when I was playing pranks on citizens both offensive and inoffensive. All the same I was never in serious trouble, for up till then a bottle had never touched my lips, and my little differences with the police were the outcome of friendly religious and political fights.

I mention these few facts about myself as a proof that I was, for my age, a normal Irishman, with vague ideals, content to take life as it came, never troubling about anything practical save what the moment gave, and loyally hating the Government.

While I was taking my turn as resident clinical clerk at the hospital, a young man was brought in one morning with a temperature of 106°, a condition known as hyperpyrexia. No cause was found for his high fever at the time, though later it was discovered that he had been suffering from peritonitis, and, for some reason that I have forgotten, he was sent to the wing of the hospital that was reserved for infectious cases. I saw this patient that morning in company with the physician under whose care he was placed, but not again during the day.

As clinical clerk it was my duty to go round the wards during the night and inspect the patients, reporting to the house surgeon or the house physician if I found anything that I thought needed his attention.

About midnight came my visit to the fever wing. This was built separate from the rest of the building, and I had to go some twenty yards in the open air to get to it. The side door of the hospital, through which I left, was kept locked, and on opening it, I found that snow was falling. Turning up the collar of my jacket, I started to make a dash for my destination, when I saw coming towards me through the snow the hyperpyrexia patient who had been brought in the previous morning. He was clad—so far as my impression went, and I confess that I did not think much of how he was clad, and, of course, the light did not favour a casual glance—in the night-shirt and red flannel jacket that were used in the wards.

Stopping short, I waited for him to come up, thinking that he was walking in his sleep; and having some notion that a somnambulist should not be awakened suddenly, I stood back by one of the buttresses that supported the wall of the hospital. As I glanced round, fully expecting to see a nurse running from the fever wing in pursuit, he passed me in the direction of the side door of the hospital. No nurse was in sight, and on looking again for the patient, nobody was to be seen. The man had gone—nowhere, for I had locked the side door on leaving the hospital, on the right of the side door was an unscalable wall, and immediately opposite this side door was the morgue, the door of which was fastened with a Yale lock of which I had the key. He could not have passed back the way he had come, or I should have seen him.

Then I felt that kind of chilliness down the back which is not caused by cold, for I realized that I had come across something a trifle out of the ordinary.

“There’s no fun in snow,” said I to myself, and made a bolt for the fever wing.

On entering the ward, I saw the night-nurse sitting in a chair asleep, with a book in her lap. I went to the bed of the hyperpyrexia man, and, as I expected, found him dead, the condition of the body showing that he had died but a few minutes before. I next went to the slate on which the night nurse wrote reports of patients, and found that opposite the number of the hyperpyrexia patient’s bed, she had noted that his temperature had fallen and he was better, not more than a quarter of an hour previously.

I then went to the nurse. She woke with a start, and exclaimed, “My God, you did give me a fright. I thought Sister had come in and struck me on the mouth with a clothes-brush.”

“How is No. 19?” I asked.

“Oh, much better,” she replied, “his temperature has dropped.”

“Should you be surprised to hear that he was dead?” I answered.

She was much upset, but still she was not to blame, and as there was no more to be done, the night-porters were sent for, and the body taken to the morgue.

At 9.30 a.m. the pathologist gave demonstrations in the morgue, and by that hour bodies had to be prepared for him by the clinical clerks. This rather nauseous task fell to my share during the week, and about 2 a.m. I decided that I would get on with the preparation of the body of the hyperpyrexia man.

I own that the job had no attractions for me. I was feeling more upset by what I had seen in the snow than I would have believed possible. Up to that time I had laughed at the idea of being afraid of anything uncanny, and would have gone out of my way to meet a ghost. Besides, our morgue was not a very cheerful place. No post-mortem room that ever I came across has many pretensions to liveliness, but in addition the gas burner in our morgue was faulty, and had a way of slowly and silently allowing a jet of gas to grow up to a flare, and then cutting it off till the flame faded to a minute spark. However I would not allow to myself that I was so badly scared as not to be able to do what there was to be done, so I went down to the morgue.

I had to hold myself well together as I put the key in the lock. . . . Then with another effort I pushed the door open.

The gas had not been turned out by the porter, and by its uncertain light I saw the corpse lying on the table, covered with a sheet, with the feet towards me, and facing me, standing at the head, close against the table was the Figure of the man himself, watching.

I must have been a plucky youngster in those days, for even then, frightened as I was, I did not give in. I remember that I did not look straight at the Watcher, but kept my eyes slightly averted. I had in my mind the notion that he could not, or would, not blame me for what I was about to do to his body, if I did not know he was there, and so I pretended that I did not see him. Why I should have thought that he would be so easily deceived I cannot tell, but one has strange notions at trying times.

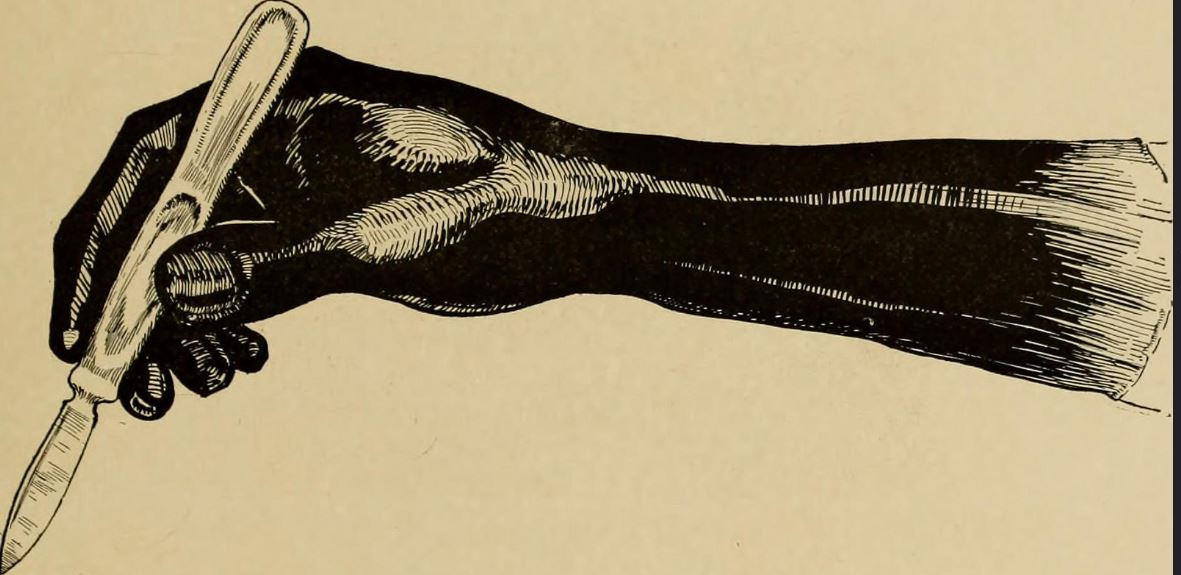

Strive as I would, however, I could not bring myself to go through the process of prosection in the usual way. I cannot be certain now, but I fancy I had some idea of finding if the man was really dead, and making a wound to test the matter. Still taking no notice of the Figure, I gave the table a pull, and ran it on its castors till it was quite near the gas. The Watcher at the head moved with it. Then, instead of uncovering the body from the head downwards, as I should ordinarily have done, I took hold of the sheet and threw it upwards from the feet. The Watcher at the head did not move. Then, greatly daring, I took the knife in my hand, and made as if to pierce the leg of the corpse. Instantly the Watcher made a motion with his hand, and…

I remember no more till about 9 a.m. the next morning, when the other clinical clerk came to the room and found me asleep on the floor. I think it likely that the mental strain had made me lose consciousness, but I did not feel like telling anybody about it all, and said that I had been tired and had lain down there and fallen asleep. We must have been a happy-go-lucky lot, for the fact of my having chosen the cold stone floor of the morgue as a resting place excited no particular remark from him. I caught a bad cold, and another man did the prosection, but I told nobody what had happened on that dreadful night till many a day later.

The Occult Magazine July 1918: p. 32-35

Taking up my Relentlessly Informative syringe, the fever ward patients were dressed in red flannel jackets because red flannel was not only warm, but was believed to protect the chest and throat—it was often called “medicated flannel.” An 1861 medical journal suggests also that the toxic poison-sumac dyes in some red flannel served as “a very excellent, gentle counter-irritant,” counter-irritants being thought useful in “drawing out” disease. It obviously had no salutary effect on the patient with peritonitis.

This story will be found in my upcoming book When the Banshee Howls.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.