Veto Goes Mad

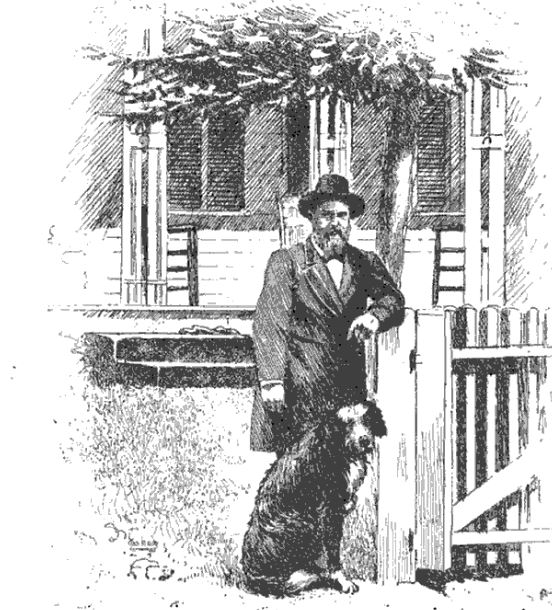

Veto Goes Mad. General Garfield and Veto at Lawnfield, Mentor, Ohio.

It was on 19 September 1881 that President James A. Garfield, shot by Charles Guiteau on 2 July, died of gangrene from the probing, septic fingers of the physicians. The entire country mourned, including the President’s favorite black Newfoundland dog, Veto, left behind on the family farm in Mentor, Ohio.

I promise a Fortean twist at the end, but indulge me as I share some of the heart-warming profiles of the presidential pet that appeared in the press of the 1880s, like this one, which was published in the children’s magazine, St Nicholas:

GENERAL GARFIELD’S DOG.

In the summer of 1880, when the first delegation of enthusiastic politicians came trooping up from the Mentor station through the lane that led to “Lawnfield,” in order to congratulate General James A. Garfield on his nomination for the Presidency, there was one member of the Garfield household who met the well-meaning but noisy strangers with an air of astonishment and disapproval, and, as they neared the house, disputed further approach with menacing voice.

This was “Veto,” General Garfield’s big Newfoundland dog; and not until his master had called to him that it was “all right,” and that he must be quiet, did he cease hostile demonstrations.

After that, whenever delegations came — and they were of daily occurrence — Veto walked around among the visitors, looking grave and sometimes uneasy, but usually peaceful. General Garfield was very fond of large, noble-looking dogs. Veto was a puppy when given to him, but in two years’ time had grown to be an immense fellow, and devotedly attached to his master. He was named in honor of President Hayes’s veto of a certain bill in the spring of 1879.

The bill was one for abolishing the office of marshal at elections. It did not meet with the President’s approval, and he returned it to Congress unsigned,— an action which greatly pleased General Garfield, and suggested the name for his dog.

Although quiet, as he had been bidden, Veto was never reconciled to the public’s invasion of the Mentor farm. He was a dog of great dignity, and could not but feel resentment at the familiarity of the strangers who, on the strength of their political prominence, overran his master’s fields, spoiled the fruit-trees, peered into the barns and poultry yard, and were altogether over-curious and intrusive. He had been told that it was “all right”; but these actions by day, and the torchlights and hurrahing by night, wore on his spirits and temper. This evident unfitness for public life caused a final separation from his beloved master; for when, in the following spring, the family moved to Washington to begin residence at the White House, they thought it was not best to take Veto with them, so he was left behind in Mentor.

Poor fellow! all his doubts and fears for the safety and peace of him he loved and guarded were indeed well-founded. That first invasion of Lawnfield was but the beginning of what was to end in great calamity and bitter sorrow. Veto never saw his master again.

After the death of General Garfield, Veto was taken to Cleveland, O., where he spent his remaining days in the family of J. H. Hardy — a gentleman well known in that city.

Several anecdotes are related by Mr. Hardy which prove the dog’s great intelligence. He slept in the barn, and seemed to consider himself responsible for the proper behavior of the horses, and the safety of everything about the barn. No one not belonging to the family was allowed even to touch any article in it. Veto’s low thunder of remonstrance or dissent quickly brought the curious or meddlesome to terms.

One night he barked loudly and incessantly. Then, as this alarm signal passed unnoticed, he howled until Mr. Hardy was forced to dress and go to the barn, where he found a valuable horse loose and on a rampage. Veto had succeeded in seizing the halter, and there he stood with the end in his mouth, while the horse, disappointed of his frolic and his expectation of unlimited oats, was vainly jerking and plunging to get away.

Another time, upon returning late at night from a county fair, the family heard Veto—who was shut up in the barn — howling and scratching frantically at the door. When it was opened, he rushed directly to another barn some rods away, belonging to and very near a house occupied by a large family, who all were in bed and asleep. He scratched at the door of this barn, keeping up at the same time his dismal howl, and paying no attention to the repeated calls and commands to “come back and behave ” himself. Just as force was to be used to quiet him, a bright tongue of flame shot up through the roof of the barn, and, almost in an instant, the whole structure was in a blaze. Before the fire department reached the spot the barn was consumed, and the house was saved from destruction only through heroic efforts of the neighbors.

And so Veto’s quick scent and wonderful sagacity in, as we must believe, giving the alarm, not only saved the house, but probably averted serious loss of life.

DOGS OF NOTED AMERICANS. PART 1, Gertrude Van R. Wickham, St. Nicholas, Volume 15, Part 2: pp. 595-596

Although I don’t know if the account is accurate, it was reported in the Chicago Tribune that Garfield had done a favor for an African-American servant of General Winfield Scott, who bred horses and dogs. After Scott’s death, the servant continued breeding dogs and in thanks presented a Newfoundland puppy to Garfield. Veto was Garfield’s constant companion on his tours of inspection around the farm and he was indulgent to the big dog.

One night, after a hard day’s work, a few of us were gathered in his library, and we were talking of various subjects of mutual interest. Finally I remarked to him that I had that day received a letter from one of his old pupils who is now in the West. I said to him. ‘Myra wonders if you think she is married. She says you address her as Madame.’ ‘Let me see her letter,” he said. I showed it to him, and after reading it, he said: ‘Oh, the dear old girl! One of my clerks has made a mistake and offended her, I fear. But I will settle that.’ So he took his pen, weary as he was, and began to write her a letter of explanation. He had written nearly the whole of the first page, when ‘Veto,’ who had been standing by wagging his tail for some time and trying to get some attention from his master, at length became impatient and placed his big, dirty paw upon the page still wet with the ink, and made an unreadable and unsightly scrawl of the whole. ‘O you good-for-nothing old fellow!’ said the general, patting the dog’s head, ‘you have made me a good deal of trouble and labor by your over-familiarity.’ He then quietly tore up the sheet and began his letter over again.” Wheeling [WV] Register 5 April 1881: p. 3

Newfoundlands are sociable dogs and Veto did not take kindly to a slight.

It is unjust to mention the other animals on Gen. Garfield’s farm and say nothing of his big black Newfoundland dog, “Veto.” He is a very kind and intelligent fellow, and seems to share in the genial and hospitable spirit which pervades the premises. He expects recognition from every visitor. Going into the General’s office, once, after a few days absence, I greeted the gentlemen who were there, but did not speak to Veto. He looked at me expectantly from the opposite side of the room for a minute or two, and when, I still failed to speak to him, he saluted me with a bow-wow-wow that was perfectly comical in its peculiar tone of reproof, and then sprang across the room and laid his head on my knee for the customary patting. Somerset [OH] Press 30 December 1880: p. 2

Veto was a favorite with the Garfield children and he was happy on the farm at Mentor. Why was he sent away? I found this odd, minor, Fortean anecdote which suggests one explanation for his exile. I have not seen this story anywhere else in the presidential pet literature, or, indeed, anywhere except this one newspaper.

GOING BACK HOME.

Mrs. Garfield will spend the summer on the old homestead at Mentor. The place will have probably never seem [sic] like home to her. The little telegraph office, which has been immortalized in story and magazine engravings, still stands, and the place has not changed in its general aspect, but the life of it is gone. The big dog Veto who used to take it upon himself to meet incoming visitors, and who was made famous in print during the presidential campaign, is also gone. It is a strange fact that the faithful animal showed unmistakable evidence of derangement about the time that Garfield died. One sultry Sunday he came into the house with bloodshot eyes, and acted wholly unlike himself. The young Garfield boys were at Mentor then, and, fearing that the dog would bite them, Rudolph went after a gun to kill him. By the merest accident the dog escaped death, and the next day he was given to a farmer in Mayfield who took him away at once. Veto never came back to his old home, and is still on a farm in Mayfield. He recovered from his symptoms of madness, if madness it was, but he never acted like himself again. Dover Weekly Argus [Canal Dover OH] 29 June 1882: p. 1

If the sagacious canine stories told of his time with the Hardy family are true, he could not have had rabies. Of course, Newfoundlands are subject to heat stroke, so perhaps the “sultry Sunday,” was the culprit, rather than some psychic link between his lost master and himself.

Any other reports of Veto’s madness when Garfield died? Or, since it is told after the fact, is this just barking?

chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Previously I wrote about a child’s vision of Garfield among the angels and of the gruesome post-mortem career of Charles Guiteau’s face.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.