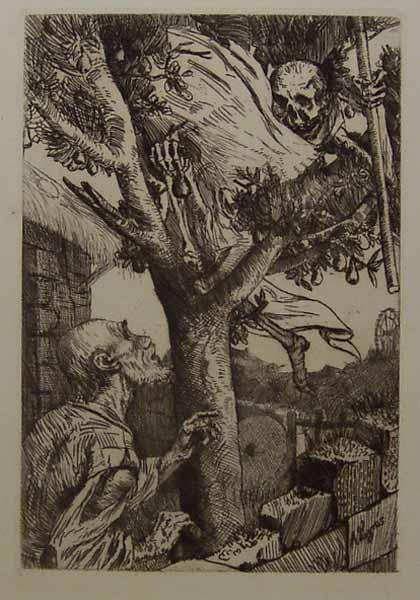

Death in the Mango Tree

Death in the Mango Tree Death in the Pear Tree, Alphonse Legros, 1870 http://manchesterartgallery.org/collections/search/collection/?id=1882.92

Tomorrow is Earth Day and while I’m mixed about having a minor forest in my back yard (mostly blocks the neighbors’ line of sight; whispers in a high wind) if you read enough of Elliott O’Donnell on “Trees of Ghostly Dread,” “Sylvan Horrors,” and “vagrarians,” (whatever they are–did he made up the latter word?) you will be reluctant to turn your back on that ash tree–surely it is closer to the house than it was yesterday?

Arboreal entities are one of O’Donnell’s major obsessions–second or third only to pig-faced elementals and misogyny. I wonder if his mother, while carrying him, was frightened by an Ent?

Here is O’Donnell on spirit-haunted trees. The Devil is in the mangoes…

Trees are, I believe, frequently haunted by spirits that suggest crime. I have no doubt that numbers of people have hanged themselves on the same tree in just the same way as countless people have committed suicide by jumping over certain bridges. Why? For the very simple reason that hovering about these bridges are influences antagonistic to the human race, spirits whose chief and fiendish delight is to breathe thoughts of self-destruction into the brains of passers-by. I once heard of a man, medically pronounced sane, who frequently complained that he was tormented by a voice whispering in his ear, “Shoot yourself! Shoot yourself!”—advice which he eventually found himself bound to follow. And of a man, likewise stated to be sane, who journeyed a considerable distance to jump over a notorious bridge because he was for ever being haunted by the phantasm of a weirdly beautiful woman who told him to do so. If bridges have their attendant sinister spirits, so undoubtedly have trees—spirits ever anxious to entice within the magnetic circle of their baleful influence anyone of the human race.

Many tales of trees being haunted in this way have come to me from India and the East. I quoted one in my Ghostly Phenomena, and the following was told me by a lady whom I met recently, when on a visit to my wife’s relations in the Midlands.

“I was riding with my husband along a very lonely mountain road in Assam,” my informant began, “when I suddenly discovered I had lost my silk scarf, which happened to be a rather costly one. I had a pretty shrewd idea whereabouts I might have dropped it, and, on mentioning the fact to my husband, he at once turned and rode back to look for it. Being armed, I did not feel at all nervous at being left alone, especially as there had been no cases, for many years, of assault on a European in our district ; but, seeing a big mango tree standing quite by itself a few yards from the road, I turned my horse’s head with the intention of riding up to it and picking some of its fruit. To my great annoyance, however, the beast refused to go; moreover, although at all times most docile, it now reared, and kicked, and showed unmistakable signs of fright.

“I speedily came to the conclusion that my horse was aware of the presence of something—probably a wild beast—I could not see myself, and I at once dismounted, and tethering the shivering animal to a boulder, advanced cautiously, revolver in hand,to the tree. At every step I took, I expected the spring of a panther or some other beast of prey; but, being afraid of nothing but a tiger—and there were none, thank God! in that immediate neighbourhood— I went boldly on. On nearing the tree, I noticed that the soil under the branches was singularly dark, as if scorched and blackened by a fire, and that the atmosphere around it had suddenly grown very cold and dreary. To my disappointment there was no fruit, and I was coming away in disgust, when I caught sight of a queer-looking thing just over my head and half-hidden by the foliage. I parted the leaves asunder with my whip and looked up at it. My blood froze.

“The thing was nothing human. It had a long, grey, nude body, shaped like that of a man, only with abnormally long arms and legs, and very long and crooked fingers. Its head was flat and rectangular, without any features saving a pair of long and heavy lidded, light eyes, that were fixed on mine with an expression of hellish glee. For some seconds I was too appalled even to think, and then the most mad desire to kill myself surged through me. I raised my revolver, and was in the act of placing it to my forehead, when a loud shout from behind startled me. It was my husband. He had found my scarf, and, hurrying back, had arrived just in time to see me raise the revolver—strange to relate—at him! In a few words I explained to him what had happened, and we examined the tree together. But there were no signs of the terrifying phenomenon—it had completely vanished. Though my husband declared that I must have been dreaming, I noticed he looked singularly grave, and, on our return home, he begged me never to go near the tree again. I asked him if he had had any idea it was haunted, and he said: ‘No! but I know there are such trees. Ask Dingan.’

Dingan was one of our native servants—the one we respected most, as he had been with my husband for nearly twelve years —ever since, in fact, he had settled in Assam. ‘The mango tree, mem-sahib!’ Dingan exclaimed, when I approached him on the subject, ‘the mango tree on the Yuka Road, just before you get to the bridge over the river? I know it well. We call it “the devil tree,” mem-sahib. No other tree will grow near it. There is a spirit peculiar to certain trees that lives in its branches, and persuades anyone who ventures within a few feet of it, either to kill themselves, or to kill other people. I have seen three men from this village alone, hanging to its accursed branches; they were left there till the ropes rotted and the jackals bore them off to the jungles. Three suicides have I seen, and three murders—two were women, strangers in these parts, and they were both lying within the shadow of the mango’s trunk, with the backs of their heads broken in like eggs! It is a thrice-accursed tree, mem-sahib.’ Needless to say, I agreed with Dingan, and in future gave the mango a wide berth.”

Byways of Ghost-Land, Elliott O’Donnell, 1911: p. 63-67

Not, I think, a tree to hug.

Other deadly trees? I’ve written before of the ghost in the hollow tree of Pogues Run, Indiana, with its neighboring rolling bogey.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.