Magical Folk and Munes

Magical Folk and Munes. Magical Folk – British & Irish Fairies, just published!

Today I’m delighted to announce the publication of the new book Magical Folk: British and Irish Fairies: 500 AD to the Present, by Simon Young and Ceri Houlbrook, an outstanding collection from a multitude of fairy experts, displaying the full range of fairy types and beliefs in Britain and Ireland. There are also three chapters on European emigrant fairies in the New World.

First, the contents and contributors:

Magical Folk: British and Irish Fairies, 500 AD to the Present (Gibson Square 2017), (ed) Simon Young and Ceri Houlbrook. 1 ‘Fairy Queens and Pharisees: Sussex’, Jacqueline Simpson; 2 ‘Pucks and Lights: Worcestershire’ Pollyanna Jones; 3 ‘Pixies and Pixy Rocks: Devon’, Mark Norman and Jo Hickey-Hall; 4 ‘Fairy Magic and the Cottingley Photographs: Yorkshire’, Richard Sugg;5 ‘Fairy Barrows and Cunning Folk: Dorset’, Jeremy Harte; 6 ‘Fairy Holes and Fairy Butter: Cumbria’, Simon Young; 7 ‘The Sídhe and Fairy Forts: Ireland’, Jenny Butler; 8 ‘The Seelie and Unseelie Courts: Scotland’, Ceri Houlbrook; 9 ‘Trows and Trowie Wives: Orkney and Shetland’, Laura Coulson; 10 ‘The Fair Folk and Enchanters: Wales’, Richard Suggett; 11 ‘Pouques and the Faiteaux: Channel Islands’, Francesca Bihet; 12 ‘George Waldron and the Good People: Isle of Man’, Stephen Miller; 13 ‘Piskies and Knockers: Cornwall’, Ronald M. James; 14 ‘Puritans and Pukwudgies: New England’, Peter Muise; 15 ‘Fairy Bread and Fairy Squalls: Atlantic Canada’, Simon Young; 16 ‘Banshees and Changelings: Irish America’, Chris Woodyard

These are the Good People with a vengeance, as the blurb makes crystal clear:

Magical Folk is the first major publication on British and Irish fairies since 1978 and stars not the nauseating tutu-wearing, sugar plum fairies of Disney, but the terrifying blood-sucking, baby-stealing, bed-hopping fairies of tradition. We have Cumbrian fairies blowing up railway lines, Dorset fairies going horse rustling, and a fairy (actually a mistreated wife) being burnt alive in Ireland in 1895. Fairies are back and they are bad…’

I contributed the chapter on Irish fairies in America and I’m thrilled to be in the company of so many extraordinary scholars. I’ll share a review very soon, but fae aficionados will not want to wait!

Considering its melting-pot designation, the United States has a curious fairy deficit and there has always been debate about whether the People of Peace arrived with Irish (or any other) immigrants. As an engineer of my acquaintance put it: “If fairies are real, why would they come to America? And if fairies are not real, why would they not come?”

Fair questions, both: why leave the Dear Green Place? (Unless the fairies, too, were suffering the horrors of the Famine.) And if carried in the collective imagination of the emigrants, the Gentry ought to have manifested wherever their hosts were found. But that is what my chapter is about: Did the Fair Folk come to America? That and a fairy abduction in Iowa.

One American artist felt the lack of American fairy lore keenly and was inspired to do something about it. This was Frederick Judd Waugh [1861-1940], son of a Philadelphia portrait painter, who, after finishing his artistic training, moved to the island of Sark in the English Channel, where he painted seascapes. He was very good at it, in a Royal Academy sort of way and, during the First World War, used his experience to design ship camouflage for the U.S. Navy. But he chafed at the conventionalities of his career and longed for something to stir the imagination. He found the answer in tree roots and bits of driftwood.

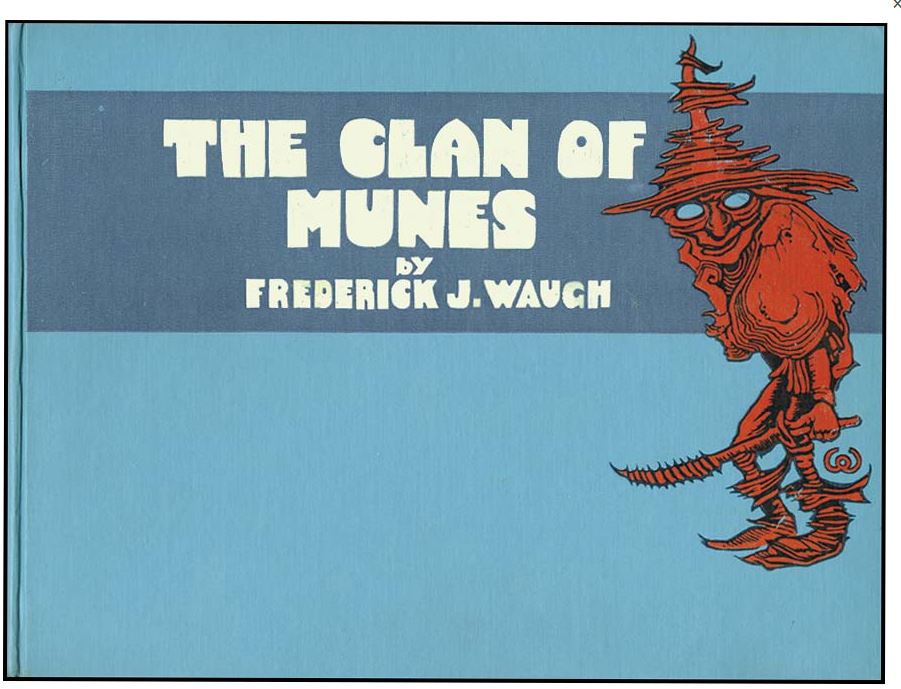

Magical Folk and Munes. Cover of The Clan of the Munes,” with a rather orc-like Mune. https://www.alephbet.com/pages/books/37326/frederick-j-waugh/clan-of-munes

REAL AMERICAN FAIRIES AT LAST

Queer Creatures Which a Noted Painter Sees in Tree Roots and Bits of Driftwood—And How the Indian “Totem Poles” Inspired Their Creation.

What is a Mune? A Mune, says Frederick J. Waugh, is an American Fairy. He discovered the Munes, drew their portraits and has written their family history.

Mr. Waugh is best known for his powerful marine paintings, although he has turned his hand to sculpture, illustration, and was even an artist for one of the great English weeklies during the Boer war. But he feels that his greatest gift to his fellow countrymen is the clan of Munes, or tribe of American Fairies. He feels that they fill a long-felt want.

As the Germans have their Gnomes, the Irish their Leprechauns, the French their fays and goblins and the English their sprites and elves, so now we Americans have, thanks to Mr. Waugh, fairies of our own, which he calls Munes.

Magical Folk and Munes: Two of Mr. Waugh’s fairies or Munes, photographed from life.

The Munes were originally just old roots and stumps and odds and ends of driftwood, but Mr. Waugh, taking inspiration from his great collection of Indian Totem Poles, determined to make them live. By incantation and the magic power of his Totem Poles he succeeded at last in doing so.

These pieces of wood, which you will find bobbing along the seashore or hiding in the woods under fallen trees, are the Munes; they are alive and full of enterprise, and if you examine them it is easy to see how they resemble the Totem Poles whose spirits gave them life.

According to Mr. Waugh, this clan of American Fairies is very thriving and active. He has written a kind of family history of a good many of their adventures, and drawn pictures of many important events among them.

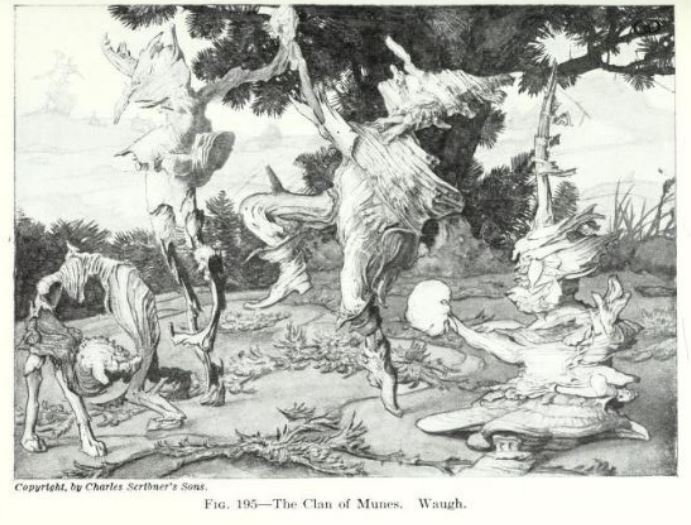

Charles Scribner’s Sons have published this amusing contribution to American imaginative folk-lore under the title “The Clan of Munes.”

The pictures reproduced on this page are from that book, and give a good idea of what our newly-discovered American Fairies look like. Their resemblance to the Indian Totem Poles—and what is more typically American than a Totem Pole?—is plain enough, and yet it is also plain enough that they are just bits of weathered wood.

“The inspiration came to me two years ago,” said Mr. Waugh. “I brought back several boxes of curiously shaped bits of driftwood and roots when I returned from my Summer outing. From them I worked out our National Fairies in book form, and hope it may give others half as much pleasure in reading about them as I had in their creation.” The New Orleans [LA] Item 17 December 1916: Magazine Section

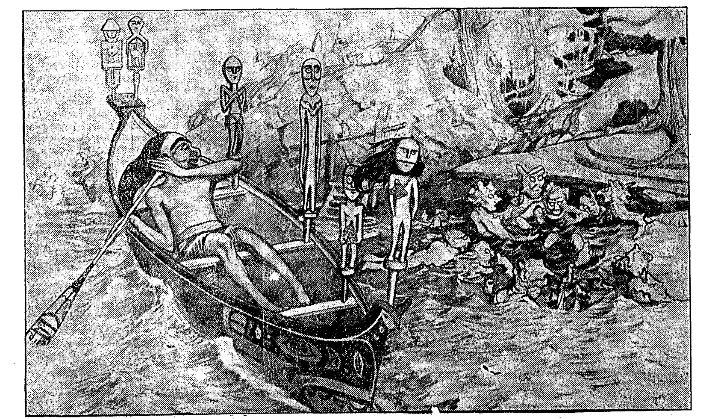

Magical Folk and Munes The King of the Munes Travels Through His Kingdom in Defiance of the Wizard

In an interview with The Sun, Waugh told of growing up as an imaginative, nature-loving child and his descent into the Hell of commercial art.

“As a small child I was said to be highly imaginative. I dreamed dreams and saw visions—real ones—and I am doing so still. I remember once when I lived in Delancey place in Philadelphia, and was 3 or 4 years old, of waking up one peaceful morning. I can see the scene almost vividly now at the age of fifty-five. As I awoke I was thrilled with pleasure, for there below me upon the Chinese matting, in the fragrant cool of a fresh morning, by the dim light coming in through the venetian blinds, I distinctly saw and heard a train of cars with an engine come out from under the bed and puff away in a great curve, and then my mother filled the rest of the vision and daytime had begun. Now this was so real that I can hardly believe it was only my imagination.

I was always fond of outdoor, and had an ideal boys’ life there in West Philadelphia before the country which was close at hand was transformed into a modern suburb and all my old landmarks were ruthlessly swept away. There as a boy and a young man, before I thought of being an artist, I had a longing for natural history and science, and was always inventing something, which fortunately fell through because I never had a taste for mathematics or any precise study. I was always for change of scene and freedom and something new and strange and exciting: and yet I have never had anything worse than a gunpowder explosion and blood poisoning to boast of. I tried to be a mechanical engineer before I thought of art. I had been surrounded by painting all my life, my father being an artist, and portraiture became irksome and was exceedingly dry.

“It is both the big and little things in nature which have appealed to me always and in an imaginative way, but I passed through a short period when I was prone to be absolutely visually realistic, and through force of certain environment was persuaded away from the greatness of art to the littleness of only copying nature. It was after this unformed period that I went abroad, married, and was working for the Graphic in London. I had spent a year in the employment of the Harmsworth Brothers before there was a Lord Northcliffe, only plain Mr. Alfred. I painted some miniatures for that family and a portrait and wrought a silver casket for Mr. Alfred. I stuck photographs to magazine pages and drew atrocious ornaments round them to make a pretty page and sometimes they would get me to do them a magazine cover, and these covers were in the decorative line which I was then always trying to exploit in London, but with only a little success and mostly the thanks of the publishers for a sight of them.

Magical Folk and Munes Illustration from The Clan of the Munes

“I did get succeed in getting one little fairy tale written and illustrated by myself into the last throes of a dying magazine. I think it died—oh, well, that’s a stale old joke. I cannot even remember the name of it [The English Illustrated Magazine], but I have the original pen drawings, called the ‘Whikkies.’ The story was called ‘Mable and the Whikkies.’ Later I broke away and illustrated the South African war for the Graphic. ‘With the flag to Pretoria’ and ‘the Gorilla War’ and others, and was counted on the Graphic staff, with a red star against my name on their lists. This lasted all through that war, and on into the Japanese war with Russia, and I illustrated many a bloody deed graphically and academically. My real imaginative work was laid on the shelf—except for some isolated pictures which appeared now and then and which were exhibited in the Royal Academy and all over England and I found I was getting recognition slowly.

“Then when Mr. Thomas of the Graphic told me that his clients were clamoring for photographs of events and he was not giving out much drawing the great break for liberty or death came, and I plunged head over ears into the sea and painted a picture exhibited in the Royal Academy called ‘Mid Atlantic, the Roaring Forties.’ I have been swimming ever since. I don’t’ see how a man of ideas, and creative ones at that, clings to one stunt can be satisfied by giving virility to an ocean wave only. My nature clamors for a wider range than this, and I am the sort who stops at nothing within my liking. I will not do what I do not like in art. I learned this lesson so many times that it is rubbed into me. One cannot do well what one does not like. I firmly believe in art for art’s sake; it is a great achievement to be a real artist and not half a one or a mere copyist of nature. A real artist always creates.

“All through the earlier years I spent in London I wrote fairy tales, numbers of them, and after they had all come back to me again I took a notion to burn them up, which I have kicked myself for since, knowing some of them had stuff in them. However, I still retain the idea, and having gained power to express them, a thing I always believed I should one day achieve, I do not feel that they are entirely lost.

Magical Folk and Munes The Wizard tries to understand the language of the Driftwood Munes.

“The Munes started two summers ago in Monhegan [Maine], where I spent several months both painting the sea and gathering the various pieces of spruce tree parts and making the first drawings. I began by seeing little people with queer tall caps, and then I made careful drawings of roots and placed these little people near them, and by and by I began to think it would be a good plan to form a story, or a series of stories, about these drawings. I had made about ten of them before I left Monhegan.

Magical Folk and Munes, A Mune or American Fairy made of driftwood

“When I came back from Monhegan with those drawings and some large boxes of Mune parts of the following winter I made the pieces of wood into figures in my Montclair studio and then made more drawings of them. All this time I’d been despairing of ever being able to write appropriate stuff to go with the drawings until one evening the whole thing dawned upon me and I wrote the first draft of the story, which I afterward corrected and slightly changed. I am going to model in clay some of the characters in the story and use them in sculpture form, for I have always been a sculptor by nature, it being easier to me than painting or drawing; and I studied modeling under Thomas Eakins in the Pennsylvania Academy.

“To sum up all, I now find myself a successful sea painter in possession of a new vocation, which is really older than the marine painting, being the thing I was born with. What it will lead to be continued in our next.” [sic]

The Sun [New York NY] 4 November 1916: p. 9

Magical Folk and Munes More orc-like Munes https://www.alephbet.com/pages/books/37326/frederick-j-waugh/clan-of-munes

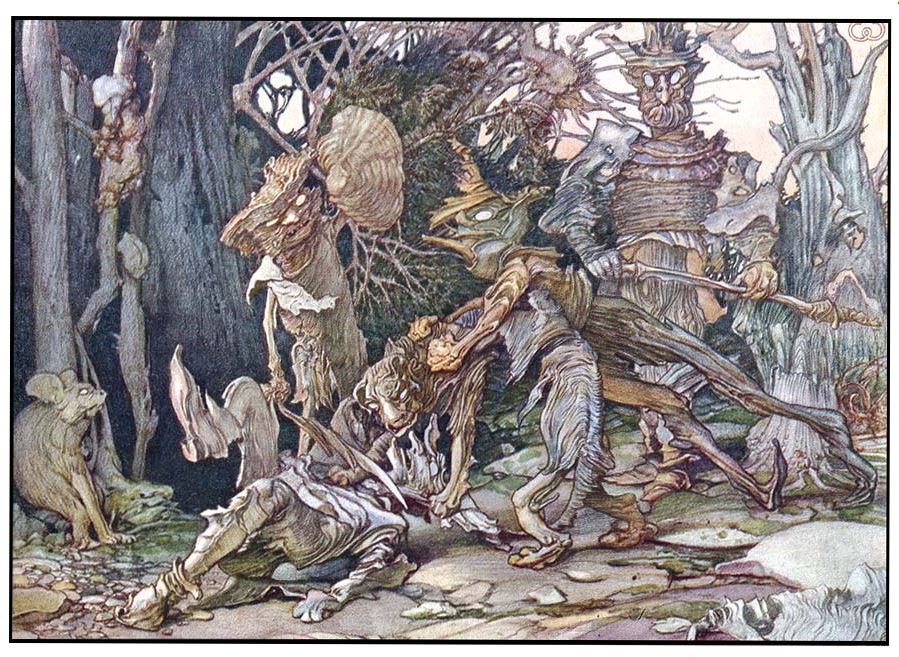

The first article above describes The Clan of the Munes as “amusing.” It was widely advertised as a book for children. I have not read it, but if Waugh’s fairy story “Mabel and the Whikkies” is anything to go by, “disjoint” and “surreal,” might be better adjectives. Recently I have read several eye-witness accounts of walking tree creatures, not unlike the ones depicted above. They, too, were described as fairies; I found them as deeply unsettling as I find the Munes.

Waugh’s Munes have been favorably compared to the goblins of Arthur Rackham. Personally, I’d suggest an affinity with the baroque obsessiveness of some Outsider Art. There is a certainly a Native American influence, but also a grotesque, hallucinatory paganism. They are Wicker Men, Green Men, spiky and malign poppets—disquieting creatures from the landscape of folk horror. These are no friendly guardians of the forest, but the terrible, vengeful fairies of the past, such as are found in Magical Folk.

Earlier in the Sun article, Waugh says: “I am more and more drawn toward this wonderful magnet, this freedom from tradition, this use of one’s own power. Call it imagination if you will, but I call it the portrayal of essential facts, nothing more or less.” That, coupled with his remark about “I began by seeing little people with queer tall caps,” suggests something a trifle more ambiguous than driftwood. Did he “see” them merely with an artist’s inner eye? Or did he believe he was actually portraying “essential facts” he had observed in the woods of Maine?

Thoughts or more on the inner life of the artist? And why “Munes?” All I can imagine is a contraction of the Hawaiian Menehune, but apparently there are also creatures in the book called “Immunes.” chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

And please do check out Magical Folk!

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.

Chris S. sends in this plausible explanation for the name. Thanks, Chris!

“Mune” is “moon”

See: The Scottish Fairy Book by Elizabeth Wilson Grierson (below link) and this online dictionary of the Scots language. I confirmed the Scots dialect with my Scottish friend on Facebook.

So these Good Folk are associated with the moon. From there, many connotations arise with the feminine aspects, dionysian thought, the old matriarchal religions, ad nauseam.