A Man of Vision: the Glass Coffin Inventor

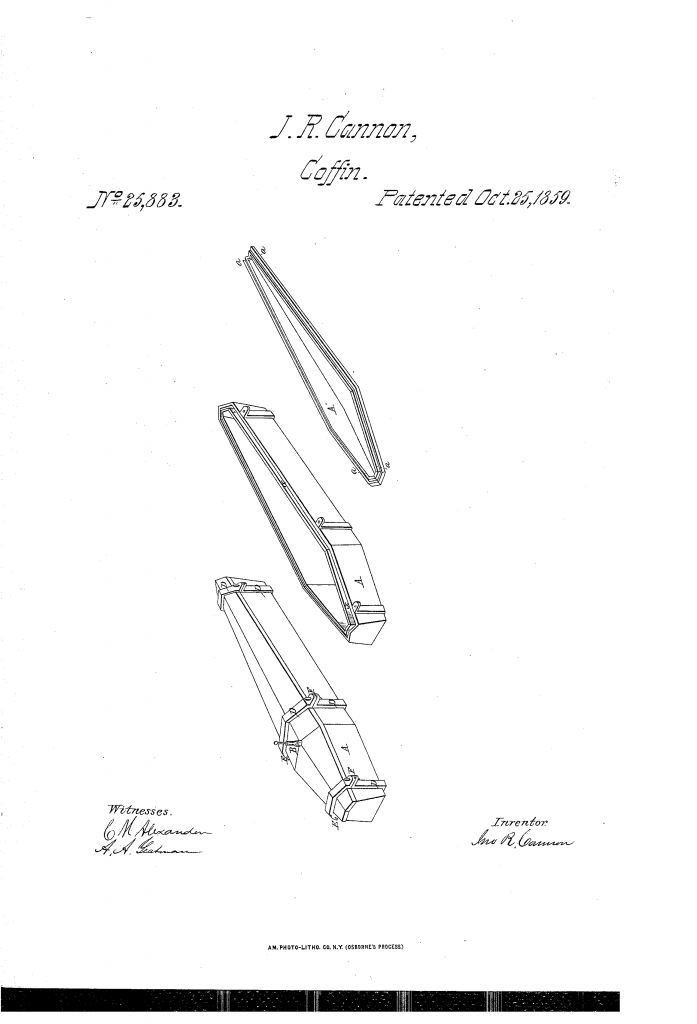

A Man of Vision: the Glass Coffin Inventor A patent sketch for a glass coffin.

A recent article in the Guardian about what happens when urban cemeteries are full mentioned that in Kuala Lumpur and some other Asian cities, the urns of the dead are kept in mechanical columbaria. Specific individuals may be accessed at the touch of a button from the filing system. This reminded me of a piece from The Victorian Book of the Dead, about an inventor of glass coffins, a Man of Vision, creating not just glass coffins, but a vaccuum seal to preserve the body, the design of the vaults to hold them, and a filing system for corpses. He even suggests a pleasant way to spend time with the dead.

COFFINS MADE OF GLASS

“It’s almost worthwhile dying to be buried in one of them,” said the inventor of a glass coffin yesterday to a Times reporter. Henry H. Barry, the speaker, who lives on Fifth street, just below Spruce has for many years interested himself in transparent systems of burial. After conceiving the glass casket he kept it a secret for a long while, until, on October 24th of last year, it was patented. He is searching for a capitalist and the reporter became one for the time being.

“Yes,” continued the inventor, “I believe the success of this thing is going to be immense. There is one San Francisco firm that will take thousands of the coffins to sell to Chinamen.” [to ship bodies back to China for burial.] “What is the advantage of glass for domiciles of the dead?” “In the first place, one has perfect preservation. Before being placed in the vial the patient is embalmed. I may say that the coffin is devised on the walnut shell principle, in two halves. After my customers are once securely packed in coffins I apply an exhaust pump, take out all the air and hermetically seal up the aperture. Then the thing is accomplished. I believe, sincerely, that the whole business will last through several generations. There is the advantage that no infectious disease can come through the glass. The flesh of the subject will preserve its natural tints and relatives and friends will be able to view the deceased for years to come.

“As a sanitary reform it is unparalleled,” he went on; “tenanted coffins can be piled up like any other merchandise anywhere and stay there for years. Some people might prefer to keep relatives in their own houses, nicely put away in the coffins. There is nothing objectionable about the idea. When buried in cemeteries there will be no exhalations whatever, and in case of the removal of graveyards, the coffins can be taken up and carted away with no more offense than would be given by so many kegs of nails.” “What are [sic] the dimension and shape of the coffin?” asked the reporter.

“They can be made of all sizes. The glass is three-eighths of an inch thick, and the coffin is oval with a concave top. It would not do to have it flat as with a vacuum inside it the glass would collapse.” “Wouldn’t they get smashed in cemeteries?” queried the incipient investor.

“On the contrary. We have a system of toughening the glass that makes it like iron. A spade struck against the coffin with a good deal of force will not break it. Body-snatchers would get their fingers cut, but that’s all right. I don’t legislate for ghouls. There is no end to the variations which can be made on these coffins. The glass can be clouded so that only the face is visible. It can be colored, or butterflies and weeping willows can be placed at intervals all over the surface. There are a thousand ways of ornamenting the exterior.”

“What will they cost?” was the next question.

“From seven up. Seven dollars, I mean, of course. They could possibly be manufactured of such choice material and so beautifully etched as to cost as much as a thousand dollars each. I have often wished that at the time of President Garfield’s death I had had a glass coffin. I am sure it would have been used. I propose to form a company, with a capital of some half a million of dollars. No, sir, I will not sell you the patent outright, so it’s no use pressing me to do so. I have too much faith in its future for that. Another reason is that I am determined it shall not get into the hands of monopolists who will run up the price of coffins to a fancy figure. This casket was invented as much with the idea of benefitting the poor as anything else. Of course there will be money in it for me, and I suppose I shall have to accept whatever comes.”

Mr. Barry then proceeded to unfold the particulars of a remarkable scheme. He said that he had often heard a proposition discussed for excavating and constructing huge catacombs in this city for the reception of the dead. In that case, he thought, his invention would be invaluable. He called the scheme a “trust and safe deposit idea.”

“We should have a vast system of vaults,” he explained, “in which coffins would be placed. Spaces could be reserved for families. Here, in a stall, would be a father; by his side his wife; on the upper shelf the grandmother and grandfather, and above that the other ancestors. Each coffin would have a number at its foot, and catalogues would be issued giving the names of the occupants, for instance, ‘Henry Jones, 241.’ Above the vaults would be a suit of elegant reception rooms into which visitors would be invited. They could sit down and call for, say, ‘No. 241.’ An attendant would go down stairs, slide the casket indicated up on to a little barrow, come back again and leave it with them as long as they liked. They could look at it, have it taken to its shelf when they were through, and return home. A certain amount of rent would, of course, have to be exacted. What do you say of going into the enterprise? It will ‘take’ assuredly. There are a lot of other millionaires thinking the matter over, so you had better decide at once. Good afternoon. Let me hear from you in a few days.” Philadelphia Times

Jersey Journal [Jersey City, NJ] 29 March 1883: p. 2

Of course glass coffins weren’t really new–Alexander the Great was said to be buried in one and there were reports of ancient Egyptian coffins made of glass, but perhaps the vitrified faience inlays were what was being described. Glass coffins were the resting places of many sacred corpses or parts thereof, of spouses kept above ground for inheritance purposes, and of fairy-tale princesses. It’s the up-to-date sales-pitch with all the add-ons that sets this maker and his inventions apart. You might say Barry was thinking outside the box.

Another article gives Barry’s glass coffin patent date as 24 October 1882, but I haven’t been able to locate it. I’m also really quite perturbed that I cannot find an image of a glass coffin I thought I’d saved–it was a lovely purple-ish color and molded with dragonflies, like a piece made by Lalique. I also had an image of a row of glass coffins from an Indiana glass coffin factory. Search for “glass coffins” and pretty much all you find are the waxen cadavers of dictators and saints.

Other early filing systems for human remains? Chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Thanks to Michael Robinson for sending me the Guardian article.

Most of the post above appears in The Victorian Book of the Dead, also available in a Kindle edition.

See this link for an introduction to this collection about the popular culture of Victorian mourning, featuring primary-source materials about corpses, crypts, crape, and much more.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.