Morfa Resonance: The Pit of Ghosts

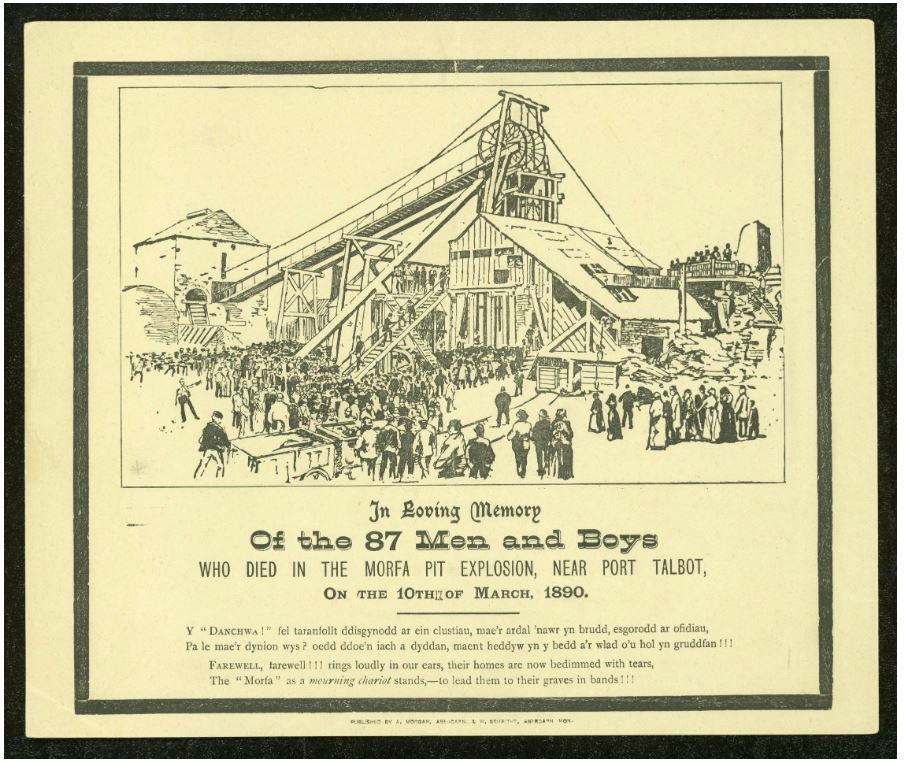

Recently Dr Beachcombing wrote about the many premonitions of disaster occurring before the Morfa Colliery explosion of 10 March, 1890. The colliery, which was known as a “gassy” mine, had a long and deadly history. There were explosions in 1858 (4 men killed), 1863 (30 or 40 men killed), and in 1870 (30 men killed), when the mine had to be flooded to put out the resulting fires. What I propose to look at today is the sequel to the 1890 disaster or, perhaps, to the entire grim history of the Morfa pit, which became known as “the pit of ghosts.”

Reports from the days and months after the 1890 disaster almost invariably mention superstition in connection with the warnings told of in Dr Beachcombing’s post.

“Other curious instances of warnings are freely spoken of which would yield matter of interest to the student of either folk or spirit-lore.’’ Such stories used to be quite common in the mining districts of Wales in connection with every disaster of this kind, and although the spread of popular education has done much to deaden the popular fancy and to kill off the old superstitions, it is quite clear that the land of the corpse-candle, the phantom funeral, the coal-finding gnome, the sprite and elf and fairy, is not yet denuded of all its poetical traditions.—Christian Herald, March 19th. Quoted in The Two Worlds: A Journal Devoted to Spiritualism, Occult Science, Ethics, Religion and Reform, 28 March 1890: p. 229

Some men even went on record with their belief in omens:

There is an abiding belief among the men of the Morfa Colliery that signs of warning preceded the terrible accident by which eighty-seven lives were lately lost. Not only is this floating belief current among the gossips, but it is sufficiently firmly held to be testified to on oath. In the course of the inquiry into the cause of the disaster the following evidence was given on oath:—

Peter Williams, questioned why a special examination of the pit was asked for previously to the day of the explosion, said (speaking in Welsh): The truth was there had been complaints of spirits being about in the four-foot vein. He supposed the colliers thought a special examination would get rid of the spirits. Another witness, named Harding, said a rumour had gone round that something was to be heard in the pit, and it was regarded as a proof that something unusual was to occur at Morfa—a fire or an explosion. He himself thought something would happen in the four-foot. The sounds they heard created fear in the minds of the men that there was danger in the pit. About a fortnight before the explosion he was in the four-foot with another man. After emptying a tram they went on their knees. No word passed between them; but they heard something, and looked at each other in amazement. One asked, “What is that?” and thereupon a door opened and slammed against the frame. He met Tom Barrass, the undermanager, and said to him,” Something very strange has happened there to-day.” Barrass remarked, “Well, I can’t doubt that this sort of thing makes one believe that everything one has heard before is true.” There were some people who were superstitious, and he had his ideas before the explosion; but he had come to believe that it was something else that caused the accident. He had proof himself that sounds and signs occurred before the explosion of 1883. Light, Volume 10, 3 May 1890

The tokens of the disaster as reported several months after the explosion were weird and varied:

PITMEN’S SUPERSTITIONS.

As the excitement connected with the awful colliery accidents in South Wales has died away, it may not be out of place to give a few interesting facts, as personally related to the writer, concerning the hallucinations which many of the colliers who worked in the Morfa pit laboured under before the disaster.

Mr Isaac Hopkins is the manager of the well-known Dynevor Collieries, at Neatb, and he told Mr George Palmer, of Neath, that a great many men had come to him from the Morfa pit seeking work, giving as their reason for leaving that “the Morfa pit was certainly haunted, and that some terrible calamity was about to occur. Several of the men declared that “there were frequent peculiar noises as of ghostly trams running wild in the pit, with heavy fails of coal and debris which never happened; that at times strong and most remarkable perfume spread itself all over the mine, the odour being like that from clusters of roses, clematis, and honeysuckle. Nothing could be seen, but scent of the most exquisite kind was honestly stated to have been frequently inhaled.” Others of the men stated that “a huge red dog was daily seen prowling about the workings, that it suddenly disappeared, and it could be none other than a ghostly dog and a sure omen of great evil; also that a strange man, dressed in oil-skins and wearing a leather cap tightly fastened over his ears [shades of Spring-heel Jack?], one day suddenly appeared on the cage of the pit, and, after waving his hands upwards as if in despair, faded away into thin air.”

An old collier named Thomas swore that he saw a weird-looking man jump on a journey of trams underground, and after riding some distance jumped off and melted away in the darkness of the mine. This statement was confirmed by a man named Beece, who both declared they recognised him as a pitman who died years ago. These, with many other tales of the most extraordinary kind, the mining population about Taibach even now pin their entire faith in. Press, [Canterbury, NZ] 22 December 1890: p. 6

But the noises and presences did not end in 1890. It was said in the papers that only six bodies were not recovered from the 1890 disaster; a list found here suggests that 44 of the 87 dead were not recovered–ample reason, from a classic ghost-lore perspective, for the echoes of the dead to linger and for the mine to be haunted.

In 1895 the mine was hit with a wave of new terrors.

WELSH MINERS SCARED They Leave Work in a Panic Owing to Uncanny Noises

London, Dec. 20.

The latest sensation for lovers of uncanny things is a haunted coal mine. It is situated at the Morfa colliery in South Wales. The spooks first made their presence manifest last week by indulging in wailing and knocking all over the underground workings. There could be no doubt about it, as several hundred miners heard mysterious sounds which were unlike anything they had heard before. They were so thoroughly scared that they threw down their tools and went to the surface and refused to resume work until the ghosts had been laid.

It has been suggested that the trouble at the Morfa colliery is due to the “coblyns” or fairies supposed in Wales to dwell in mines. But the miners themselves scout the idea. Coblyns, they say, are friends of the miners, and when they knock or shout or throw bits of coal about, it is for the purpose of letting the men know where the best veins of coal are to be found. The suggestion that the mysterious and terrifying wailing came from a tomcat, which had strayed from the mine stables and got lost in the workings is unanimously repudiated and denounced as unworthy trifling with a solemn subject. The Ottawa [Ontario, Canada] Journal 21 December 1895: p. 3

No longer were strange noises signs of disaster: the mine was declared haunted by the victims of the 1890 explosion.

SPOOKS IN WELSH MINES

Workmen Frightened Away by Mysterious Noises

The latest sensation for jaded lovers of uncanny things is a haunted coal mine. It is situated at the Morfa colliery, in South Wales. The spooks first made their presence manifest by indulging in wailing and knocking all over the underground workings. There could be no doubt about it, as several hundred miners heard mysterious sounds which were unlike anything they had ever heard before. They were so thoroughly scared that they threw down their tools and went to the surface and refused to resume work until the ghosts had been laid.

Recent efforts to persuade the men that the mine was perfectly safe and spook proof, and that the noises were due to natural causes, succeeded, and the men reluctantly returned to their work. Some had begun to be somewhat ashamed of themselves and made pretense that they had feared not ghosts, but some physical disaster, of which the noises were intended as a warning. But the majority fervently persist in the belief that there is a supernatural explanation and incline to think that the trouble is due to the disturbed spirits of six workmen who were killed in an explosion which occurred six years ago, and whose bodies were never recovered. Some of the men have declined to go down again until those bodies have been found and decently interred with Christian rites.

The evidence in favor of the supernatural theory is still considered abundant and plain enough for the average Welsh miner. Scores of men heard blood curdling noises, and several saw doors and brattices moving in the most unearthly manner. People abroad after dark are said to have heard the singing of dirges and the roll of muffled drums. Repository [Canton, OH] 5 January 1896: p. 6

Reported even longer after the fact, was this tale of the omen of the “Seven Whistlers,” which was not mentioned in any of the 1890 accounts I have found. These creatures seem to be the ornithological wing of the Wild Hunt.

WARN OF DANGER

SEVEN WHISTLERS UNCANNY

Peculiar Noises Like Yelping Supposedly Heard in Parts of England Before a Disaster.

In some parts of England peculiar whistling or yelping noises are heard in the air after dusk and early in the morning before daylight during the winter months. Sometimes, however, the noise is described as beautiful sounds like music, high up in the air, which gradually die away. The general belief is that the “seven whistlers,” as they are called, are the foretellers of bad luck, disaster, or death to some one in the locality.

It is a very ancient suggestion. Both swifts and plovers have been suggested as the “whistlers.” It may be noted that plovers are traditionally supposed to contain the souls of those who assisted at the crucifixion and in consequence were doomed to float in the air forever.

Like Singing of Larks.

In Shropshire the sound is described as resembling that of many larks singing, and the folklore of both Shropshire and Worcestershire says, “They are seven birds, and the six fly about continually together looking for the seventh, and when they find him the world will come to an end.”

Everywhere, without exception, the “seven whistlers” are believed to presage ill, but the superstition seems to be more particularly a miners; notion. If they heard the warning voice of the “seven whistlers,” birds sent, as they say, by Providence to warn them of an impending danger, not a man will descend into the pit until the following day.

Heard Before Explosion.

Morfa colliery, in South Wales, is notorious for its uncanny traditions. The “seven whistlers” were heard there before a great explosion in the sixties and before another, in 1890, when nearly a hundred miners were entombed.

In December, 1895, it was said that they had been heard yet again, whereupon the men struck work and could not be induced to resume it until the government inspector had made a close examination of the workings and reported all safe. Muskegon [MI] Chronicle 17 June 1904: p. 6

Another article on the “Seven Whisperers” says that the Morfa mine was a “singularly unlucky pit,” and that

In December, 1896, the scare broke out afresh, as a repetition of the same curious noises [as in 1890] took place, and, direst portend of all, one Sunday night a dove [one of the three “corpse birds:” robin, pigeon, and dove] was found perched on a coal truck in the weigh-house. By way of reassuring the miners, who had struck work in a body, the Government inspector, the chief manager, and a small party of officials made a strict examination of the workings, but although they found nothing changed it was several days before the superstitious miners could be induced to resume work. Auckland [NZ] Star 17 January 1903: p. 5

The miners read the jocular pieces ridiculing their “superstitions” and rightly resented the slur.

A reporter from the Western Mail wrote: “I visited Morfa in quest of a ghost. In arriving at the place I found the Morfa miners standing in groups at the street corners. Being descendants of the ancient Silurians, these men are very brave, and, like their ancestors, they would meet a charge of cavalry on foot. But, if they are equal to all kinds of flesh and bones in war or peace, they are terribly afraid of ghosts….

It is all very well for the reader seated in the daylight at his fireside, to call the Morfa miners “superstitious,” because they on hearing strange and unexplainable noises in the dark caverns of the earth…One of the miners today, standing among his fellows, with his hands in his pockets, a pipe in his mouth, told me he had read the editorial comments in the Western Mail that morning on what they were pleased to call the “superstition” of the Morfa miners. “Tell the editor,” he said severely, “to confine his remarks to things of this world, for he knows nothing about heaven and hell and the workings underground.” And he added the remark that if the Western Mail editor had been seated in the dim light of a clammy lamp in the interior of the workings, and had heard groaning in the darkness beyond and below in the deep, he, too, would have taken to his heels and quickly sought “some hole to hide in.” Another miner, sharp-eyed and seemingly highly intelligent, declared to me that there was not the slightest doubt that inexplicable strange noises had been heard in the workings both lately and before the explosion six years ago. This belief, which he declared 50 percent of the men believed, has been intensified by the finding the dove at 10 o’clock on Sunday night close to the mouth of the shaft…. The Scranton [PA] Tribune 28 December 1895: p. 6

Considering the noises and alarums the miners experienced in 1895-1896, they must have been relieved that there was only one fatality in 1896—a man who died of dropsy exacerbated by a fall in the pit. As far as I can find, the Morfa Colliery had only isolated fatalities—no large-scale disasters–from 1890 until it closed in 1913. Is the pit still believed haunted by the men who died there? And what toxic gases found down a coal mine might produce a sweet, flowery scent? chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Various materials have been believed over the centuries to trap spirits: iron, crystal, and various gemstones. Coal is not one of them, yet the mines and their communities teem with mysterious voices, knocking kobolds, silently flitting Women in Black —and the spirits of those men and boys buried, not beneath decent slate in the churchyard, but under tons of rock and smouldering slag.

At these links you’ll find posts on a haunted mine, a black spectre in a mine, a headless miner’s ghost, and a subterranean centaur scaring miners off the job.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.