Mothered by a Ghost: Patience Worth’s Daughter

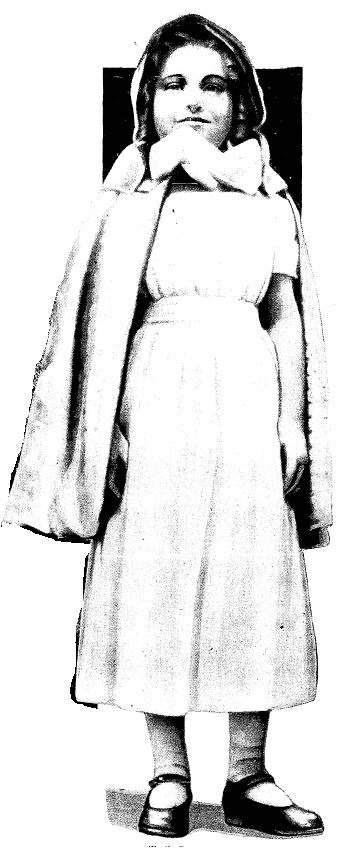

Young Patience Worth Curran in the “Puritan” clothes selected by her “spirit mother.”

Tomorrow is Mother’s Day and as I am nothing if not topical, today we look at a strange case of spiritual motherhood: the mother-daughter duo (or perhaps trio) of Pearl Curran, her adopted daughter Patience, and the “ghostly mother,” Patience Worth.

One of the odder incidents in the Curran/Worth saga was that of the adoption of little Patience Worth Curran also known, nauseatingly as “Patience Wee.” Mrs. Curran, married to a man 12 years older, was childless. The article below describes how “Patience Worth” told her to adopt a baby, specifying the child’s blood-line, sex, and color of eyes. When a suitable pregnant, and conveniently dying, woman was found, Mrs. Curran quickly snapped up the rights to her unborn child. Patience predicted the time of the infant’s arrival and, during its childhood, gave child-rearing advice. As the illustration shows, the little girl was sometimes dressed in the early 20th-century version of “Puritan” clothing at Patience’s behest.

The clothing may be a clue to the origins of the Patience Worth story. During the 1910s, there was a Colonial revival in architecture, household furnishings, and clothing. It also led to a spate of Olde World Tea Shoppe/Bide-a-Wee Inn language in advertising and literature. I have not previously seen this suggested in connection with PW and wonder if this trend influenced the Curran ouija sessions.

This obituary lays out the essentials of Pearl Curran’s life and the adoption of baby Patience.

Death Silences the “Spirit Voice” of Patience Worth

For 25 Years This “Disembodied Intelligence” Which Said It Died Three Centuries Ago, Dictated Novels, Adopted a Baby and Bossed a Living Family, but Now Has “Died” a Second Time.

“Soon will my voice be mute.” It was the mysterious “entity” Patience Worth claiming to be the spirit of a woman who died in Shakespeare’s time and, as usual, she was talking through the Ouija board, in the hands of Mrs. Pearl Curran, at Santa Monica, California.

After that prophecy, the second she is ever said to have uttered in nearly a quarter century of messages form the world of the dead, the voice stopped. Mrs. Curran’s family wondered if it would speak again or if this prediction, evidently indicating Mrs. Curran’s death, would be fulfilled as was the other which dealt with birth. This was last November and a cold Mrs. Curran had caught soon developed into pneumonia, bringing death on December 4 [1937]. With her died the voice of Patience Worth.

The family held what was really a funeral ceremony for two persons, Mrs. Curran, fifty-six [54] years old, and Patience, the curious intelligence which believed it was the spirit of an English Puritan girl which found its way back to earth in order to “complete the experiences of an unfinished life.”

That some sort of separate consciousness was hovering about, either in or outside of Mrs. Curran, and expressing itself through her, is hardly to be doubted. Spiritualists believe that Patience Worth was exactly what she said she was, a spirit from another world. The late Dr. Morton Prince, eminent physician, psychologist and professor of nervous diseases at Tufts College, and some others who investigated the phenomenon were inclined to think it a case of dissociated personality, but there was never any question of fraud.

The speed with which the words rushed through precluded the possibility of trickery. Mrs. Curran, wife of John H. Curran, former State Immigration Commissioner at St. Louis, Missouri, was a fairly busy housewife in her early thirties who read little, had no literary ambitions and about as much knowledge of the Shakespearean era as of the Fiji Islands.Such a person might, after many years of study, learn the vocabulary and peculiar phraseology of that period and possibly write a novel in that style good enough to get published, but such a work would be hammered out slowly and painfully. It is doubtful if Mrs. Curran under normal circumstance, could have produced even one poem in a lifetime of any merit.

From the very beginning Patience Worth’s dictation has come through Mrs. Curran so fast that the problem has always been to keep up with her in writing it down. In 1913 the Ouija board happened to be enjoying a momentary fad in Detroit and one evening the Curran household with friends were playing with the toy when Mrs. Curran suddenly cried out:

“I have a message coming. Take it.”

Mrs. Curran looked away from the board but her husband watched the pointer as it flew from letter to letter, spelling out the following:“Many moons ago I lived.

“Again I live, Patience Worthy my name.

“If thou shalt live, then so shall I.

“I make my bread by thy hearth.”

Thus the invisible stranger introduced herself and announced that she had moved into the family circle. She told in archaic English of her life as a Puritan maiden who worked so hard spinning flax that her thumb had become enlarged and she had died without experiencing the joys and sufferings of motherhood. Neither had Mrs. Curran, at that time, though it was not considered significant at the moment.

Though Patience ate no food and took up no space in the household, she certainly did consume a lot of its time and for this she set out to repay them by dictating a series of novels, parables, poems, and miscellaneous writings.

There was just one notable exception to her headlong speed of dictation. Patience had stated that at the next evening session she would begin her most important work, a historical novel dealing with the life of Christ. As the family gathered expectantly about Mrs. Curran and she placed her hands on the board, for the first and only time Patience faltered.

“Loth, loth I be,” the pointer spelled out. “Yea, thy handmaid’s hands do tremble. Wait thou! Wait! Yet do I to set” (to write). For a moment the pointer aimlessly circled the board until finally it picked out the sentence: “Loth, loth I be that I do for to set the grind” (the circling motion of the pointer.). Then the ghostly authoress asked for a period of quiet.

“Wait ye stilled,” she commanded. “Ah, thy handmaid’s hands do tremble.”

There were several minutes of silence in the room, then the pointer flew into action with Heia’s cry in the night:

“Panda! Panda! Tellest thou the truth?”

The novel, entitled “The Sorry Tale,” had begun and never was there another instant of hesitation to the end of its 640 pages. In one evening the chapter of the crucifixion came through with over 5,000 words. It is difficult to believe that a non-literary woman such as Mrs. Curran alone could have poured forth such quantities of words without once making a slip in her archaic language.Even more remarkable than the prose, because of much higher quality , are Patience’s poems. For example, the very last one to come through before the prophecy that the voice would soon be mute is the following which was read at Mrs. Curran’s funeral:

MIRE SONG

“To sing of mire?

The silt mayhap of stars.

The ash of aged Mays

The bones of Kings who mouldered in

Their pride in other days.

Black-petaled roses, old as age, have writ this page.

“Mire? Who may gainsay I am the stuff from which the Spring is born?

The stuff that spurts bedecking her fair morn in verdure and in bloom,

From which the sweet perfume exudes,

And stifling, bears a dream.

A dream of pageantries that passed,

Of pageantries that could not last,

But passing scribe my substance with immortality!

“Priest, sinner, lout, the beggar in his clout,

The mighty hands that make a might thrust,

The shining blade, its blood-bit rust—

One by one become but dust

And thus with me a part of common sod,

Awaiting the hand of God.

Mire? The common heritage of birth.

Mire! From which God called to being, Earth!”

The Mire Song is part of “A Shakespearean Fantasy” for which Patience Worth had been sending through material, from time to time, during the last two years of Mrs. Curran’s life. This material is now being surveyed by Mrs. George Peters, the former Patience Worth Curran whom Mrs. Curran adopted before the child’s birth, at the command of Patience Worth.

That was after the second book had been published and though the Currans never made any fortune out of the “ghost-writings,” the returns were not negligible. One day they were all discussing how the money would be spent and Mrs. Curran asked her spirit mentor if she had any ideas.

In her quaint English Patience reminded them that she was a Puritan girl who had not come back to earth and done all this dictating without a serious purpose and she was earning the funds to accomplish that purpose. Patience wanted to experience the joys, sorrows and worries of motherhood through Mrs. Curran, but since that lady was childless this would have to be done by adoption. This was shock enough but Patience laid down conditions which made it hard indeed. The child must be a girl, with certain color of eyes and other physical specifications and, as in her own case, one parent must be English, the other Scotch.

The Curran family, including as it did Mrs. Curran’s two parents, was large enough, but they decided to look around and see what would turn up.

Nothing did but obstacles, one orphanage refusing to have anything to do with a family that played with ghosts.

One day Mrs. Curran heard of a woman who had just become a widow and was in such poor health that she would probably die in her expected childbirth. Patience assured them that this was the right baby at last and ordered them to make the adoption arrangements in advance of birth while the mother was still alive to sign them. It was done though Mrs. Curran put in a proviso, calling the adoption off in case it happened to be a boy.

But it was a girl with just the proper specifications.

The natural mother died a few days later, and for several weeks little Patience’s hold on life was feeble. During this period its ghostly mother gave medical advice, such as firing the first doctor and recommending “herbing the child with fennel water.” From this it was assumed that little Patience was to be a child reared by a ghost. But once her health was secure, the spirit voice only gave kindly advice, such as suggesting the child wear quaint Puritan clothing. In an interview the other day, Mrs. Peters said:

“We came to think of Patience, the spirit, as a wise, thoughtful and considerate member of the family but never did she interfere in my personal affairs. My diet, habits and companions were much like those of any other girl. When mother used to reprimand me as a little girl, I sometimes told her, “Ask Patience if I am wrong.’ But these appeals never won me anything.

“Mother never felt that she was the reincarnation of Patience nor that I was. Patience to her and to all of us was a distinct separate personality. Her interest was in Mother, not in me.

“We always felt she was within our call and reach when Mother was here. Now she is gone just as certainly as Mother is gone.

“After we came to California I fell in love. That was all of my own accord, just as any girl does and completely without any conscious suggestion from Patience. I did not consult her about my plans to be married. So I married George Peters, but I was quite young and we couldn’t’ make a go of it. About a year ago we separated.”

If Patience wasn’t a ghost, what was she? She may have been that vaguely understood thing, a dissociated personality. One form is amnesia in which a person may lose all recollection of his previous life, even his name. If the first personality returns he loses all memory of the second one. In another form the secondary personality never gets a chance to reveal itself except by talking during sleep or by automatic writing in which the secondary manages to write messages when the primary is not paying attention. Ouija board communications seem to be a form of automatic writing.Though most poems are laboriously wrought out, occasionally a poet suddenly finds one all complete in his mind, with nothing to do but write it down. It is now believed that these inspirations are not sudden but that the subconscious mind has put in long hours of work, perhaps during sleep, only tossing the poem into the conscious mind when it was perfected. Patience Worth may have been a secondary personality doing that for Mrs. Curran, the primary personality. This does not explain Patience’s two predictions, but, on the other hand, she was not omniscient. Evidently she did not know that sometime after the adoption Mrs. Curran was destined to have a natural daughter, Eileen, which would make the adoption needless.

Plain Dealer [Cleveland, OH] 30 January 1938: p. 63

I have always been a little impatient at the mystery surrounding the Pearl Curran/Patience Worth communications. Hailed as a masterpiece, A Sorry Tale strikes me simply as a faux-archaic production where every other sentence begins with “And…” And there is rather too much of “yea!” and “alackaday!” It is of the same mediocre ilk as the channeled blather from Space Brothers or Atlantean warriors. And, well, “Panda”…?

I have often seen it said that Patience used no vocabulary from after the 17th century, but as the only named witness to this is Casper Yost, a promoter of Pearl Curran and her work, I would like to see a modern linguistics expert take a look or even run the poems and stories through analytical software that can detect authorship. Although Mrs. Curran’s life has been studied for clues, I suspect that her gift was simply that of cryptomnesia. It took a surprisingly long time to unmask Virginia Tighe’s neighbor Bridie Murphy Corkell as the source of her “previous life” as Bridey Murphy. I wonder if there wasn’t some long-forgotten influence on young Pearl who moved around a great deal as a child and who was said to have an excellent memory. It was said, for example, that Mrs. Curran knew nothing more about the Holy Land than she learned in Sunday School so how could she draw such a vivid picture of life there in the time of Christ? Magic lantern shows featuring slides of the Holy Land were popular attractions for Sunday Schools and lectures. Engravings of religious scenes and sites of the Holy Land were featured in books, magazines, and newspapers. The Biblical epic, Ben Hur, by Lew Wallace, was published three years before Pearl Curran was born, and was a wildly-popular book and stage presentation in the United States for years after that. It would not have been difficult for a retentive child to internalize Biblical imagery from these kinds of sources. Professor Daniel Shea has also suggested that Pearl “crammed” for her ouija board sessions by reading background material. [SEE: The Patience of Pearl: Spritualism and Authorship in the Writings of Pearl Curran, Daniel B. Shea, University of Missouri]

The subconscious has hidden abilities that may seem supernatural. President Garfield could write Greek with one hand and Latin with the other—simultaneously. Some Spiritualist mediums could write automatically with both hands at once, while rapping out a third message with their feet. Young women with limited educations would rise and preach lengthy sermons while in trance. And, I suspect that these trance and rapped communications—including those of Pearl Curran—were considered to be more profound than they might otherwise have been merely because of their “spiritual” method of production. We have not got the mechanism nailed down, although I think that brain scan studies will eventually find it. But I am not sure we see anything supernatural in the “writings” of Patience Worth.

But let us return to the story of Pearl and her daughter. Often the story ends with Pearl’s death and the (to my mind, merciful) silencing of Patience Worth’s voice. Young Patience’s story had a melancholy end.

Mrs George Peters, the Former Little Patience Worth Curran, as She Is Today.

When Patience was in her teens the family moved to California, where she married George Peters. She, herself, became a mother, but the ghostly Patience, apparently, had no interest in being a grandmother, and paid no attention to the new child.

The marriage was brief. The couple separated in 1937, and a little later went through the divorce mill. In 1940, Patience became Mrs. Behr. [A wealthy fan of Mrs. Curran’s, from New York, Herman Behr, helped to support her after her husband died. Mr. Behr had a son Max, who was a champion golfer and golf course architect. I assume this is the Max Behr whom Patience Worth Curran Phillips married?]

In 1938 [surely a misprint–she died in 1937], as Mrs. Curran was sitting at the ouija board it spelt out a cryptic message:

“We are nearing farewell. It has been well to speak for a time, but silence is eternal, and soon, too soon. My voice again must be mute.”

Mrs. Curran fell gravely ill, and, during the same year died. [She said that she had been warned by Patience that her death was coming, even though she was in good health.]

Since then, Patience Worth, the long-dead Puritan maid, has never communicated by ouija board with her adopted daughter and namesake, nor, so far as is known, with anyone else.

Those who believe in ghosts, however, probably would suspect that Puritan Patience had something to do with a remark made by Mrs. Behr shortly after her 27th birthday last October. Though seemingly in good health, she observed to her husband:

“I have a queer feeling, Max, as though this were going to be my last birthday.”

A little later the young woman who had been “mothered by a ghost” began to lose weight. She complained of sleeplessness, of an oppressive feeling that descended upon her each night.

A doctor’s diagnosis showed a heart ailment, not of a serious nature.

However, she continued to complain of insomnia. And one night a few weeks ago, after taking a sleeping tablet, she died.

The attending physician pronounced death due to natural causes. But to believers in the ghostly Patience Worth, there was another, less rational answer.

The Puritan Patience, they felt, having realized the earthly experiences she sought, no longer had any use for the human beings through whom she had realized them. Oregonian [Portland, OR] 16 January 1944: p. 53

A rather heartless conclusion: Patience Worth had satisfied her thirst for life, literature, and motherhood through surrogates, who were now discarded. She might be said to be a “hungry ghost,” obsessing a living host to re-live a vanished life. I am reminded of the so-called “vampire mother,” beloved of the late 1910s and 1920s popular press: an imperious figure who required that her children give her abject devotion and sacrifice their lives to her service. Pearl Curran, while she undoubtedly felt that her life had been enriched by Patience, died at age 54. There is anecdotal evidence in the Spiritualist literature to suggest that mediumistic activities can cause illness in their practitioners. Did the work of transcribing the demanding spirit, whether a projection of Pearl’s subconscious, a hoax, or a ghost, shorten her life?

Previous Mother’s Days posts: Maternal Influence and Monsters and The Ghost of a Dead Mother Visits her Baby. while Mrs Daffodil tells of another ghostly mother who threatened her successor.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her new blog at The Victorian Book of the Dead.