In a Munich Dead-House

In this, our second in the occasional series, “Little Visits to the Great Morgues of Europe,” we find ourselves in Munich. I will point out that the “waiting mortuaries” of Germany represent a separate class of establishment from the average morgue. The persons in them were generally properly identified and there were separate buildings for suicides and the unknown dead, which were not open to the public.

There were some ten “Leichenhauser,” in 1907 Munich and they were the pride of the city. While they were on the list of must-sees for tourists, descriptions of the German Leichenhauser by visitors seem less fraught with drama than those of the Paris Morgue. In reports describing the Paris morgue, there is an emphasis on the sight and smell of rotting corpses and the disorderly lives of beautiful suicides, whereas the principal impression for visitors to Germany mortuaries was that they reeked of flowers and disinfectants. Our intrepid visitor clucks over children exposed to the sight of corpses, but there are no maggots in the Munich Deadhouse.

IN A MUNICH DEADHOUSE.

By Leon Mead.

The methods of burial in some portions of Germany seem very strange to the average American. In Munich, Bavaria, when a person dies, he or she is taken to the Deadhouse immediately, or at least as soon as the body has been washed and dressed. The origin of this peculiar custom dates back many decades, and in these days is followed partially as a sanitary measure.

Munich is exposed to most of the fatal epidemics which devastate Italy, though in these days the inhabitants do not suffer those fearful and unmentionable plagues that used to decimate the town in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The tenement houses, however, are densely crowded, and extreme poverty generally is apt to be attended with disease. Many large and all but destitute families live in one or two rooms, and when death overtakes a member of such a household there is no suitable accommodation for the body. Moreover, it is a Catholic superstition in Bavaria not to sleep under the same roof with a dead person.

The system is compulsory, taking in the high as well as the low, and the rich as well as the poor. Otherwise, many of the poorest people would insist upon the right to keep their dead in their own houses, however squalid, until the hour of burial, were the rich allowed the privilege.

The arrangements for the interment of the dead in Munich are performed by officials and women, the latter being called Leichen Frauen. The remains are conveyed in a hearse to the cemetery that belongs to the quarter in which the deceased has lived. It is not until one visits the Munich Dead house that the horror of it can be realized. The whole area (the old Southern Cemetery is here referred to) is inclosed with a brick wall several feet high, and the general plan of the cemetery itself, with its artistic arcades and imposing monuments, entitles it to the reputation it has acquired of being one of the finest in all Germany. Intersecting each other in the centre are a driveway running east and west, and abroad, paved walk extending north and south. Parallel to the driveway, on the northern side, stands a long, low brick building, a part of which is occupied by the corps of directors of the cemetery. This building is all but divided by a roofed passageway connecting the northern and southern walks. On the west of the passage is a large room which serves as a temporary repository for suicides, murdered people, and those who are killed by accident. The windows of this room, which is not open to the general public, are curtained with green muslin. On the east side, the first chamber is designed for the bodies of the common people. By ascending a step or two at the entrance one can see through the wide glass door or through the adjacent windows, a spectacle sufficiently ghastly to cause any foreigner to grow faint. It is a repulsive and awful sight.

On each side of the rectangular room is ranged a row of slightly inclined biers, on which rest the cheap yellow-covered coffins containing all that is mortal of from twenty to forty human beings. The faces of the emaciated old women, with their sharp, cronelike chins and sunken eyes, their open. mouths disclosing one or two discolored teeth, are enough to sicken most spectators at a glance. And yet to many there is a grim fascination about it. Indeed the Müncheners regard going to the Deadhouse on holidays as a standard recreation, and always recommend it to visitors with a weird sort of pride. They go through life perfectly unconcerned over the prospect that some day they, too, will be taken there to lie in lowly state for three days before the clods of the grave close over them.

What a grim picture for little children to become accustomed to! The Morgue in Paris is tame beside it. What could be more grewsome to see than the sallow-visaged old men lying there, with the crucifix and, perhaps, a wreath or two of evergreen on their breasts, two caudles at their heads—placed there with the conviction that these will light their spirits through the mysterious shades; and at the foot of their coffins two more burning candles and a pasteboard placard on which a number is printed in large black type? Here the mourners of their respective dead are compelled to come and give publicity to their grief. It is not unusual to see a hundred bereft friends and relatives crowd into this chamber of death and piteously weep over the remains of their lost ones. The undertakers, who bring in the bodies from the hearse and arrange them on the biers, are too well inured to their work to be impressed with the meaning and sentiment of death. If the head of the body, during its jolting journey in the hearse, has fallen into an unseemly position, the assistant raises it, twists it, pushes it a little this way or that, with an indifference that seems brutal. More than pitiful is it to see poor little dried-up old women thus treated. These feelingless men, in trying to straighten out any dismantled article of clothing, often injure the appearance of the remains more than they improve them. The writer once saw one of these busy undertakers combing an elderly woman’s hair, which had become disarranged. It was monstrously apparent that he was not acquainted with the intricacies of her coiffure, for he loosened a switch and was unable to readjust it.

A set of electric wires communicating with the director’s office is fastened along the ceiling, from which depend cords at the ends of which are attached metal rings that are placed on the finger of every corpse to report anyone who might chance to have any life. It is related, upon authority not traceable, that years ago a Munich butcher came out of a trance in the middle of the night and found himself in the Deadhouse. The shock this discovery gave him is said to have entirely shattered his nerves and though still alive, lie is a mental wreck. It is safe to presume that a more sensitive being would actually have died from fright under like circumstances.

Perhaps the most pathetic sight of all is that of the dozen or more infants lying in a position upon the biers so evidently insecure as to suggest the terrible probability that they will roll off on to the hard floor. They are decked in flimsy filigree fabrics, reminding me of nothing so much as the cut tissue paper ornaments sometimes seen in provincial drug stores in this country.

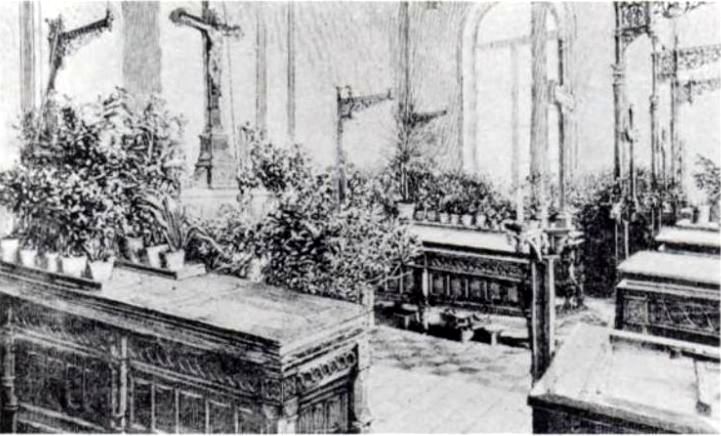

Further along to the eastward is another chamber devoted to the wealthy and aristocratic. This class lies in tastefully arranged bowers, and many of the corpses look peaceful, as though not only had their spirits departed with their mortal consent, but as though loving hands had done their best to render them presentable before intrusting them to the care of the state. Not infrequently the cold form of a general or a military man of high rank, dressed in his uniform, with his medals pinned on his coat and his trusty sword and crucifix in his clasped hands, may be seen in this apartment, which is more spacious than the other two mentioned.

I witnessed a touching incident one day while on one of my visits to the Southern Deadhouse in Munich. Two Americans, a brother and sister, came to the cemetery in a carriage to view the remains of an aunt with whom they had been “doing ” the Continent, and who had died at the Four Seasons Hotel the day before. Entering the passageway and turning to the right, after quitting their carriage, the two proceeded to the entrance of the death chamber, beside which stood a stoical official. In a few words addressed in German the young man communicated the object of his and his sister’s visit.

“Step inside,” said the official, coldly. “The body is No. 16.”

Whereupon he opened the door for them to enter.

“What did he say—No. 16?” asked the young girl, clinging desperately to her brother’s arm as they stepped into the room.

The odor of the disinfectants seemed to make her faint before she lifted her downcast eyes to see—what an instant later congealed her blood.

“Is this the Leichen-Haus?” she asked. “Oh, Henry, see those little babies'”

She turned away her face and leaned upon her brother’s arm, breathing nervously.

“Let us go back to the hotel,” urged the young man. “You are not strong enough to bear this. We will come to-morrow.”

“I am strong enough,” she answered, looking for the first time around the chamber. It seemed difficult for her to command herself; taking his hand, however, she glanced quickly on either side of the aisle, and said: “Come, the number is 16.”

They advanced together a few steps in silence, when the young woman suddenly ejaculated, throwing up her hands: “There!—there she is, Henry!”

She again averted her face, and made a movement as if to find protection and consolation in his arms, but, with a masterly effort, walked straight up to the coffin wherein her aunt was lying dead.

Here she broke down, and began to weep violently.

At length her brother succeeded in leading her back to the carriage. As they were going out I overheard her say: “Let us leave Munich as soon as possible. I cannot bear the thought of your possibly dying and being taken to this awful place.”

Making inquiries, I learned from the proprietor of the hotel where they stopped that the young man and his sister left for America immediately after the burial of her aunt.

Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, Volume 33, 1892: p. 459-462

A few points:

First, the English and the Americans were repulsed by the idea of a loved-one’s remains being exposed to the curious gaze of the general public. The Germans viewed the spectacle either as a jolly day out or, if they were visiting the corpse of someone they knew, as a wake or a viewing at a funeral home. I’ve posted previously on the idea of establishing similar waiting mortuaries in Connecticut, which, given the American prejudice, seemed doomed to fail.

Second, sanitary inspectors in New York and London reported the same issue with the poor keeping their dead at home long past their six-foot-under date. There is a stomach-churning passage on the evils of this practice in The Victorian Book of the Dead.

Third, it is stated in other sources that the waiting mortuaries were kept quite warm, ostensibly to aid in the resuscitation of the dead. There may have been, another, unstated reason: to hasten decomposition, considered the only reliable sign of death.

Fourth, it was the view of many medical men that of all the corpses who passed through the waiting mortuaries, not a single one was ever resuscitated. However, an author passionately interested in preventing premature burial refuted this with some vague statistics:

We are told repeatedly by the opponents of burial reform that there never has been an authenticated case of resuscitation in a mortuary in Germany. Clearly such persons must have been misinformed, for in the report of the Municipal Council of Paris for 1880, No. 174, page 84, there appears a letter from Herr Ehrhart, Mayor of Munich, dated May 2nd, 1880, in which is the following sentence: ‘The lengthy period during which these establishments (the mortuaries) have been utilised, the order which has always prevailed, the manner in which the remains are disposed and adorned, the resuscitation of some who were believed to be dead (the italics are mine) have all contributed to remove any sentimental objections to these establishments.’

In addition I find the following statement published on page 182 of Gaubert’s work, Les Chambres Mortuaires d’Attente: ‘We have collected in Germany fourteen cases of apparent death followed by return to life in mortuaries, in spite of all that has been done for the prevention of such occurrences.’

“Premature Burial and the Only True Signs of Death,” Basil Tozer, in The Twentieth Century, 1907, p. 558

One of these stories from Gaubert had a tragic ending:

A little child, five years old, was carried to the Leichenhauser, and the corpse was deposited as usual. The next morning a servant from the mortuary knocked at the mother’s house, carrying a large bundle in his arms. It was the resuscitated child, which she was mourning as lost. The transports of joy she experienced were so great that she fell down dead. The child came to life in the mortuary by itself, and when the keeper saw it, it was playing with the white roses which had been placed on its shroud. Premature Burial and how it May be Prevented, William Tebb, and Col. Edward Perry Vollum, M.D., Second Edition, Walter R. Hadwen, M.D. 1905, p. 348-9

One supposes that the mother of the child was not so fortunate as to come back to life under her shroud of roses…

Other tales from the Munich Deadhouse? Pull the bell-cord to send a signal to Chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com. I’ll be napping in the guard-room.

Mrs Daffodil tells a chilling story of a not-quite dead corpse at a waiting mortuary–you’ll find a picture of one of the Munich dead-houses as it looks today.

Further reading:

Premature Burial and how it May be Prevented, William Tebb, and Col. Edward Perry Vollum, M.D., Second Edition, Walter R. Hadwen, M.D. 1905, available on Google Books and Buried Alive, by Jan Bondeson.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.