The Passing of the Christmas Ghost Story

The Passing of the Christmas Ghost Story

The Christmas ghost story of the nineteenth-century magazines and newspapers was as much a part of holiday tradition as holly, plum pudding, and carollers. Dickens popularized it; hacks hackneyed it; M.R. James brought it to the pitch of paranormal perfection. But by the time of this piece, every possible change had been rung on the Christmas ghost story clichés and the ghost story had been supplanted by more modern entertainments such as bridge and mah-jongg.

THE PASSING OF THE CHRISTMAS GHOST STORY

BY STEPHEN LEACOCK

IT is a nice question whether Christmas, in the good old sense of the term, is not passing away from us. One associates it somehow with the epoch of stage-coaches, of gabled inns and hospitable country homes with the flames roaring in the open fireplaces. To appreciate a Christmas gathering one must have fought one’s way to it on horseback through ten miles of driving snow, or ridden in an ancient closed coach wheel-deep in melting slush. To arrive off a suburban trolley, punctual to the minute, won’t do. Somehow the magic is out of it. I often think that half the charm of Christmas, in literature at least, lay in the rough weather and in the physical difficulties surmounted by the sheer force of the glad spirit of the day. Take, for example, the immortal Christmases of Mr. Pickwick and his friends at Dingley Dell and the uncounted thousands of Christmas guests of that epoch of which they were the type. The snow blustered about them. They were red and ruddy with the flush of a strenuous journey. Great fires must be lighted in the expectation of their coming. Huge tankards of spiced ale must be warmed up for them. There must be red wine basking to a ruddier glow in the firelight. There must be warm slippers and hot cordials and a hundred and one little comforts to think of as a mark of gratitude for their arrival; and behind it all, the lurking fear that some fierce highwayman might have fallen upon them as they rode in the darkness of the wood.

Take as against this a Christmas in a New York apartment with the guests arriving by the subway and the elevator, or with no greater highwayman to fear than the taxicab driver. Warm them up with spiced ale? They’re not worth it.

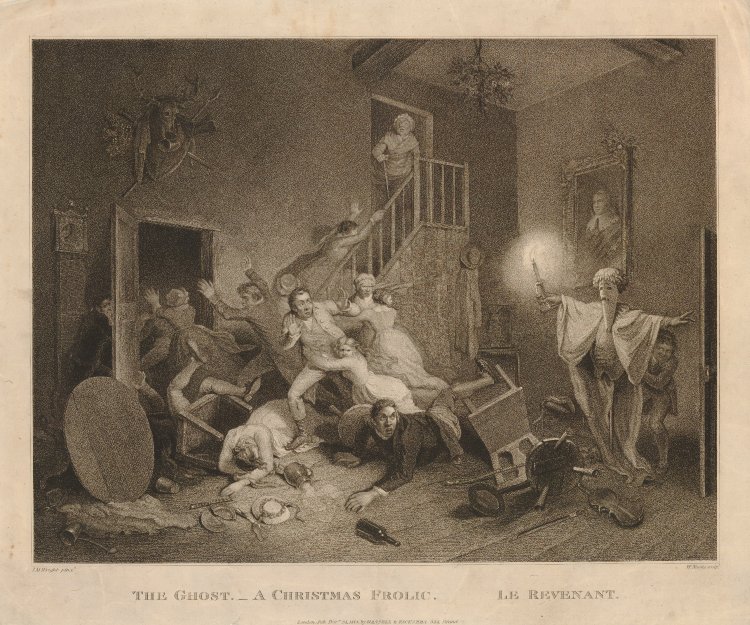

Can one wonder, then, that the older “literature of Christmas” is passing away? And most of all, the good old Christmas ghost story, parent of a thousand terrors. How well one recalls its awful apparatus—its “figures” and its “apparitions”, the “hollow voice” in which they spoke and the way in which, as the culminating terror, the figure “disappeared through the wall”! A humble trick it seems in these days to eyes that have watched Charlie Chaplin run up the side of a ten-story building and disappear into the sky.

Yet the people of the Victorian age, when ghost stories were ghost stories, loved nothing better than to get round a blazing fire as the night grew late and listen to a tale of “apparitions” and “figures” till even the stoutest of them took up his tallow candle to go to bed in a fit of the shudders, or, more dreadful and more delicious still, to read the awful tale in bed itself and by the uncertain light of the taper.

How well one recalls the opening and the setting of such an old-time ghost story.

“I am not what one would call a nervous man”, so the story used to begin, “yet there was something in the gloomy aspect of Buggam Grange, as one approached it from the dark avenue of silent spruce trees, that might well strike a chill, etc., etc.”

And how well one remembers this Buggam Grange! Evening is always “just falling” as one approaches it. The wind is “soughing” among its ancient chimneys. The house is wrapped in darkness save for a dim light here and there that struggles (I think “struggles” is the word) through the casement of a closed window. The “East Wing”—-the very name invites a shudder at once— stands gloomy and untenanted.

Such is Buggam Grange as we approach it upon our wearied horse. No, we are not nervous but Buggam Grange more or less “puts us to the bad” at sight. Yet imagine how different if we came buzzing up to Buggam Grange in a hundred-horsepower car: if Buggam Grange had electric light streaming out of its windows. Moaning of the wind! One would never hear it in the noise of the car. Or what if one did? One would merely ask to use the telephone for a minute and call up the emergency plumber of Buggam Hampstead and say: “Hullo, this is Buggam Grange speaking. The wind is soughing rather badly round one of our chimney tops. Will you please send up a man? Thank you.”

But in the days of the great darkness, before electricity was, Buggam Grange was a fearsome place indeed. Note our mode of entry to it. The door is unchained and we are admitted by a “solitary servant”; he is the “faithful butler” of the Buggam family: he has been in their service as boy and man for fifty years: he shakes his aged head with mournful foreboding as he lights us to our room in the dreaded East Wing. No one has slept in it for fifty years: none, in fact, since that dreadful night fifty years ago—and it was, by the strangest of coincidences, also a Christmas Eve—when Sir Duggam Buggam stabbed his best friend in the Tower room over a game of cards. If it had been auction bridge we could have understood it, if he had stabbed all his best friends. But when we remember it was cribbage, it seems hard to understand. Yet they hanged Sir Duggam for his crime at the assizes fifty years ago, and the villagers in Buggam Hampstead still tell strange stories of lights seen and voices heard in the East Wing of the Grange at Christmas time!

Can you wonder that when we are lighted to bed in that very Tower room, and remember this is Christmas Eve—exactly fifty years after the murder, not forty-nine, fifty—something nearly approaching to a shudder goes through us? As for that aged butler who says good night to us with “another melancholy shake of his head” (it is his one stunt), any reader of Christmas ghost stories knows what happens to him. He will be found dead, of course, next morning, stretched upon the floor of his pantry. Don’t ask me what is going to kill him. It will never be known. That was the dreadful thing about these Buggam Grange stories. There was no explanation given. The faithful butler was found dead stretched at full length (not half-length or foreshortened in any way, full length) upon the floor. These, one must remember, were the days before Sherlock Holmes. Sherlock would have made short work of the butler. He would have tracked the marks that his boots had made on the cement floor of the pantry, and “solved” him in no time.

But I am anticipating in talking of the dead butler. He is not found till the morning. Let us turn to consider the things that used, in the old-fashioned ghost stories, to happen to ourselves in the haunted room in the East Wing. How familiar all the old mechanism sounds: and how silly it has all grown in the bright light of electricity.

We try in vain to compose ourselves to sleep. Somehow we can’t sleep. Can one really wonder at it? In a damp old room with the wind soughing all over the place and the casement rattling and our ghastly “night light” (an invention of the devil used in the Victorian Age) throwing vast flickering shadows upon the ceiling. And the tapestry against the walls— I forgot the tapestry—moving slightly in the night wind! Put a modern reader in a room with those things and he’d leap out of bed in a frenzy, turn on the electric light, and grab the telephone and call for two plumbers and an upholsterer.

But in the Victorian days of the ghost story these things were denied. We had to lie in bed and tremble until at last we fall into a “fitful slumber”.

Do we know how long we have slept? We don’t. All that we know is that we are awakened by a sound that comes “from behind the wainscot”—a groaning. Our night light has flickered out. The room is in darkness and there is no electric switch. And someone is groaning behind the wainscot! We are not, generally speaking, a nervous man, but we confess now to “a feeling of apprehension”. Oh, yes.

We lie there. We have to: there is nothing else that we can do. And then somehow we become aware of a “presence” in the room. We do not see it or hear it or smell it, but we “become aware of it”. This presence which figured in all the ghost stories of the old days, has now been overwhelmed and forgotten in the litter of new psycho-spiritual jargon: it has been replaced by “phantasms” and “phantograms” and such. But I do believe it was worse and more terrible when it was labeled simply a “presence”. And we have become aware of it! The only thing is, has it become aware of us? Great Heavens, let us hope it hasn’t.

Ah, but it has, it has! Look what happens next! It is now no longer merely a “presence”. It has become a “figure”. This is worse. A “figure”, thin and impalpable as the night air, is moving about the room. It is illuminated by a “spectral light”. It moves nearer to our bedside. It extends its hand. Oh, help! And now it is no longer a “figure”. It has become an “apparition”—look! It is the apparition of Sir Duggam Buggam! The face is “grave and sad”. Apparitions’ faces always are: it is something in the life they lead that does it. The apparition points with its shadowy hand to the ghastly mark about its neck, the mark left by the hangman’s noose. We can feel our hair rise on end, on both ends, and then — “a prolonged and ghastly shriek is heard to resound from somewhere in the house below”.

This is enough. We quit. In the words of the original stories “our senses leave us” and we “know no more”.

When we awake, the “bright sun” is streaming in at the windows, and the birds (who would have thought that there were birds at Buggam Grange!) are singing outside the window.

“Workmen entering the house in the morning” (luckily they never went on strike then) find the body of the butler. Then the whole ghastly story comes out. Sir Duggam was innocent of the “foul deed”. It was the butler, then a young man of twenty-five, who had stabbed the guest for the sake of the gold piled upon the cribbage table. Sir Duggam was found, insensible still from drink, beside the body. His protests were in vain. He was hanged. Note that in Victorian literature the fact that Sir Duggam was “insensible from drink”—now called “spiflocated”— was not held to his discredit. The butler’s confession hidden away in a drawer of his pantry made all clear. As to what killed the butler, or who gave the shriek, or what the apparition was doing in the room, don’t ask me. These things came and went as vaguely and as inconsistently as the flickering of the night light. Explanations only spoil a story, anyway.

Such was the kind of stuff at which the Victorian reader loved to shudder. I have before me as I write a little, forgotten volume published in 1852, and labeled the “Night Side of Nature” by Catherine Crowe. A whole generation has shivered over its pages, blown out its bedside candle, and buried its head under the clothes in fear. Miss Crowe—or no, she must have been Mrs. Crowe; such a woman would have been snapped up like Scheherezade—spares her readers no horror. She won’t even label her characters by their names in ordinary Christian fashion. Here, for instance, is a dreadful tale concerning “the uncle of a Greek gentleman, Mr. M—, traveling in Magnesia”. I confess that the very name is too much for me. I admit that I’d hate to be away off in the heart of “Magnesia” with a Greek called M—. This story (I dare not read it, the beginning is enough) is in a chapter headed “Troubled Spirits”. What do you know about that? And here is another chapter called “Haunted Houses”, and a still more terrible looking one headed “Miscellaneous Phenomena”. No man I think can be blamed for admitting that he lives in deadly fear of miscellaneous phenomena. We all do.

And now why is it that the ghost story should have passed away, or rather, why did it flourish just at the time when it did? Here, I think, is the reason. The ghost story flourished best at that period (the middle of the nineteenth century) because at that period people had lost the belief in ghosts, at least as a serious, everyday part of their creed. The wonderful revelations of natural science were hurrying the thinking world in a cheap and vainglorious materialism: an apparition was dismissed as a mere “phosphoresence”—a vastly different thing; a noise behind a wainscot was a rat; a “sense of melancholy foreboding” was a stomachache. Everything was known and labeled and assigned to its true place in the universe—except perhaps two or three awkward little problems which were bunched together as the “unknowable” and shoved into a corner.

In such a world there was no room for ghosts. Hence a ghost story was not a true story. It was a wild reversion of the imagination to the forgotten terrors of the past. In earlier days, in the middle ages, let us say, this was not so. A ghost story was a true story. It might be very terrible, yet it was after all merely a statement of terrible fact, not a wild terror of the imagination. If a man related that an evil spirit had appeared to him in the night, he meant exactly what he said. It was a plain statement of a distressing fact. It was just as if a man said nowadays that his tailor had turned up at his house in the day—the same sort of thing. It was a bothersome thing and might mean a lot of trouble to come, but there was nothing in the relation of it that involved the wide-eyed terror of the nineteenth century. The materialist, in his horrors of the night, paid the penalty of his vainglory by day.

And now the scene has changed again. The ghosts have all come back. They are buzzing round us all the time. Oliver Lodge and Conan Doyle have seen bunches of them. They think nothing of them. It appears that one can talk to them by telepathy,or by table-rapping, or with a ouija board or in a dozen ways: and then when one does, their poor minds are so enfeebled from living behind the wainscot that one can feel nothing but pity for their simple talk. One respects them in a way: they are a religious lot: they like to talk of how bright and beautiful it is behind the wainscot, but in point of intellect they are—there is only one word for it—”mutts”.

As to a ghost story as an engine of terror under such circumstances, the mere idea becomes ludicrous. The modern guest in the East Wing would come calmly down to breakfast and say as he took his porridge—”There was an apparition in my room last night”, in the same way that he would have spoken if there had been a bat in it. “Oh, I do hope it didn’t disturb you?” says the hostess at the coffee pot. “Oh, not at all, I chased it out with a tennis racket.” “Poor things”, murmurs the lady, “but we don’t like to get rid of them altogether. Teddy and Winifred are making a little collection of notes about them and their father’s going to send it to the Psychical Research. But I do dislike the children sitting up at night in the ruined tower in the wood. It’s so damp for them. Two lumps?”

So the ghost story is dead. Let it rest in peace—if it can.

The Bookman,Vol. 50, 1920

Of course, today the ghost story, or its modern equivalent, the reality TV ghost-hunting show, is anything but dead. It’s always seemed to me that the the more complex the world–the more scientific and technological it becomes–the more some individuals retreat into the very human desire for mystery, burying themselves in the cliches of orb photos, EVP recordings, or EMF meter readings.

The Victorians would have pointed to a decline in education as a key factor in this interest in ghosts. In vintage reports of the paranormal, there is often editorial puffing about how incredible it is in this land of quality education and modern progress, that anyone would believe in ghosts! And it is predicted that education and electricity will soon drive out ghost-belief in rural areas.

Perhaps the decay of our educational system has fueled a flourishing ghost industry. It may be that belief in ghosts is supplanting traditional religion in some quarters (although demonologists are certainly trending.) I keep hoping wistfully that it is a dying fad du jour, like an ectoplasmic version of the hula hoop, even though Ghost Hunters has lasted a good deal longer than the pet rock.

Much as I would like to see reality ghost TV supplanted by films of Robert Lloyd Parry reading M.R. James, it is probably premature to toll the passing bell for the demise of the Christmas ghost story. And there will always be mysteries, despite bad TV, ghost phone apps, and teen girl exorcists.

Just now I’m ringing off for a bit to celebrate the holidays, but will return in the new year, as relentlessly informative as always, to share more ghosts, curiosities, and wonders.

Whatever midwinter holiday you celebrate, I wish you peace, plenty, and the blessings of the season.

[Visit Mrs Daffodil for another comic skewering of Christmas Ghost story conventions by Jerome K. Jerome. Mrs Daffodil also reports on “Christmas Ghosts Doomed by Bridge in Britain.”

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.