The Masque of the Black Death: Paris in the Time of Cholera

The Cholera Galopade

As we head into August, I am reminded of how summer was commonly dreaded as cholera-season. I have previously covered the grim humor of cholera jokes. Here we return to the theme, with a look at the Second Cholera Pandemic in Paris. Eye-witness accounts from the front lines of any tragic event are always fascinating. Poet Heinrich Heine was in Paris as a journalist in 1832 and gives a vivid description of Death at the Carnival, while this longer account comes from, shall we say, a hands-on narrator.

March 1832 You will see by the papers, I presume, the official accounts of the cholera in Paris. It seems very terrible to you, no doubt, at your distance from the scene, and truly it is terrible enough, if one could realise it any where—but no one here thinks of troubling himself about it; and you might be here a month, and if you observed the people only, and frequented only the places of amusement and the public promenades, you might never suspect its existence. The month is June-like—deliciously warm and bright, and the trees are just in the tender green of the new buds; and the exquisite gardens of the Tuileries are thronged all day with thousands of the gay and idle, sitting under the trees in groups, and laughing and amusing themselves as if there was no plague in the air, though hundreds die every day; and the churches are all hung in black, with the constant succession of funerals, and you cross the biers and hand-barrows of the sick hurrying to the hospitals at every turn, in every quarter of the city. It is very hard to realise such things, and, it would seem, very hard even to treat it seriously.

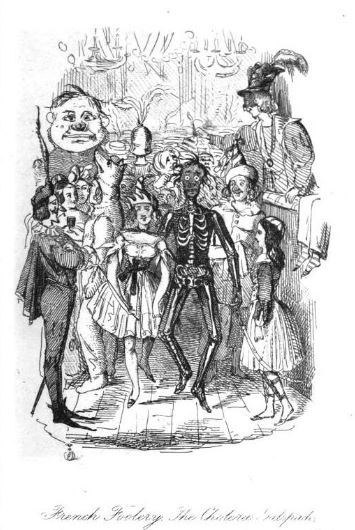

I was at a masque ball at the “Theatre des Varieties” a night or two since, at the celebration of the Mi-careme. There were some two thousand people, I should think, in fancy dresses; most of them grotesque and satirical; and the ball was kept up till seven in the morning with all the extravagant gaiety and noise and fun with which the French people manage such matters. There was a cholera-waltz and a cholera-gallopade; and one man, immensely tall, dressed as a personification of the cholera, with skeleton armour and blood-shot eyes, and other horrible appurtenances of a walking pestilence. It was the burden of all the jokes, and all the cries of the hawkers, and all the conversation. And yet, probably, nineteen out of twenty of those present lived in the quarters most ravaged by the disease, and most of them had seen it face to face, and knew perfectly its deadly character.

As yet, the higher classes of society have escaped. It seems to depend very much on the manner in which people live; and the poor have been struck in every quarter, often at the very next door to luxury. A friend told me this morning that the porter of a large and fashionable hotel in which he lives had been taken to the hospital; and there have been one or two cases in the airy quarter of St. Germain. Several medical students have died, too, but the majority of these live with the narrowest economy, and in the parts of the city the most liable to impure effluvia. The balls go on still in the gay world, and I assume they would go on if there were only musicians enough left to make an orchestra, or fashionists to compose a quadrille.

As if one plague was not enough, the city is all alive in the distant faubourgs with revolts. Last night the rappel was beat all over the city, and the National Guard called to arms and marched to the Porte St. Denis and the different quarters where the mobs were collected. The occasion of the disturbance is singular enough. It has been discovered, as you will see by the papers, that a great number of people have been poisoned at the wine-shops. Men have been detected, with what object Heaven only knows, in putting arsenic and other poisons into the cups and even into the buckets of the water-carriers at the fountains. Several of these empoisonneurs have been taken from the officers of justice and literally torn limb from limb, in the streets. Two were drowned yesterday by the mob in the Seine, at the Pont-Neuf. It is believed by many of the common people that this is done by the government, and the opinion prevails sufficiently to produce very serious disturbances. They suppose there is no cholera, except such as is produced by poison; and the Hotel Dieu and the other hospitals are besieged daily by the infuriated mob, who swear vengeance against the government for all the mortality they witness.

I have just returned from a visit to the Hotel Dieu—the hospital for the cholera. I had previously made several attempts to gain admission, in vain, but yesterday I fell in, fortunately, with an English physician, who told me I could pass with a doctor’s diploma, which he offered to borrow for me of some medical friend. He called by appointment at seven this morning, to fulfil his promise. It was like one of our loveliest mornings in June—an inspiriting, sunny, balmy day, all softness and beauty, and we crossed the Tuileries by one of its superb avenues, and kept down the bank of the river to the island. With the errand on which we were bound in our minds, it was impossible not to be struck very forcibly with our own exquisite enjoyment of life. I am sure I never felt my veins fuller of the pleasure of health and motion, and I never saw a day when everything about me seemed better worth living for. The superb palace of the Louvre, with its long facade of nearly half a mile, lay in the mellowest sunshine on our left,—the lively river, covered with boats, and spanned with its magnificent and crowded bridges on our right,—the view of the island with its massive old structures below, — and the fine old gray towers of the church of Notre Dame, rising dark and gloomy in the distance—it was difficult to realise anything but life and pleasure. That under those very towers which added so much to the beauty of the scene, there lay a thousand and more of poor wretches dying of a plague, was a thought my mind would not retain a moment.

A half hour’s walk brought us to the Place Notre Dame, on one side of which, next this celebrated church, stands the Hospital. My friend entered, leaving me to wait till he had found an acquaintance, of whom he could borrow a diploma. A hearse was standing at the door of the church, and I went in for a moment. A few mourners, with the appearance of extreme poverty, were kneeling round a coffin at one of the side-altars, and a solitary priest, with an attendant boy, was mumbling the prayers for the dead. As I came out, another hearse drove up, with a rough coffin scantily covered with a pall, and followed by one poor old man. They hurried in; and, as my friend had not yet appeared, I strolled round the square. Fifteen or twenty water-carriers were filling their buckets at the fountain opposite, singing and laughing, and at the same moment four different litters crossed towards the Hospital, each with its two or three followers, women and children or relatives of the sick, accompanying them to the door, where they parted from them, most probably, forever. The litters were set down a moment before ascending the steps, the crowd pressed around and lifted the coarse curtains, farewells were exchanged, and the sick alone passed in. I did not see any great demonstration of feeling in the particular cases that were before me, but I can conceive, in the almost deadly certainty of this disease, that these hasty partings at the door of the Hospital might often be scenes of unsurpassed suffering and distress. I waited, perhaps, ten minutes more for my friend. In the whole time that I had been there, ten litters, bearing the sick, had entered the Hotel Dieu.

As I exhibited the borrowed diploma, the eleventh arrived, and with it a young man, whose violent and uncontrolled grief worked so far on the soldier at the door, that he allowed him to pass. I followed the bearers up to the ward, interested exceedingly to see the patient, and desirous to observe the first treatment and manner of reception. They wound slowly up the staircase to the upper story, and entered the female department—a long, low room, containing nearly a hundred beds, placed in alleys scarce two feet from each other: nearly all were occupied; and those which were empty, my friend told me, were vacated by deaths yesterday.

They set down the litter by the side of a narrow cot with coarse but clean sheets, and a Soeur de Charite, with a white cap and a cross at her girdle, came and took off the canopy. A young woman of apparently twenty-five was beneath, absolutely convulsed with agony. Her eyes were started from the sockets, her mouth foamed, and her face was of a frightful, livid purple. I never saw so horrible a sight. She had been taken in perfect health only three hours before, but her features looked to me marked with a year of pain. The first attempt to lift her produced violent vomiting, and I thought she must die instantly. They covered her up in bed, and, leaving the man who came with her hanging over her with the moan of one deprived of his senses, they went to receive others who were entering in the same manner. I inquired of my friend, how soon she would be attended to. He said, “Possibly in an hour, as the physician was just commencing his rounds.” An hour after, I passed the bed of this poor woman, and she had not yet been visited. Her husband answered my question with a choking voice and a flood of tears.

I passed down the ward, and found nineteen or twenty in the last agonies of death. They lay quite still, and seemed benumbed. I felt the limbs of several, and found them quite cold. The stomach only had a little warmth. Now and then a half groan escaped those who seemed the strongest, but with the exception of the universally open mouth and upturned ghastly eye, there were no signs of much suffering. I found two, who must have been dead half an hour, undiscovered by the attendants. One of them was an old woman, quite grey, with a very bad expression of face, who was perfectly cold—lips, limbs, body and all. The other was younger, and seemed to have died in pain. Her eyes looked as if they had been forced half out of the sockets, and her skin was of the most livid and deathly purple. The woman in the next bed told me she had died since the Soeur de Charite had been there. It is horrible to think how these poor creatures may suffer in the very midst of the provisions that are made professedly for their relief. I asked why a simple prescription of treatment might not be drawn up by the physician, and administered by the numerous medical students who were in Paris, that as few as possible might suffer from delay. “Because,” said my companion, “the chief physicians must do everything personally to study the complaint.” And so, I verily believe, more human lives are sacrificed in waiting for experiments than ever will be saved by the results.

My blood boiled from the beginning to the end of this melancholy visit. I wandered about alone among the beds till my heart was sick, and I could bear it no longer, and then rejoined my friend, who was in the train of one of the physicians making the rounds. One would think a dying person should be treated with kindness. I never saw a rougher or more heartless manner than that of the celebrated Dr. __ at the bed-sides of these poor creatures. A harsh question, a rude pulling open of the mouth to look at the tongue, a sentence or two of unsuppressed comment to the students on the progress of the disease, and the train passed on. If discouragement and despair are not medicines, I should think the visits of such physicians were of little avail. The wretched sufferers turned away their heads after he had gone, in every instance that I saw, with an expression of visibly increased distress. Several of them refused to answer his questions altogether.

On reaching the bottom of the Salle St. Monique, one of the male wards, I heard loud voices and laughter. I had heard much more groaning and complaining in passing among the men, and the horrible discordance struck me as something infernal. It proceeded from one of the sides to which the patients had been removed who were recovering. The most successful treatment had been found to be punch —very strong, with but little acid; and, being permitted to drink as much as they would, they had become partially intoxicated. It was a fiendish sight, positively. They were sitting up, and reaching from one bed to the other, and with their still pallid faces and blue lips, and the hospital dress of white, they looked like so many carousing corpses. I turned away from them in horror.

I was stopped in the door-way by a litter entering with a sick woman. They set her down in the main passage between the beds, and left her a moment to find a place for her. She seemed to have an interval of pain, and rose up one hand and looked about her very earnestly. I followed the direction of her eyes, and could easily imagine her sensations. Twenty or thirty death-like faces were turned towards her from the different beds, and the groans of the dying and the distressed came from every side, and she was without a friend whom she knew: sick of a mortal disease, and abandoned to the mercy of those whose kindness is mercenary and habitual, and, of course, without sympathy or feeling. Was it not enough alone, if she had been far less ill, to embitter the very fountains of life, and make her almost wish to die? She sank down upon the litter again, and drew her shawl over her head.

I had seen enough of suffering; and I left the place. On reaching the lower staircase, my friend proposed to me to look into the dead-room. We descended to a large dark apartment below the street level, lighted by a lamp fixed to the wall. Sixty or seventy bodies lay on the floor, some of them quite uncovered, and some wrapped in mats. I could not see distinctly enough by the dim light to judge of their discolouration. They appeared mostly old and emaciated. I cannot describe the sensation of relief with which I breathed the free air once more. I had no fear of the cholera, but the suffering and misery I had seen oppressed and half smothered me. Everyone who has walked through a hospital will remember how natural it is to subdue the breath, and close the nostrils to the smells of medicine and the close air. The fact too, that the question of contagion is still disputed, though I fully believe the cholera not to be contagious, might have had some effect. My breast heaved, however, as if a weight had risen from my lungs, and I walked home to my breakfast, blessing God for health with undissembled gratitude. Pencillings by the Way, Nathaniel Parker Willis 1836

We have met Willis, the death-tourist, before, in a story about composting the dead in Naples. The man must have led a charmed life. There was a horrific outbreak of cholera in Naples during his visit, but he went there anyway and seemed to think it barely worth mentioning. In this Parisian episode, not only does Willis wantonly and deliberately borrow a doctor’s diploma so he can visit the cholera hospital, he touches patients “in the last agonies of death,” finding them, quelle surprise! “quite cold. The stomach only had a little warmth.”—unlike Willis’s blood, which was boiling at the attitudes of the doctors. French physicians believed cholera to be a disease of the poor, who were more to be censured than pitied for their dirty vices and habits. It is no wonder they were dismissive of their dying patients. And it was no wonder that the ball-goers danced and frolicked—any moment could be their last. As Willis describes, the young woman in perfect health was on her deathbed in a matter of hours. The “livid and deathly purple” he notes was a dreadful symptom of cholera: rapid dehydration led to the darkening of the skin from blue to black, hence the disease was sometimes called “The Black Plague” or “Black Cholera.”

As I mentioned in the previous article about the Naples death-pits, Willis was a close friend of Edgar Allan Poe. These letters, which he dashed off and sent to the newspapers as ephemeral sketches, were published in various newspapers as early as 1832. While his book, which opens with this account of his travels among the cholera-afflicted, was not published until 1835, perhaps Willis privately shared with Poe his experiences at that fateful Carnival when the disease first attacked Paris. This article suggests that the cholera episode, published in 1832, in the New-York Mirror inspired parts of “The Masque of the Red Death,” (1842.)

Any other eye-witness accounts of the cholera-waltz or the cholera-gallopade? chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.