The Plague Shawl

Today’s post returns to one of my favorite themes: deadly clothing. We have covered the perils of poisoned stockings and noxious hairpieces. The history of disease is filled with cases of contagion spread by textiles:

In 1665 at Eyam, in Derbyshire, a tailor received a flea-infested shipment of cloth from London. He was dead of the plague within a week. Heroically, the villagers voluntarily quarantined themselves to keep the disease from spreading—at a fearful cost: at least half of Eyam’s inhabitants died.

At Fort Pitt, in 1763, two Native American chiefs were given blankets and a handkerchief from smallpox victims, possibly causing an outbreak of the disease and extensive casualties among the Indians.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1838 story, “Lady Eleanore’s Mantle” tells of a richly embroidered cloak believed to have brought the smallpox to Boston. The story is fiction, but Hawthorne’s readers’ belief in an infected cloak causing an epidemic was not.

In 1872, Ipswich was hit by an outbreak of smallpox, blamed again on textile infection:

During Christmas week two imported cases occurred…a young man brought a bundle of infected linen with him from London, and had it washed in Ipswich. Twelve days after, the servant who washed the linen showed symptoms of small-pox. In another case, a woman, who had been at Highgate Hospital, brought with her a shawl which she had worn during convalescence, but had not been disinfected; and in fourteen days her sister, who washed the shawl, was attacked, and a boy also in a house to which the sister went before the rash appeared upon her. This case might also have been caused by the infected shawl. The disease shortly afterwards broke out in Harwich and was very fatal, as 24 per cent. of the cases admitted died in the hospital. The Sanitary Record, Vol. 8, 1878

In a very recent case, in September of 2012, a young girl contracted the plague from her sweatshirt which had been laid by a decomposing (and flea-ridden) squirrel.

Then there is this story from 1895 illustrating the improbably long shelf-life of smallpox:

TENACITY OF GERMS

How an Old Lady and Her Little Shawl Carried Death With Them.

The tenacity and virility of smallpox germs are to the medical fraternity one of the wonders of contagion, and were never made apparent so startlingly as a few years ago in the little village of Hector, this state, says the New York Sun. This is an isolated place, being at the time of the smallpox epidemic there twenty miles from any railroad, and its people rarely traveled far from home, and few strangers were visitors there. Early in the fall smallpox broke out in the village. The disease was not known to be anywhere in the vicinity. How it happened to appear there was a mystery that remained unsolved for months, but was at last cleared up through the investigation and inquiry of Dr. Purdy of Elmira.

Dr. Purdy learned that one day in the winter preceding the breaking out of smallpox in Hector a passenger on an Erie railway train was taken violently ill just after leaving Salamanca, and a physician who was on board the train discovered that the passenger had the smallpox. When this became known the other passengers in the car hurriedly left it for another one. The car containing the smallpox victim was placed on a siding when the train reached Hornellsville, where it was quarantined.

Among the passengers who left the car when the case was made known was an old lady who had a ticket for Elmira. Her seat had been the one behind the one where the man with the small-pox sat. She had with her a small shoulder shawl, which had hung on the back of the seat ahead of her. When she left the train at Elmira she placed the shawl in her hand satchel. At Elmira she took a Northern Central train for Watkins, the nearest station to Hector, to which place she was going on a visit to her son’s family. She remained there until the following fall when she was driven by her son to visit another son some miles distant. The day was extremely cold, and her son’s ears being in danger of freezing she took the shoulder shawl from her satchel, where it had been ever since she put it away on leaving the Erie train at Elmira the previous winter, and wrapped it about his head.

A few days after the son returned home to Hector he became violently ill. Before it was known what his ailment was he was visited by various neighbors. Then his disease was pronounced smallpox, and it was such a malignant case that he died within a few days. The disease became epidemic and was not eradicated until the following summer. Every family in the village and immediate vicinity lost at least one member by the disease. That the first case originated from the germs collected by the shawl in the railroad car near Salamanca months before there can be no doubt. Idaho Register [Idaho Falls, ID] 15 February 1895: p. 6

I say “improbably long shelf-life” of smallpox, but the virus is capable of prolonged survival. Excavators in the crypt of Christ Church, Spitalfields, 1984-86, for example, took special precautions, not only against the lead dust from the coffins, but against potentially viable smallpox from dead victims of the disease buried there. And in 2011, an 1860s smallpox scab was siezed by the CDC from an exhibit at the Virginia Historical Society.

In Russia, the Plague of 1878-79 was reported to have had its origins in a lethal sweetheart’s souvenir.

A COSSACK FROM THE WAR

Brings to His Lady LoveA Costly Shawl Which She Wore Two Days,

Then Sickened and Died, and in this

Lies the Origin of the Present Russian Plague.

London, Feb. 3. The origin of the plague in Russia is thus given: A Cossack, returning from the war to Wetlisuka, brought his lady love a shawl which she wore two days and then sickened with all the symptoms of the plague and died. The following four days other members of her family died. The disease spread rapidly, the local authorities not paying any attention to it till half the inhabitants had died and the remainder were unable to bury them. Then, when the epidemic had assumed serious dimensions energetic means were taken for preventing its spreading, and strict quarantines were established: firstly in towns and villages, shutting off streets where the plague reigns from the rest of the place and secondly by surrounding the villages with troops, so that nobody is allowed to pass in or out.

The panic in Russia is almost incredible. Every class and station in life have petitioned for the entire cessation of all intercourse even postal communication between the rest of Russia and the Volga. Letters from Astrachan and Zaritzin are not received by persons to whom they are addressed. Some people even refuse to take money, fearing the germ of infection might be communicated through it. It is almost impossible to describe the terror which has taken possession of the people.

The Russian Sanitary Commission has proposed to shut off the Volga line from all intercourse with Western Russia and permit communication only under quarantine. Russian railway cars are not admitted to German territory. The export of grain from Poland will suffered severely from this restriction. The Roumanian government are discussing the expediency of prohibiting the transit of Russian provisions sent to victual the Balkan army.

(This appears to be a paraphrase of a New York Times article of 2 February 1879. It appeared in the Plain Dealer [Cleveland, OH] 3 February 1879: p. 1)

The Russian plague caused panic throughout Europe, which feared the spread of an epidemic on the scale of the Black Death. The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica observed that the Russian wave of the disease killed about 362 victims out of a population of about 1700.

It is, of course, impossible to tell if the story of the deadly shawl is more than a fanciful legend, although the story is repeated in a scholarly article: “The Russian Plague of 1878-79,” Hans Heilbronner, Slavic Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Mar., 1962), pp. 89-112 in the note on pp. 91-92.

A story was bandied about in 1879 that a Cossack, returning to Vetlianka from Turkish Armenia, brought a scarf to his fiancée as a present. She supposedly wore it for a few days, then developed fearful symptoms of an undiagnosed nature, and died within a few days. The members of her family contracted the same disease and so did some neighbors. Refugees from the village reportedly carried the affliction to other Volga towns and villages.

Strangely, the story is also the subject of a poem by Ohio poet Sarah Piatt

THE STORY OF A SHAWL

[1879.]

My child, is it so strange, indeed,

This tale of the Plague in the East, you read?

This tale of how a soldier found

A gleaming shawl of silk, close-wound,

(And stained, perhaps, with two-fold red)

About a dead man’s careless head

He took the treasure on his breast

To one he loved. We know the rest.

If Russia shudders near and far,

From peasant’s hut to throne of Czar

If Germany bids an armed guard

By sun and moon keep watch and ward

Along her line, that they who fly

From death, ah me ! shall surely die.

This trouble for the world was all

Wrapped in that soldier’s sweetheart’s shawl.

Pray God no other lovers bring

Some gift as dread in rose or ring.

Poems, Vol. II, Sarah Piatt (London: Longmans, Green and Co.) 1894

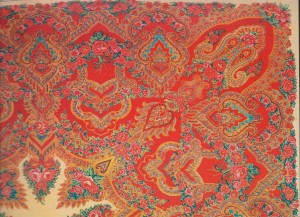

For the historical aspects of Russian shawl production, please see http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1563&context=tsaconf for “Luxury Textiles from Feudal Workshops: 19th Century Russian Tapestry-Woven Shawls” by Arlene C. Cooper of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.