“Uncanny Meteors:” Spook Lights in New Zealand

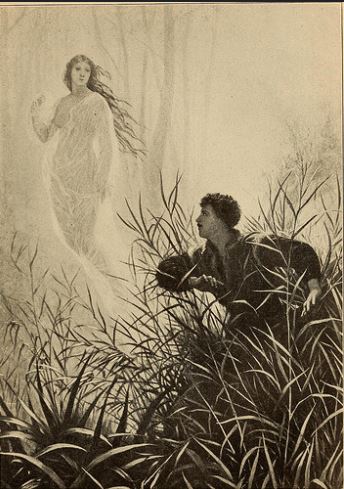

“Uncanny Meteors:” Spook Lights in New Zealand Lady Will-o-the-wisp. He’d follow her anywhere….

“Uncanny Meteors:” Spook Lights in New Zealand

It seems that the darkness of January always arouses my interest in stories of spook lights or mysterious fires. Today a gentleman from New Zealand tells us of his curious close encounter with “uncanny meteors” during a downpour. I’ve left in the first few paragraphs of technical explanation and literature review for completeness, but the actual story of the sighting may be found two paragraphs in.

Marsh-lights. By R. Coupland Harding.

Read before the Wellington Philosophical Society, 4th August, 1897.

The phenomenon of the ignis fatuus, will-of-the-wisp, or fool’s candle, seems to have excited interest in all ages. Literature, ancient and modern, abounds with references to the subject, and poets and moralists alike have found it an obvious image of those false lights in philosophy and religion which beguile the inquirer from the narrow paths of truth into the pitfalls of error and the gulfs of despair. Superstition has been busy with the meteor that, haunting graveyards and dangerous marshes, acts almost as if possessing life and volition. Those who have seen, and especially those who have attempted to follow, this “faithless phantom ” can well understand that in a pre-scientific age an imp of darkness was supposed to guide the erratic light, in following which so many have perished.

Having recently had, for the first time, an opportunity of observing this phenomenon, I looked up such authorities as I could discover, and have been surprised to find that marsh-candles, so long known and observed, are still the property of poetry and superstition. No accurate observations seem to be on record, and science as yet appears to have nothing to say on the subject. For instance, the “Encyclopaedia Britannica” dismisses it in a few lines. It “has given rise to much difference of opinion; Kirby and Spence suggest that it may be due to luminous insects; but this explanation will certainly not apply in all cases, and it is perhaps on the whole more reasonable to believe that the phenomenon is caused by the slow combustion of marsh-gas (methyl hydride).” That is all from this high authority. Turning to “Chambers’s Encyclopaedia,” I find a much longer, but still very vague, account, wherein I read, “The common hypothesis that the ignis fatuus is the flame of burning marsh-gas is untenable, for, although this gas is produced abundantly in many marshy places, it cannot ignite spontaneously.” Thus do authorities differ. In Chambers I read of a German who held the end of his cane in a will-of-the-wisp for a quarter of an hour and found that it was not perceptibly heated. From this crude experiment the writer infers that “the more plausible suggestion of phosphuretted hydrogen does not account for the fact observed by the German physicist, since no gas can burn without heat, and this gas has a very pungent and characteristic smell.” I can offer no opinion as to what the gas may be, but I think that these arguments have no force. It is impossible that a globule of gas which will burn for a quarter of an hour—perhaps for four times as long—before it is consumed could emit sufficient heat to perceptibly raise the temperature of a metal-shod walking-stick. The observer may not even have touched the bubble of gas—probably he did not—and even if the experiment was fairly tried it would have been as reasonable to expect the walking-stick to be warmed by contact with a glowworm. As for the smell, the peculiar condition of the gas which renders it luminous appears to prevent its free diffusion in the atmosphere — if sensible to smell the gas cannot be seen. I read further in the same paper of an experimenter lighting a piece of paper at a will-of-the-wisp. On what authority this amazing statement rests does not appear. It seems probable that there is more than one variety of ignis fatuus—some observers describe “bounding” ones, leaping 60 ft. or more at a time — but that any bubble of luminous gas floating in the atmosphere is of so high a temperature as this I do not believe. If it were, the farmer whose haystack is mysteriously burned need not suspect incendiarism if there is a swamp near at hand. In the case of a steady stream of natural gas issuing under pressure from a small orifice in the earth, and artificially ignited, it would be easy enough to light a piece of paper; but a burning jet of this kind is not the ignis fatuus.

On the morning of the 14th February last, between 3 and 4 o’clock, I found myself on the Ruataniwha Plains, several miles from Takapau. I had been walking for some hours, during one of the darkest nights I have ever known, and in steady rain. I had come through the Seventy-mile Bush from Dannevirke on one of the finest highways in New Zealand, but found quite a different state of things on the plain. The road was badly cut up by recent rains, great stones were strewn about, and it was more like a ravine than a roadway. In daylight there would have been no difficulty; in the dense darkness I found it unsafe to proceed. In fact, beginning to doubt whether I was on the right track, and fearing to go astray in the labyrinth of roads on the wide plain, I retraced my steps nearly a mile, remembering that I had not long before passed a gate, beyond which I had seen dimly a house, with lights twinkling from the windows. There, at any rate, when daylight came, I might make inquiry. By keeping near to the fence I found a foot-track in the grass, on which I could safely walk. I saw nothing either of gate or house, but soon became aware of two lights, apparently about a hundred yards away, beyond the fence. They did not seem quite steady, or I would have taken them for the lights I had previously seen. They were at about the level of my eyes, and remained steady when I stood still. Thinking there might be some illusion, I raised my glasses, which had become blurred with raindrops, but the lights remained. As I moved on they kept pace with me, and I realised what they were. I can scarcely account for the feeling of aversion with which they inspired me—insignificant gas-bubbles as they were. I found myself watching them instead of looking to my feet, and at length, being tired, I stood still. Attracted by a light on the ground, I looked down, and saw one of these horrible little bubbles disengaging itself from the sodden grass close to my feet, probably forced out of the soil by my weight. I had thus the opportunity of closely examining it. It was of a well-defined form, apparently cylindrical, rounded at the ends, just like the bubble in the glass tube of a spirit-level, only somewhat curved in shape, and about the size of a small bean. It shone with a lambent yellowish flame, brighter and more concentrated than the two floating beside me. It appeared to cling to the grass, but worked its way out slowly and steadily, with a wriggle almost like that of a living creature. I suppose I watched it for ten or fifteen seconds before it became free, when it rose so suddenly that the sight could not follow it. Looking up, I now saw three of my unwelcome companions instead of two—just like three candles or dim lamps in the distance. This effect of distance must surely have been an illusion; really I think they could not have been many inches away; but the bubble was now undefined in form, and proportionately fainter than when it escaped from the earth. I suspect that there must have been something in the condition of these gas-bubbles—perhaps their electrical state—that kept them self-contained, and prevented their mingling with the air. I went on, still accompanied by my familiars, till I came to a gate, but not the one I was seeking. I paused—so did they. I went through—they went before instead of keeping at my side. Soon I found myself on slippery clay, with a suspicious gleam of water ahead, the three lights still moving forward. I turned my back on them, returned to the road, and went on, when I found them at my side as before; but thereafter I paid little attention to them. Coming to the end of the fence, I knew I must have passed the house. I decided to wait, and did wait, for dawn—for a long hour. When I stopped I looked for my attendants, and they were not to be seen. They must have been visible quite a quarter of an hour, and have accompanied me nearly a mile. Their behaviour was exactly such as is described by poets and storytellers in literature familiar to us all. What was new to me, and unlike anything I have read or heard of, was the newborn will-of-the-wisp emerging from the ground. I should add that this did not occur in swamp- or bog-land, but on the margin of an ordinary grass paddock, on a plain consisting of shingle covered with no great depth of earth, and that the moisture of the soil was exceptional, owing to recent heavy rains. Kirby and Spence’s theory of luminous insects would not apply here. What I saw were luminous gas-bubbles, presumably from decaying organic matter; the light, I infer, resulted from slow combustion, necessarily at a low temperature, as the gas, which would not have filled a thimble, burned steadily for at least a quarter of an hour. According to Chambers, the impure hydrogen gas of marshes is not known to ignite spontaneously, and all attempts to imitate the phenomenon of the ignis fatuus have been unsuccessful. This seems to me to suggest some peculiar electrical condition of the gas as being the cause of the appearance.

The most puzzling feature of the will-of-the-wisp, so general as to have become typical, and which I had full opportunity of verifying, is its habit of closely accompanying or preceding a traveller while maintaining the illusion of being at a considerable distance. On this occasion, though the air was not calm, there was very little wind. I confess that I cannot account for the apparent attraction that caused these uncanny meteors to accompany me a mile in the darkness, and to go before me when I altered my course. I can well imagine how fatal this habit has proved in the case of many an unsuspecting wayfarer who has lost his way among marshes and old quarries. Fearful of losing sight of the “hospitable ray,” he has not looked to his feet, and has miserably perished in some deep pool or quaking bog, or has been dashed to death at the foot of a precipice.

Chambers says that the phenomenon was much more common and familiar in Europe a century ago than now—that as the country is drained and cultivated the marsh-lights disappear. If so, there is the more reason to carefully study this curious phenomenon when opportunity arises; and it is with the view of adding to the slender stock of information on the subject that I place these observations on record.

And incidentally I would remark on the curious Celtic superstition of “corpse-candles,” which are described as exactly such appearances as I saw last February. A large and yellow one is supposed to indicate the approaching death of an adult; a small bluish one that of a child; and both are sometimes seen together. They are supposed to leave the house of the person about to die, to follow the line taken by the body in the funeral procession, indicating every stoppage on the way, and disappearing at the site of the grave. As in all matters of common popular belief, there is a mass of testimony on the subject, not only of natives, but of tourists and others. Cases are known of visitors to Wales, sturdy sceptics on arrival, who have returned convinced of the truth of the omen. That these “candles” are other than the ordinary ignis fatuus I do not suppose, and all allowance must be made for embellishments to establish coincidences. The “corpse-candle” seems to invert the ordinary phenomenon. It is easy to imagine the luminous globule rising from a charnel-vault or recently-opened grave and slowly drifting along the village street to scare the belated wanderer or horrify the old lady who watches it from her casement, but that it should rise from some quiet home, travel at funeral pace to the graveyard, and there disappear is peculiar, to say the least, and if true is an instance of the characteristic perversity of the meteor.

That superstition has laid hold upon it I do not wonder. Its simulation of the friendly light so longed for by the wayfarer, its mocking dance before his eyes, its habit of leading him to danger and even death, its weird and unaccountable vagaries, might well lead the simple-minded to regard it, as they always seem to have done, as the visible manifestation of some malignant and infernal demon.

Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand, Vol. 30, 1897: pp. 87-91

Robert Coupland Harding was primarily a printer, journalist, and typographer. His real love was printing and type-faces, so it is a little strange to find him presenting a paper before a learned society about his uncanny experience, although will-o’-the-wisp stories were popular filler for newspapers and the amateur naturalist was accorded much more respect in the 19th century than he/she is today. Several things struck me about his account. First, the use of the now-obsolete term “meteor” for ignis fatuus. Several 18th-century dictionaries define will-o’-the-wisp thusly:

Will with a wisp, or Jack in a Lanthorn, a fiery Meteor, or Exhalation that appears in the Night, commonly haunting Church-yard, Marshy and Fenny Places, as being evaporated out of a fat soil; it also flies about Rivers, Hedges, &c. [1707]

And

Will with a Whisp [1755 Wisp], a fiery Meteor or Exhalation [etc. as above, 1707, with the addition:] and often in dark Nights misleads Travellers by their making towards it, not duly regarding their Way.

We have seen reports of the “Fiery Exhalations” of Wales before.

Second, equally curious is his aversion to “these horrible little bubbles,” which he suggests have some sort of consciousness. This seems at odds with his closely-observed, careful analysis of their appearance, the terrain, and theories of their composition.

Third, I have never heard of spook lights, which are usually globes, described as cylindrical, except for the Welsh variety of “corpse-candles” that are said to look like actual candles moving in the air unless the observers were actually describing floating flames as “candles.” Is there any connection between what Harding saw and that transparent “glass tube” seen in the Tower of London?

Fourth, was Chambers right that improved drainage and farming set the marsh lights to going out all over Europe?

Illumine me: chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.