Cheiro and the Czar

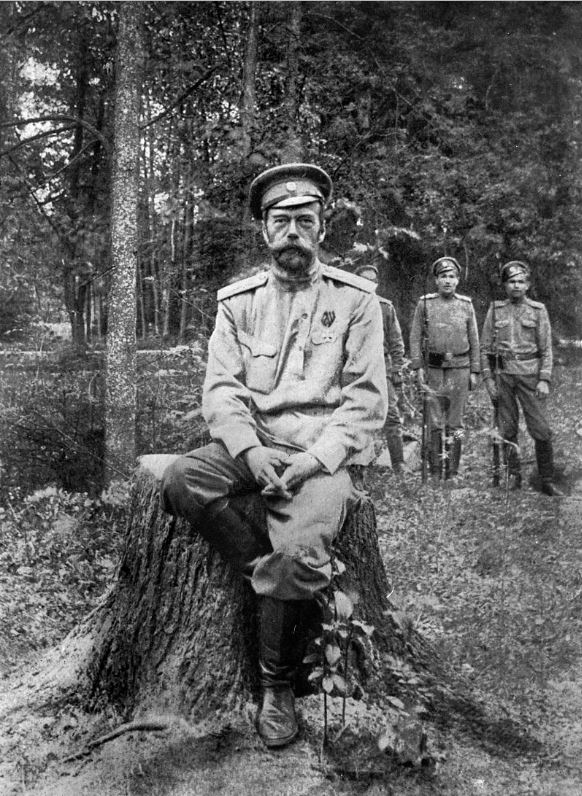

Cheiro and the Czar Ex-Czar Nicholas II after his abdication in March of 1917.

Today is the 100th anniversary of the murder of the Romanov family at Yekaterinburg, 17 July 1918.

Although today the Romanovs are viewed by many through rose-coloured lorgnettes enamelled by Faberge, the United States papers of the past were quite harsh in their stories of Russian ignorance and brutality, Imperial superstition and of Czar Nicholas’s weak character and inept leadership. Although Spiritualist journals analyzed horoscopes of the Czar (and other royals), but despite the hostility of the press and the outbreak of the Revolution, it is surprising to find that there were few people predicting the Romanov murders either before or after the fact. You’ll find a collection of a few, rather dubious visions in this post.

The society palmist “Cheiro,” whom we have met before in a story about his encounter with Mata Hari, claimed that he warned Czar Nicholas of the horrors to come a full decade before the Russian Revolution and that he even gave him a way to escape his unhappy fate.

In the course of his career Cheiro held the well-manicured hands of a very elite clientele, and seems to have pulled no punches when he saw doom in those hands. Cheiro tells the story of his encounters with Nicholas in his 1932 memoirs, which included anecdotes from his visit to Russia around 1907. The palmist had a reputation of being uncannily accurate; I leave it to you to judge whether he truly predicted the end of the Imperial family or perhaps embellished his prophecies after the fact.

Some few years ago a London paper mentioned that “when the Czar was in England, he frequently consulted the famous seer, ‘Cheiro,’ and it was from him he heard that war would be fatal to him and his immediate family; hence his famous Peace Rescript.”

I can now add a little more that may be interesting to my readers in this connection. I related many times in Press interviews how the late King Edward VII, when Prince of Wales, in his library at Marlborough House, got me from six o’clock until eight one evening, to work out for him the birth dates of quite a number of persons without giving me any clues to their positions in life.

About a year later, a gentleman called on me one afternoon and producing a sheet of paper covered with my own writing, asked me to explain my reasons for saying that “whoever the man is that these numbers and birth date represent, will be haunted all his life by the horrors of war and bloodshed; that he will do his utmost to prevent them, but his Destiny was so intimately associated with such things, that his name will be bound up with some of the most far-reaching and bloodiest wars in history, and that in the end, about 1917, he will lose all he loves most by sword or strife in one form or another, and he himself will meet a violent death.”

My visitor did not tell me he was the person the paper referred to, but he took copious notes of my explanations and at the end of the interview paid the usual fee for my time and left. A few weeks later a Russian lady called, and among other things told me that the Czar had called on me lately and that I had profoundly upset him by my predictions.

“You have made a peace convert of our Czar,” she said, “so I do not think we will find his name associated with war in any shape or form.”

In 1904, when I was in St. Petersburg on an important business matter, I again met this lady. She was dressed in deep mourning for her only son killed in the Russo-Japanese War, and I shall never forget how, in bidding good-bye, she said, “But there will never be another war in which Russia will be engaged, at least not as long as our Emperor lives.”

A few days later, while in St. Petersburg, I was asked to work out the figures for one of the most prominent Russian Ministers, Monsieur [Alexander] Isvolsky, and an intimate friend of the Czar. In this forecast for him of the following years I wrote: “During 1914-1917 you will be called upon to play a role in connection with another Russian war which will be ten times more important than the last. In this, the most terrible war that Russia has ever been engaged in, you will again play a very responsible part, but I do not think you will be fated to see the end of it. You, yourself, will lose everything by this coming war and will die in poverty in a strange land.”

A week later, I was taken out by this Minister to see the Czar’s Summer Palace at Peterhof. He first drove me through the wonderful gardens surrounding it. Below us lay the private yacht with steam up and ready at a moment’s notice if the Czar had reason to escape from the country.

“What a terrible way for the Czar to live,” I exclaimed.

“Yes,” His Excellency replied, ”but this is Russia. You did not notice perhaps that this car we have driven in has not an atom of wood in its structure, it is all steel and bomb-proof.”

Just then we passed the famous waterfall of the golden steps, sheets of crystal water flowing over wide steps of beaten gold. What a land of contrasts, I thought.

As we drove near the Palace, my friend the Minister said: “I will now tell you that I have brought you out to dine with the Czar to-night. I do not know if the Czarina will be present, but if she is, I want you to avoid all subjects touching on occultism. She may very likely recognize you, as she has all your books sent her from London; but remember, I shall depend on you to change the subject as quickly as possible should she talk about predictions, or her dread of the future, or anything of that kind. With the Czar, however, it is quite another matter; I have told him of your gloomy predictions for me, he has asked me to bring you, and after dinner he will probably take you with him into his private study.”

“But, Your Excellency,” I said, “how can I possibly dine with the Imperial Family like this–a blue serge suit will be impossible.”

“On the contrary,” he laughed, “it will be quite all right. We will dine in a private apartment with probably one servant to serve us. I am in a blue serge suit myself, and it would not surprise me if His Imperial Majesty, the Czar of All the Russias, will not be in blue serge also, as it is by his own request we are coming in this informal manner.”

At this moment the motor stopped at the door of the Palace, and an officer of the Imperial Guard met us. After passing through one long corridor after another, we were shown into a beautiful room that looked like a library. At first I thought we were alone, but no. There, seated in an easy chair by the window, was the Czar of All the Russias, looking for all the world like an ordinary English gentleman–and reading The Times, too, from London.

I stood still as if riveted to the door. I could not make a mistake–before me was decidedly the same man who had visited me in my consulting-rooms in London many years before. He came forward with his hand out. I bowed, but he took my hand all the same. We walked over to the window and looked out over the gardens and down to the beautiful yacht moored underneath. There was nothing worth recording in the conversation that followed; the three of us smoked Russian cigarettes, one after the other, and as the clock struck eight, a door opened and dinner was announced. At that moment the Czarina entered. She simply bowed to the Minister who was with me, then to me, and we went in to dinner.

His Excellency had been right. It was indeed a private dinner and without any ceremony whatever. Her Majesty wore a kind of semi-evening dress, but with no jewels, except one magnificent diamond at her throat. There was nothing extraordinary about the dinner; the zadcouskies [zakuski] were numberless, the sturgeon was excellent, but the rest was like what one would expect at any gentleman’s house.

I had no difficulty in avoiding questions on occultism from Her Majesty–she hardly spoke, in fact she did not seem to notice me. She appeared very distraught, spoke of Alexis a few times to the Czar, and the moment dinner was finished she bowed to us in a very stately way and left the room.

When we had finished our coffee and cigarettes, His Majesty said some words in Russian to the Minister–it was the only time I had heard Russian spoken all the evening, for the conversation had been entirely in English and French, and mostly in English.

As we left the dining-room His Excellency whispered, “Go with His Majesty, I will come back for you later.”

I did what I was told and soon found myself in a rather odd-shaped room alone with the Czar. This room was, I expect, his own private study, as it led into a very handsome bedroom which I could see through the door, and from it the Czar later came out with a large leather case in his hands. Taking a small key from the end of his chain, he opened the case, and to my amazement laid on the table by my side the identical sheet of paper with my own writing and numbers on it which I had jotted down in King Edward’s library, and had seen once again in my consulting-rooms in the hands of the man now sitting opposite to me.

The Czar saw my look of surprise. Pushing across the table at which we were seated a very large box of cigarettes–the box looked made of solid gold with the Imperial Arms of Russia set in jewels–he said slowly and impressively: “I showed you this paper once before. Do you remember?”

I gasped with astonishment. Yes, I did indeed remember. And I knew the words on the paper were the terrible words of impending fate.

“Do you recognize your writing?” he asked.

“Yes, Your Majesty,” I answered, “but may I ask how that paper came into your possession?”

“King Edward gave it to me, and you confirmed what it contained when I called on you in London some years ago, although you certainly did not know who your visitor was. Your written predictions to Isvolsky again bears out what is given on this sheet of paper. To-night there are two other lives I want you to work out.”

I gave the Czar my word of honour that I would not reveal what passed between us that evening in his study in the Summer Palace of Peterhof. Sufficient to say that he knew–that he was a fated monarch.

At his request, I worked out before his eyes the charts of two other lives he asked about; both showed the same thing, that 1917 was “overwhelmed by dark and sinister influences that pointed to ‘The End.'” I was amazed at the calm way in which he heard my conclusions; in the simplest way he said: “’Cheiro,’ it has given me the deepest pleasure to have this conversation with you. I admire the way you stand by the conclusions you have arrived at.”

He rose, we went out and joined Isvolsky on the terrace. Beneath us on the summer sea, the Imperial yacht lay like a painted toy, by my side stood His Imperial Majesty, the Czar of All the Russias, the Anointed Head of the Church and the “Little Father” of his people, and yet even then there were outward and visible signs that all was not right with the heart of Russia.

A short time later I was awakened one morning in my hotel to be told by a police officer that on that day from nine o’clock until midday, no one would be allowed to look out of any windows having a view on the Nevsky Prospect. His Majesty the Czar was about to pass to dedicate the church built over the spot where his predecessor had been assassinated.

Every window was closed and the slatted wooden shutters bolted. I could not resist the temptation when in the distance I heard the procession coming nearer and nearer. I crept across the floor on my hands and knees, to where one of the slats did not fit closely. What a sight it was–from that third-floor window. The Czar’s carriage surrounded by the Imperial Guard swept past rapidly, the long Nevsky was lined by troops so close together that they were shoulder to shoulder like two walls of armed men; but, was it possible to believe one’s eyes–each soldier had his rifle pointed at the windows of the houses along the route, with orders to fire if any person disobeyed the order and looked out–and yet we hear that “the Little Father was loved by his people.”

On another occasion, a few months later, when the first snow of winter made the streets almost impassable, I met a procession of some fifty men with a few women handcuffed together being driven to a station to be entrained for Siberia. They had been arrested at their work, some were in shirt-sleeves, some in their overalls, but just as they were, they were being marched through the streets with the thermometer at 18 degrees below zero.

As if it were a funeral that was passing, my droshky driver held his fur cap in his hand and made the Sign of the Cross–involuntarily I did the same.

Confessions: Memoirs of a Modern Seer, “Cheiro” (Count Louis Hamon) 1932: p. 62-66

As a footnote to his predictions for 1917, Cheiro added (in 1932) the following historical details:

1 March 12th, 1917, the Russian Revolution,

March 15th, 1917, Abdication of the Czar

July 16th, 1918, the Czar and Imperial Family massacred. [There is debate over whether the massacre began on the 16th and carried over to the 17th.]

The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood, built on the spot where Nicholas II’s grandfather, Czar Alexander II was assassinated, was finished–and I assume–dedicated in 1907, which gives us a probable date for Cheiro’s visit with the Czar and his predictions.

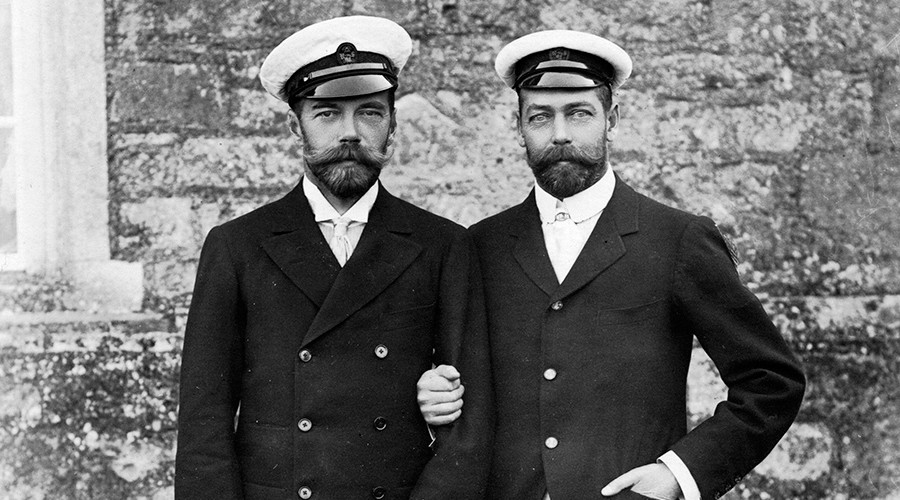

There are some areas of concern. First, Cheiro leads off with “a London paper” noting that “when the Czar was in England, he frequently consulted the famous seer, ‘Cheiro,'” which does not exactly square with his having read Nicholas’s chart first for the Prince of Wales. If Nicholas “frequently,” visited the palm-reader, one would think that Cherio, as a man who, for professional reasons, would need to cultivate an excellent memory, would not have been surprised to find his mystery client of a year later was the Czar. Nicholas’s photograph was frequently in the papers and he bore an uncanny resemblance to his cousin George, later King George V, so unless he had a damned good disguise, his incognito visit to the palm-reader, if he made it at all, sounds unlikely.

Cheiro and the Csar Csar Nicholas II and George, Prince of Wales, later King George V.

The “Peace Rescript” of 1898, led to the Hague Peace Conference of 1899. Cheiro would like us to believe that he was the inspiration:

It may be that the Czar was impressed with my prediction when he visited me in London in 1894, and endeavoured to alter his destiny by making the effort for peace which he did a few years later; it is often that the smallest things give rise to the greatest results. Confessions, p. 83

He also may have gotten his facts wrong when he claims that Nicholas hesitated about escaping with the Imperial family to England.

Can Fate be averted?…The unhappy Czar of Russia might be said to be the sport of malignant Fate. As all the world knows, he had the inspiration that led to the Hague Conference and certainly dreamt of world-wide Peace. Yet his country fell a prey to anarchy, while he himself was foredoomed to a violent end.

One may certainly say that Nicholas of Russia could have averted Fate. There was a time when he might have escaped from Russia; indeed the Empress implored him to get away to England, and a scheme was formed, but like a man in a dream, he could come to no decision until his abdication was followed by arrest and the final blood-red tragedy of Ekatrinberg. [Confessions, p. 109]

Nicholas himself seemed eager to flee with his family to an English exile. A rather reluctant offer of asylum was offered to the Imperial family, but was withdrawn as a politically inexpedient move–by King George V himself, say some historians. The ex-Empress was regarded as pro-German and there were also fears that the presence of the Romanovs in England would stir up violence from leftists and anarchists.

Despite this rejection, Nicholas and his family continued to believe that help would be coming–up to the very moment that it all ended in a hail of bullets in that tiny cellar room. There would be no averting of malignant Fate at the Hague; no private yacht, ready to steam to England. Instead, the doomed monarch and his family found themselves overwhelmed by those dark and sinister influences that pointed to ‘The End.’

Other prophecies of the end of the Imperial family? An exposé of Cheiro’s prophecies? chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead and on Twitter @hauntedohiobook. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.