A Walking Dead Man in Rotuma

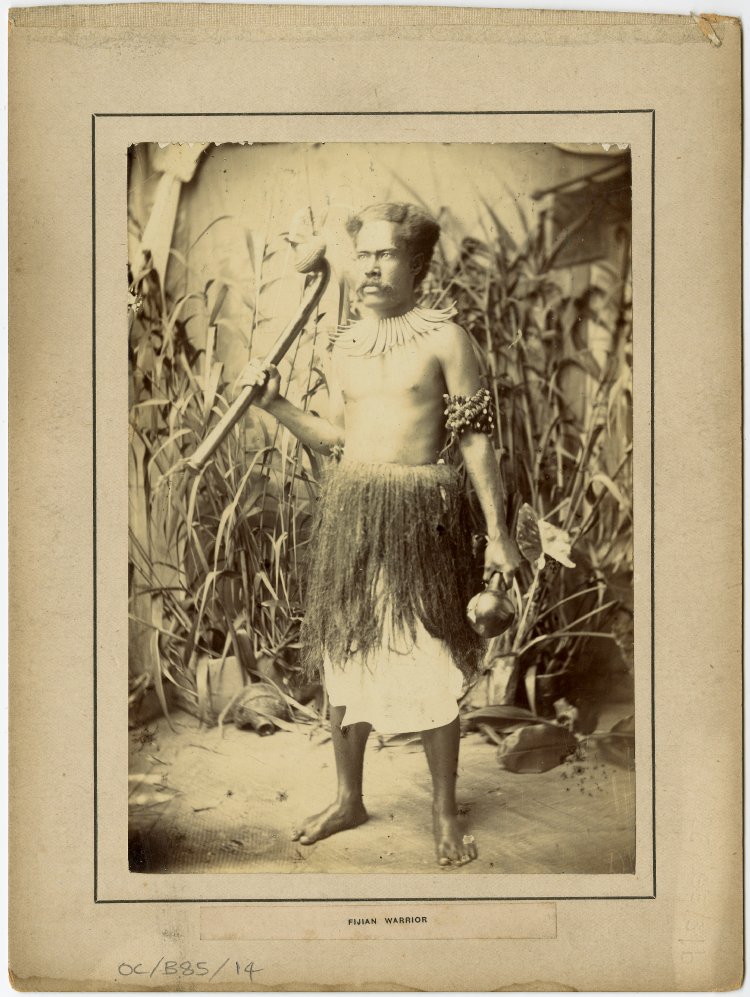

A warrior of Fiji, c. 1900 http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3081693&partId=1&searchText=fiji+warrior&images=true&page=1

There are times when you simply want to plunge into a good, old-fashioned book of ripping yarns about cannibal feasts and head-hunters. Such a book is The Western Pacific and New Guinea by Hugh Hastings Romilly, a British explorer and colonial administrator. Do not be deceived by the colorless title; there are anecdotes on pearl-diving and head-hunting, as well as a carefully observed description of a battle and the subsequent butchering, cooking, and eating of the victims.

There is also this story of a dead man walking from the tiny island of Rotuma:

The Governor had to put off his visit, and for five months I stayed in Rotumah without any news from the outer world, including the [measles] infected country of Fiji. In two months after my arrival there I went into my new house. It was very large and luxurious. Every evening Alipati used to come and have a talk and smoke with me. It was always open to any of my friends who cared to come. As I provided tobacco for them I seldom passed an evening by myself. The house was situated about 200 yards from Albert’s—Alipati’s— own house, and was just outside the limits of his town. A considerable clearing of four or five acres had been made in the bush to build it in. The short distance between the house and the village was of course very dark at night, as the path between them lay through a thick piece of bush. This sort of life went on with the exception of one break the whole time I was there. Two days before Christmas Day I was left all alone by my accustomed friends in the house, and spent the evening by myself. Allardyce and I made some remarks about it, but attached no importance to it of any sort. Next day I went to the other end of the island and did not come back till late. I had not seen Albert or any of his people during the day. In the evening I fully expected him up as a matter of course, but again no one made his appearance. I should have gone down myself to his house, as I thought that possibly a dance might be going on, which would account for no one making his appearance, but as it was raining heavily I did not go. I asked my native servants if anything was going on; they said there was no dance, and they did not know why Albert had not come. I saw by their manner that they knew something more, and I saw also that they were afraid to tell me what it was. I determined to see Albert early next day and find out everything from him. All that night we were annoyed by a harmless mad woman named Herena, who walked round and round the house crying ‘ Kimueli’ —’Kimueli.’ We thought nothing of it, as we were quite accustomed to her. Next day I went down early to Albert’s house. He was just going out to his work in the bush. I said, ‘Albert, why have you not been to see me for two nights?’

‘Me ‘fraid,’ said Albert, ‘dead man he walks.’

‘What dead man?’

‘Kimueli.’

Of course I laughed at him. It was an every-day occurrence for natives who had been out late at night in the bush, to come home saying they had seen ghosts. If I wished to send a message after sunset it was always necessary to engage three or four men to take it. Nothing would have induced any man to go by himself. The only man who was free from these fears was my interpreter, Friday. He was a native, but had lived all his life among white people. When Friday came down from his own village to my house that morning, he was evidently a good deal troubled in his mind. He said—

‘You remember that man Kimueli, Sir, that Tom killed.’

I said, ‘Yes, Albert says he is walking about.’

I expected Friday to laugh, but he looked very serious and said—

‘Every one in Motusa has seen him, Sir; the women are so frightened that they all sleep together in the big house.’

‘What does he do?’ said I. ‘Where has he been to? What men have seen him?’

Friday mentioned a number of houses into which Kimueli had gone. It appeared that his head was tied up with banana leaves and his face covered with blood. No one had heard him speak. This was unusual, as the ghosts I had heard the natives talk about on other occasions invariably made remarks on some common-place subject. The village was very much upset. For two nights this had happened, and several men and women had been terribly frightened. It was evident that all this was not imagination on the part of one man. I thought it possible that some madman was personating Kimueli, though it seemed almost impossible that any one could do so without being found out. I announced my determination to sit outside Albert’s house that night and watch for him. I also told Albert that I should bring a rifle and have a shot, if I saw the ghost. This I said for the benefit of any one who might be playing its part.

Poor Albert had to undergo a good deal of chaff for being afraid to walk two hundred yards through the bush to my house. He only said, ‘By-and-bye you see him too, then me laugh at you.’

The rest of the day was spent in the usual manner. Allardyce and I were to have dinner in Albert’s house; after that we were going to sit outside and watch for Kimueli. All the natives had come in very early that day from the bush. They were evidently unwilling to run the risk of being out after dark. Evening was now closing in, and they were all sitting in clusters outside their houses. It was, however, a bright moonlight night, and I could plainly recognise people at a considerable distance. Albert was getting very nervous, and only answered my questions in monosyllables.

For about two hours we sat there smoking and I was beginning to lose faith in Albert’s ghost, when all of a sudden he clutched my elbow and pointed with his finger. I looked in the direction pointed out by him, and he whispered

‘Kimueli.’

I certainly saw about a hundred yards off what appeared to be the ordinary figure of a native advancing. He had something tied round his head, as yet I could not see what. He was advancing straight towards us. We sat still and waited. The natives sitting in front of their doors got closer together and pointed at the advancing figure. All this time I was watching it most intently. A recollection of having seen that figure was forcing itself upon my mind more strongly every moment, and suddenly the exact scene, when I had gone with Gordon to visit the murdered man, came back on my mind with great vividness. There was the same man in front of me, his face covered with blood, and a dirty cloth over his head, kept in its place by banana leaves which were secured with fibre and cotton thread. There was the same man, and there was the bandage round his head, leaf for leaf, and tie for tie, identical with the picture already present in my mind. ‘By Jove it is Kimueli,’ I said to Allardyce in a whisper. By this time he had passed us, walking straight in the direction of the clump of bush in which my house was situated. We jumped up and gave chase, but he got to the edge of the bush before we reached him. Though only a few yards ahead of us, and a bright moonlight night, we here lost all trace of him. He had disappeared, and all that was left was a feeling of consternation and annoyance on my mind. We had to accept what we had seen; no explanation was possible. It was impossible to account for his appearance or disappearance. I went back to Albert’s house in a most perplexed frame of mind. The fact of its being Christmas day, the anniversary of Tom’s attack on Kimueli, made it still more remarkable.

I had myself only seen Kimueli two or three times in life, but still I remembered him perfectly, and the man or ghost, whichever it was who had just passed, exactly recalled his features. I had remembered too in a general way how Kimueli’s head had been bandaged with rags and banana leaves, but on the appearance of this figure it came back to me exactly, even to the position of the knots. I could not then, and do not now, believe it was in the power of any native to play the part so exactly. A native could and often does work himself up into a state of temporary madness, under the influence of which he might believe himself to be any one he chose, but the calm, quiet manner in which this figure had passed, was I believe entirely impossible for a native, acting such a part and before such an audience, to assume. Moreover Albert and every one else scouted the idea. They all knew Kimueli intimately, had seen him every day and could not be mistaken. Allardyce had never seen him before, but can bear witness to what he saw that night.

I went back to my house and tried to dismiss the matter from my mind, but with indifferent success. I could not get over his disappearance. We were so close behind him, that if it had been a man forcing his way through the thick undergrowth we must have heard and seen him. There was no path where he had disappeared.

I determined to watch again next night. Till two in the morning I sat up with Albert smoking. No Kimueli made his appearance. Albert said he would not be seen again, and during my stay on the island he certainly never was. A month after this event I went on board a schooner bound for Sydney; my health had suffered severely, and it was imperative for me to go to a cooler climate. I can offer no explanation for this story. Till my arrival in England I never mentioned it to anyone; at the request of my friends, however, I now consent to publish it.

I am not a believer in ghosts. I believe a natural explanation of the story to exist, but the reader, who has patiently followed me thus far, must find it for himself, as I am unable to supply one.

A True Story of the Western Pacific in 1879-80, Hugh Hastings Romilly 1882: pp 70-82

Earlier in the book, Romilly described in detail how Kimueli’s head had been bandaged with banana leaves and rags so he seems to have been able to authoritatively identify the ghost. There doesn’t seem to be much point to Kimueli’s return, speaking from a conventional ghost story sense where a murder victim wants justice or revenge. Kimueli was properly buried and his murderer was caught and convicted. Romilly frankly admits he has no explanation.

Other Pacific island ghosts? chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.