“Decede” A Stamp Story of the Great War

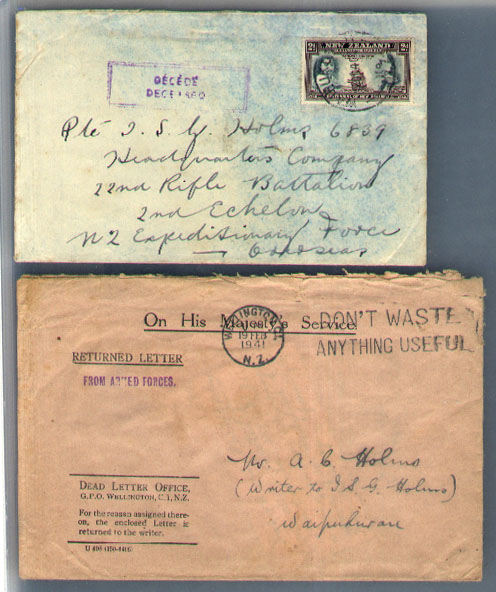

A Decede stamp from the Second World War. Source: http://www.completestamp.co.nz

The horrors of the First World War, reduced to stamps and statistics.

STAMP TELLS OF TRAGEDY

Black Bordered Poster Placed on Letters for Dead Soldiers.

Berne, Switzerland, Jan. 29. There is one small postage stamp, with a black border and a single word. “decede” (dead), which represents a greater tragedy than any battle in the present war. It is the stamp used by the international mail service, conducted by the Swiss government, between the prisoners of war of all nations and their families, on letters directed to soldiers who have fallen at the front or died in hospital.

A large table is piled high with these letters, each bearing the fatal stamp, “decede.” This is but one mail and each day’s mail piles the table again. They are to the families in England, Germany, France, Turkey, Austria, Japan—the entire range of fighting countries—for Switzerland has taken over the entire work of administering this mail service between families and their men at the front.

For a small country it is an enormous work that Switzerland has thus assumed, bearing the entire expense without a penny’s charge to anyone. Located right in the heart of the carnage, with the fighting nations on every side, Switzerland is peculiarly placed for effectively carrying on this humanitarian work. It is like the diplomatic work which the United State assumed for the different countries, but the magnitude of the work is probably greater owing to the vastness of these daily mails between all the fighting countries. And yet Switzerland does this work simply and without noise, and few know of the extent of the undertaking.

Accompanied by Secretary Breny of the post office department, who is in direct charge of the work, the Associate Press representative saw its many branches of activity in full operation. Even the big general post office of Switzerland was not adequate to carry on this international work, and the huge gymnasium was brought into service. Here the trapezes and flying rings have been looped to the side walls, along with rows of Indian clubs and dumb bells, giving a free open space for the enormous influx of soldier mail. Long trains on the mail vans are at the door, and some 30 to 50 wagon loads of this mail are handled daily.

“Here is something curious,” said one of the officials, turning to the German mail-bags. “you will notice they are made of paper—yes, paper mail-bags. Usually mail-bags are very stout, of leather or heavy canvas. But lately we have noticed the Germans are using paper for their bags. It means a big saving on their hemp, and the bags are strong and serviceable.” “Taking a knife, one of the paper mail-bags was cut, showing great resistance. It appeared to be a new quality of paper, with fibre almost like the mesh of cloth, but unmistakably paper.

“It is remarkable,’ said an onlooker, “how the Germans get up a serviceable substitute as soon as they run out of any article.” “Here is another curious and significant fact,” said the official in charge of the gymnasium mails. He help up a large card, a foot square, on which he had placed 21 samples of rope and twine.

“Those show the ingenious substitutes the Germans are now using for ordinary rope and twine,” said he.

The samples were from various mail bundles from Germany. They ranged in size from a small-size rope, about 1-8 inch thick to ordinary string. None of the 21 samples had any hemp. Most of the small strings and twines had a fine inner wire, to give tensile strength, wound with paper to give an outer finish and flexibility. The heavier ropes were of paper with strands wound together into a stout material. But the little inner wire seemed the basis of strength in these strange German substitutes for hemp rope and cord, required so enormously in ordinary business and commerce.

All about long lines of postal employees were at work sorting the soldier mail—letters, packages and money orders—going to various countries. Many poor people mail a loaf of bread daily to the son or father away at the front or in prison. One of the wrappings of a loaf of bread had broken open and disclosed that the sender had ingeniously inserted a copy of the Paris Matin inside the bread.

It was doubtless without malice, the officials said, by some poor mother who wanted their son to get a glimpse of the home paper. Most of the packages made one sad to see, they were so pathetic in their meagerness and yet so full of silent love. One was a small remnant of a Christmas tree, with some of the trinkets adhering. Others were packages neatly divided into small sections of chocolate, tobacco, soap and other needs and small luxuries of the men away from home.

But the most poignant branch of this busy bureau was the table heaped with letters and packages which could never be delivered, each bearing the stamp “decede.” One employe was binding these letters in packages of a hundred, and there were many of these hundreds, with the incoming vans adding to them constantly. When the letters are first received every effort is made to deliver them, but when the official record or other authoritative information shows the soldier is dead, the fatal black-bordered stamp “decede” goes on the latter and it is returned to the sender. And so this stamp carries into countless homes daily the news which is a tragedy to each one of these households—the first news, of the sending of the letter showed the family thought the son or father was still alive.

“There was a strange incident about one of those letters,” said the official. “The letter was sent by a mother in Germany to her son in France. Finding he was dead, the letter was returned to the mother, with the stamp ‘decede.’ But the mother, not understanding the French word ‘decede,’ thought it meant the name of the town to which her son had been transferred. And so she wrote him again, and this time all the children joined in the letter, and it was addressed to his name at ‘Decede, France.’ Of course there is no such place, and so again the letter went back with an explanation why it could not be delivered.

In other nearby rooms scores of male and female employes were at work on postal orders. It needed nice calculation in each case, making the exchange between French francs, German marks, English shillings, Russian robles, Italian lira, Austrian kroners, etc. These records kept by Mr. Breny showed France was sending about five times as much to Germany as was sent the other way, indicating more French prisoners than Germans or else more generosity. In October, for example, France sent 153,000 postal orders to French soldiers in Germany, totaling 1,581,000 francs. ($336,000), while Germany sent 34,000 orders to German soldiers in France, totaling 546,000 francs ($110,000). Russia is also sending an exceptionally large number of money orders to her soldiers in Austria, Hungary and Germany. Since the war began, over 35,000,000 francs ($7,000,000) has been transmitted from families to soldiers imprisoned in various countries.

Mr. Breny summed up the magnitude of this work in all classes of soldier mail as follows. “Each day the Swiss post office receives and forwards an average of 219,084 letters and postals, 16,912 small unregistered packages, 51,897 registered packages and 8,328 postal orders—this is the daily average on the special service of the soldier mail.

And yet Switzerland, a small and not rich country, is doing this work without charge and doing it gladly; its state railways carry all this mail free of charge; all postage stamps and duties are waived; hundreds of extra postal employes are engaged in the administration and expenditures of 20,000,000 francs ($4,000,000) of various kinds are waived—that is the way a small country is obeying a large impulse to do its share in the better part of the war’s work.

Grand Forks [ND] Daily Herald 30 January 1916: p. 9

Understand that I speak as a person of Swiss blood. I have a cousin who retired from a lifetime with the post office in the Canton of Bern. I recognize the bureaucratic precision; the statistical pride in the quantities of packages sent–registered and unregistered–not to mention the postal orders. The fascination with the rate of exchange. And the interest in gluing 21 samples of rope to a card in the midst of war. Money orders, ingenious paper mail bags, inventive substitutes for twine, little pieces of wire: it is as if focusing on the minutiae could reduce a world in flames to something more easily manageable–to a letter stamped “Decede,” and, with quiet Swiss efficiency, returned to sender.

Unfortunately I was not able to find an illustration of the Swiss Decede stamp online and used a much later image which is not the same. If anyone has a proper image they would care to share, please send to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.