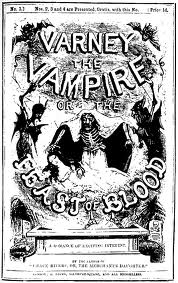

For the Blood is the Life or The Feast of Blood

During the last three decades, a vogue for vampire fantasy has spawned a dark culture where people identify themselves as vampires and drink blood. Yet there has always been a curious belief in the efficacy of blood-drinking, not as a lifestyle, but as cure or charm against vampires, as a specific for disease, or as a tonic.

First, there are treatments for vampirism itself. Presumably on the “hair-of-the-bat-that-bit-you” principle, remedies against vampires almost always involve ingesting some part of the creature, whether mixing the ashes of the heart or entrails with water or drinking the vampire’s own blood, perhaps baked into a revolting loaf:

In a French work, published nearly a century and a half ago, is an account of the Upiers or Vampyres, which infested Poland and Russia. “They appear,” says the author, “from mid-day to midnight, and suck the blood of men and beasts in such abundance, that it often issues again out of their mouth, nose and ears; and the corpse sometimes is found swimming in the blood with which its cere-cloth is filled. This Redivive or Upier (or some demon in his form) rises from the tomb, goes by night to hug and squeeze violently his relations or friends, and sucks their blood, so as to weaken and exhaust them, and at length occasion their death. This persecution is not confined to a single person, but extends throughout the family, unless it is arrested by cutting of the head, or opening the heart of the Upier, which they find in this cere-cloth, soft, flexible, tumid, and ruddy, although long ago dead. A large quantity of blood commonly flows from the body, which some mix up with flour and make bread of it; and this bread, when eaten, is found to preserve them from the vexation of the spectre.” It is singular, however, that thought the Vampyre himself might thus be rendered edible, he was imagined to communicate an infectious quality to whatever he fed on: so that, if any one were unlucky enough to eat the flesh of cattle which had been sucked, he would, after death, be sure of becoming a member of the blood-sucking fraternity. The Bell’s New Weekly Messenger [London] 30 April 1837

One would have thought that garlic bread would have been more appropriate and more palatable.

As a side note to blood remedies, vampires were also believed to be behind the dreaded lung disease consumption, now known as tuberculosis. There was no cure until the advent of antibiotics, but families often tried a dreadful, desperate remedy as seen in this story.

A STRANGE SUPERSTITION

The family of Philip Salladay came from Switzerland, bought and settled on a lot in the French Grant soon after the opening of the country for settlement. Hereditary consumption developed itself in the family sometime after their location in Scioto County. The head of the family and the oldest son [Samuel] had died of it, and others began to manifest symptoms, when an attempt was made to arrest the progress of the disease by a process which has been practiced in numerous instances, but without success.

Then the surviving members of the family resolved to resort to the strange “cure,” to disinter one of the victims, disembowel him and burn his entrails in a fire prepared for the purpose, in the presence of the survivors. This was accordingly done in the winter of 1816-17, in the presence not only of the living members of the Salladay family but of many spectators who lived in the neighborhood. Maj. Amos Wheeler, of Wheelersburg, was employed to disembowel the sacrificial victim (Samuel Salladay) and commit his entrails to the flames. [Another account says that Major Wheeler cut Samuel open and took out his heart, liver and lungs.]

But like other superstitious notions with regard to curing diseases, it proved of no avail. The other members of the family continued to die off until the last one was gone, except George.

SOURCES: Historical Collections of Ohio In Two Volumes, Vol. II, Henry Howe, (Cincinnati, OH: C.J. Krehbiel, 1902) p. 568 and A standard history of the Hanging Rock iron region of Ohio: an Authentic Narrative of the Past, with an Extended Survey of the Industrial and Commercial Development, Volume 1, edited by Eugene B. Willard, Daniel Webster Williams, George Ott Newman, Charles Boardman Taylor (The Lewis Publishing Company, 1916) pp. 44 & 71-72

This is the first time I have seen this practice mentioned in Ohio, although it was well-known in New England, particularly in Rhode Island. In New England, consumption, which was then almost invariably a killer, was called the “White Death” and victims were believed to come back as vampires to feed on the remaining family members. The only “remedy” was to dig up the dead person, take out his or her heart and burn it, and feed the ashes to the sick. In the Salladay’s case, the remaining relatives did not ingest the ashes. It seems to pile horror on horror to first disinter the decaying body of a loved one, go through the entire vile ritual, only to see more loved ones sicken, wither, and die.

You can find more information about this practice in the gruesome, but comprehensive Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires, Michael E. Bell.

But back to blood….

Next we have blood as a specific for otherwise incurable diseases. A “female vampire” in the 1860s was certain that the blood of an executed criminal would heal her heart. This strays over into the territory of hanged men’s hands being used to treat boils and hemorrhoids and a strand of gallow’s rope carried for health and luck.

A FEMALE VAMPIRE

There is a young married woman in St. Louis, a native of the Canton of Berne, Switzerland, who is afflicted with a disease which she calls “a dancing of the heart,” [perhaps some sort of Arrhythmia?] and which the physicians pronounce incurable. The lady with the “dancing heart” firmly believes that she can be cured by drinking a few drops of the blood of man who has been executed. Her name is Elizabeth Mund, and she is twenty-three years of age, and has been the mother of three children, none of whom survive. She has made numerous applications at the jail to inquire when there would be an execution, and as there has been no case of capital punishment at that institution for several months, her desire for human blood has not been gratified. She heard that John Abshire, sentenced by court martial to be hung by the neck, was to be executed in the jail yard on the 18th, as it was state in the papers. The execution of the sentence, however, was suspended, and on being informed that the man was not to be hung, Mrs. Mund appeared to be greatly disappointed and chagrined. Captain Bishop cheered her drooping spirits however, by telling her that on the 15th April a man would be hung by the neck until he was “dead, dead, dead,” and that she might then appear and obtain a dose of the blood of Valentine Hansen, the murderer, provided Governor Hall did not pardon or respite the criminal, and the physician would allow her to extract the curative fluid. With this pleasuring assurance Mrs. Mund took her departure, greatly consoled. This is a curious case of modern superstition. Augusta [GA] Chronicle 7 April 1865: p. 1

And the sequel:

Execution—A Female Vampire

Valentine Hanson was hung at St. Louis on the 15th for the murder of John Eng. He protested his innocence to the end, and was so overcome by fear and weakness that he had to be lifted on the scaffold. The parting with his wife in jail, who assured him that she believed him innocent, was very affecting. [Said wife grieved for all of eight days before she remarried.]

A notorious female vampire named Elisabeth Mund begged of Hanson’s wife and the jailer for a dose of the murderer’s blood which she considered a specific for her disease—a “dancing of the heart” as she termed it. Mrs. H. scorned the blood-sucker, and quite [illegible] of words allowed. The vampire took her place with the crowd in the street, still insisting that a drink of the blood of a man hanged by the neck would cure her of the heart disease, and she waited and watched with the hope that her strange desire might be gratified. Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 25 April 1864: p. 1

She was just a ghoul who couldn’t say no…

Finally, we find blood as a tonic. The human vampire in this bizarre story claimed to be a connoisseur of blood as he extolled the benefits of blood-drinking.

FOND OF HUMAN BLOOD

Morbid Taste of a German Tailor

Biting His Wife’s Arm

How the Sanguineous Fluid Brightens Him Up and

Makes Him Feel Fresh.

[New York Mercury.]

Ludwig Helreifel, a German tailor, living in Avenue B, between Second and Third streets, has acquired from his neighbors the singular name of “Blood Sucker.” He not only indulges in animal blood, as a tonic beverage, but expresses a preference for human blood, whenever he can get it.

This Singular Appetite

Was made by domestic troubles, which ended in a permanent separation between Helreifel and his wife; she, on her part, charging him with a dangerous inclination to gratify his unnatural thirst for blood at her expense. Habitual cruelty was, however, the legal plea. Curious to know how much truth there was in the rumors and stories told of Helreifel’s blood-thirsty inclinations, a Mercury reporter sought him out, in order to get from the man himself the truth, if any. Helreifel is a diminutive, swarthy man. His head is very large, and covered with a shock of bristly, black hair that makes his head appear out of all proportion to the body. Hair seems to grow everywhere upon the man; even upon the tip of his nose there is a considerable tuft of hair. He is no prepossessing man in appearance and this probably has something to do with prejudicing many against him. When asked by the reporter if it was true that he habitually drank human blood he answered by asking if the reporter was acquainted with his former wife, Margueretha. On being assured that there was no such acquaintance, he then readily and freely

Told His Story.

“Yes, it is true that I drink blood,” said Helreifel, “and it is good for me. It is a good medicine. It makes me strong. The Germans eat blood sausages, and they all say it is good. But when I drink mine they say it is bad, and they call me Bloodsucker. Now, what is the difference whether I take the blood before it is made into sausages or afterwards?…

“But didn’t you sometimes bite [your wife’s] arms?”

“Well, yes; I did bite her sometimes, but it was not for the blood, although the blood from a person is better than that from an animal. It is just as much better as good wine is better than some common wine. If you try it once you would see the difference. Human blood is richer, and it has a fine flavor.”

When questioned as to how he came to acquire such a singular appetite, Helreifel said it began in childhood. He was a very small delicate child, and, being the last survivor of six, his parents spared no trouble or expense to raise him. In Germany the poorer classes eat very little meat, while the children get almost none at all. But in Helreifel’s case the doctor pronounced it poverty of the blood, and ordered a solid meat diet for the child. Even this did not have the effect desired, and raw meat, and finally blood still warm from the animal was given to him. Every morning his mother would take him to a butcher’s where for four pfennigs, German money, a good drink of warm blood was obtained, the mother herself first tasting the blood to see if it was fresh and pure, or, as Helreifel expressed it, “not humbugged.”

In this way he soon acquired an appetite for fresh blood. A cut, or some similar accident, when a boy at school, first gave him a taste of human blood. Perceiving at once a difference, and that human blood was superior to animal, Helreifel acquired an actual appetite, a craving for the former. One reason for this preference was, he thought, because human blood was very difficult to obtain.

At parting Helreifel warned the reporter against heeding the slanders of his neighbors. “I like blood because it is good,” he said, “but these foolish women think I am like that bat which sucks the blood from people’s feet at night until they are dead. I am not like that, and they tell lies about me when they call me Bloodsucker. I believe some of them think I would suck the blood from my own veins if I could not get it from another person, and that is humbug. I like a glass of human blood just as people like a glass of good wine. It brings a good feeling and makes me fresh and healthy; a good wine does the same thing; there is no difference.” Fort Wayne [IN] Weekly Sentinel 9 July 1897: p. 1

NOTE: This is alleged to have been printed in the New York Mercury, which ceased publication in 1896. If this not just a journalistic hoax, it may simply be a late reprinting.

Now, anyone for a Bloody Mary? For medicinal purposes only, mind.

You’ll find a post on vampire superstition in Pennsylvania at Mrs Daffodil Digresses. I’ve written more about drinking blood as a tonic here, and about a blood-drinking cult here.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.