Pulling the Plug From the Bucket: The Self-hanging Gallows

Dr Beachcombing recently began a new series on non-standard methods of execution, starting with The Hanging Bed and Execution by Cannon. Let’s contribute to the grisly canon with this new and improved self-hanging gallows.

AGAIN THE GALLOWS FOR THE MURDERER

Death Penalty for the Punishment of Slayers of Men Will Be Revived in This State One Week From Tomorrow.

SCAFFOLD BEING ERECTED AT THE PEN

Grewsome Task of the Warden to Prepare to Carry Out of the New Law—How the Condemned Is Made to Hang Himself.

One week from tomorrow the death penalty as a punishment for capital crimes will be revived in Colorado.

It will then be ninety days since the legislature adjourned, the time limit when all bills unacted upon by the governor become laws.

This law was among the measures that were neither signed nor vetoed.

For the past month Warden E.H. Martin of the penitentiary has been busily at work getting the execution house at Canon City in readiness for victims who will be sentenced under the new law.

It was completed yesterday, and the plans of this grewsome department of the prison and the hanging apparatus will be forwarded to Denver next week for the approval of the board of charities and corrections.

As the general idea of the machine is the same as was in force before capital punishment was abolished it will likely be passed upon favorably. The system of execution is regarded as among the most humane in existence. Colorado, however, is the only state that has it or ever did use it, though it has attracted general attention all over the country. The apparatus was invented by a convict in the penitentiary ten years ago.

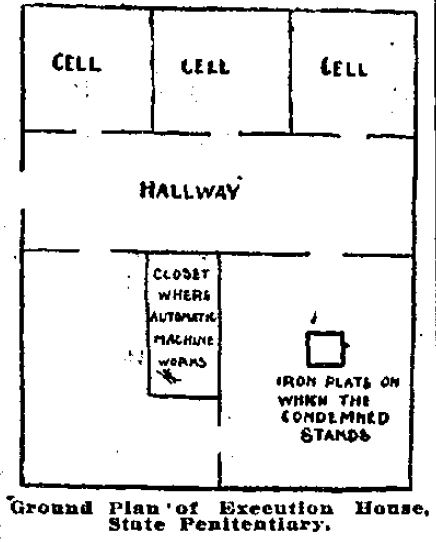

There were twelve persons executed by it, and not in any single instance was there a semblance of a failure. Death in every case was apparently instantaneous. This is the only hanging machine where the victim hangs himself. The arrangement is automatic, though some electrical devices have been added to the new machine. The proposition is a simple one. The execution house is a stone building 30 by 28 feet, just inside the main wall of the prison. It contains three condemned cells, about eight feet square, and across a narrow hallway is the execution chamber.

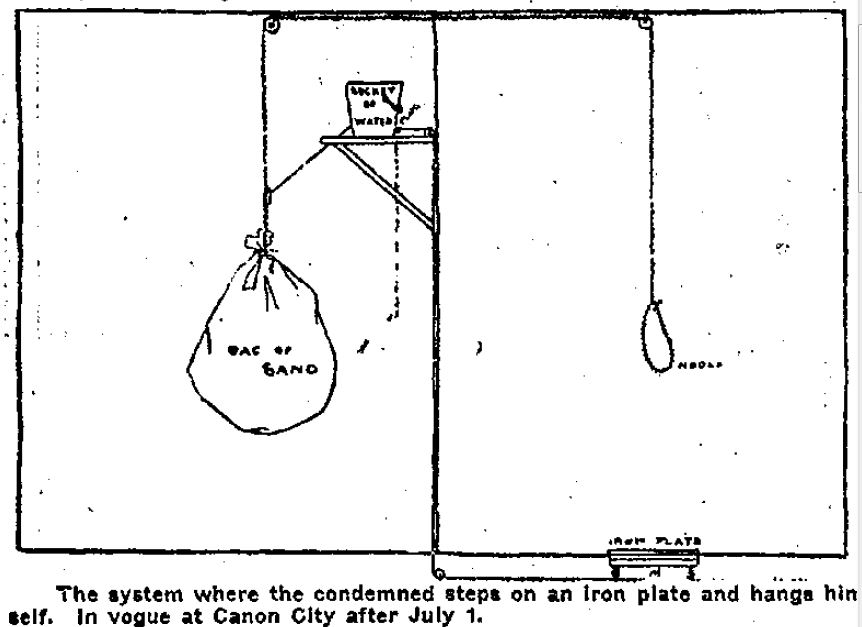

There is an iron plate in the center of the floor of this room, and after the condemned has the noose adjusted to his neck and the black cap placed over his head and face he is ordered to step forward a few paces upon this plate, which is a part of the hanging machine. The weight of the man causes the plate to drop about an inch. This closes the circuit of a current connecting with a bucket of water which stands on a shelf in a closet in an adjoining room. By a magnet arrangement a plug in the bottom of the bucket is pulled. Then the water begins to flow out, and as soon as the vessel is empty an automatic connection releases a catch holding a bag of sand on the other end of the rope containing the noose. The sand being heavier than the man, falls, causing the body at the other extremity of the rope to be jerked off the floor to a height of about three feet. The sand bag is in the room containing the closet where the bucket is kept, and the rope from the noose reaches that room over a pulley and through a hole in the wall.

The condemned does not see any of the details of the execution when he entered the death chamber. The iron plate in the floor and the noose around his neck are the only parts that he feels beforehand. He does not hear the dropping of the water or the working of any of the mechanism.

The instant the man is jerked off his feet and suspended at the end of the rope his neck is broken. The time intervening between the pulling of the plug in the bucket and the falling of the sand is usually about a minute. The suspense to the prisoner, however is not regarded as any more cruel than that experienced by a man in the electrical chair or on the scaffold while he awaits the fatal current or the springing of the trap.

Prior to 1889 capital punishment, under the law, was inflicted by the sheriff of the county seat where the trial was had. By an act approved April 19, 1889, it was ordered that all official executions should be had at the state penitentiary.

By an act approved March 29, 1897, capital punishment was abolished in this state.

The new law reviving it prescribes the method of execution in only that the “prisoner shall be hung by the neck until he is dead.”

The selection of a system of hanging is left entirely to the warden of the penitentiary. The executions are to be secret and are to take place within ninety days of the sentence.

Denver [CO] Post 23 June 1901: p. 10

Well, that is all very clear and business-like and humane. I was curious about why Colorado had a change of heart on capital punishment. Here is some background:

After capital punishment was abolished in the state in 1897, the debate continued. Governor Thomas and Charles Stonaker, Secretary of the State Board of Pardons were “shocked” in January 1900 by the news of the lynching in Canon City of Thomas Reynolds, a convict who killed a guard as he escaped the Colorado state penitentiary.

Stonaker said “If lynching was ever justifiable, it was in this case, but I cannot put myself in the position of indorsing it. The affair will have no effect on the law. Capital punishment will never be restored. The people have outgrown it. It was useless. It was not a deterrent of crime. It is merely an end of the criminal.” The Denver [CO] Rocky Mountain News 27 January 1900: p. 8

Secretary Stonaker was too sanguine. A series of high-profile lynchings in (and out of) the state renewed the call for the death penalty. Here is a sample:

“The law abolishing capital punishment in Colorado continues to bear its natural and expected fruit. It is at the same time an encouragement to murder and a provocative of riot and mob frenzy…Wherever the abolition of capital punishment has been tried, in the United States and in foreign countries it has been found to be a mistake and the experiment has been abandoned after a fair trial. These facts were known in Colorado at the time our law was passed but the theorists and sentimentalists attach little importance to the experience of other people.

The present piece of legislative foolishness may be left on the statue books until every town in the state shall have had lynchings as in Pueblo, Canon City, and others have had, but in the end the punishment of death for murder will be restored, for it is the only punishment appropriate to a crime for which no reparation can be made and no compensatory punishment inflicted.” Colorado Springs [CO] Gazette 24 May 1900: p. 4

At the end of 1900 came an event that may have tipped the scales inexorably in favor of the death penalty. 11-year-old Louise Frost was found raped and murdered near Limon, Colorado on November 8, 1900. Her body had been hacked with a knife and her skull crushed in by a heavy foot. Several weeks filled with blood-hounds and speculation went by. A search of the town uncovered burnt clothing and a pair of shoes matching the prints at the murder scene. A teenaged boy named John Porter was arrested in Denver where he had fled with his father and brother. He had previously served time in a Kansas reform school for another assault on a young girl. Based on the shoes (which were Porter’s) and some blood-stained clothing the family had shipped to Kansas when they fled, the police were nearly certain they had the right man, but Porter stuck to his claim of innocence. After four days in the police “sweat box,” and a threat to implicate his father and brother, Porter confessed to the crime. Several contemporary news articles said that the police delayed putting him on the train to Lincoln County. They wanted to be absolutely sure of his guilt before sending him back to Limon where they were confident he would be lynched.

At a meeting of citizens of Limon and Lincoln counties it was unanimously voted that Sheriff Freeman be urged to bring to this town at once John Porter, murderer of Louise Frost. The meeting guarantees that there will be no atrocities before or after the death of the murderer, and urges this action upon Sheriff Freeman as the only way to restore the law to its normal course.”

It was in consequence of these resolutions that the prisoner was taken to Limon by the officers of the law acting under authority of the state for the purpose of delivering the prisoner to the mob, and by those officers he was so delivered. These resolutions exhibit “lynch law” at its best.

The man was unquestionably guilty.

His crime was most heinous.

No one can say that John Porter deserved less than death.

And the absence of any provision in the law for capital punishment gave an irresistible impetus towards lynching.

That the resolutions were not honestly kept, that the prison was burned at the stake rather than hanged, is the natural outcome of the circumstances…

“At its best it is the honest effort of the people rising in their primitive power to supply the defect in the legislative decrees….

We have already gained the knowledge that public sentiment will insist upon the death penalty in certain cases of murder, no matter whether that penalty be written in the law or not, we have learned that the unorganized people of a farming community may resolve to act with all the decorum of a legal execution and their resolution be swept like dry leaves before a whirlwind in the passion of the moment. We have yet to learn to what lengths the mob may go in its unrestrained fury, if lynching becomes the regular and customary form of punishment for certain crimes.

But if the present lack in the criminal law of the state continues, we shall learn it. Colorado Springs [CO] Gazette 17 November 1900: p. 4

Porter was chained to a metal stake, drenched in coal oil, and burned alive. The fire was lit by Louise Frost’s father.

The horrific details were widely reported, in spite of strong letters from those who thought that such gruesome particulars did not belong in family newspapers. The ghastly nature of Porter’s murder seems to have been a strong factor in reinstating the death penalty in Colorado.

But back to our self-hanging gallows. Doubts voiced about capital punishment in the press often mention the degrading and traumatic effect on the executioner. This neat solution made those objections irrelevant, and laid the responsibility for his own execution squarely at the feet of the condemned man. One wonders if there was any provision made for prisoners who had moral or religious objections to suicide? The Colorado execution machine raised a nice theological point as stated in this notice of a similar device from a few years earlier:

An Alabama man has patented a scaffold on which to execute murderers. He has the spring so arranged that they can touch it themselves. This would save hangers from unpleasant surprises, but then there is a moral obstacle to the success of the invention. Many candidates for hanging claim to be prepared for admission to the home of the best, and should they spring the trap which hangs them they would be guilty of taking their own lives, and according to popular belief, be unfitted to enter the pearly gates. Fresno [CA] Republican Weekly 11 March 1887: p. 2

What does canon law say on the subject? May a man, subject to a legally sanctioned sentence of death, collude in his own execution? Thoughts to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

I’ve covered other aspects of executions in this post on hangmen’s ropes, on a death-mask execution device, four novel execution methods, and the Swedish Cone of Death.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com.