The Death of the Queen of Bohemia

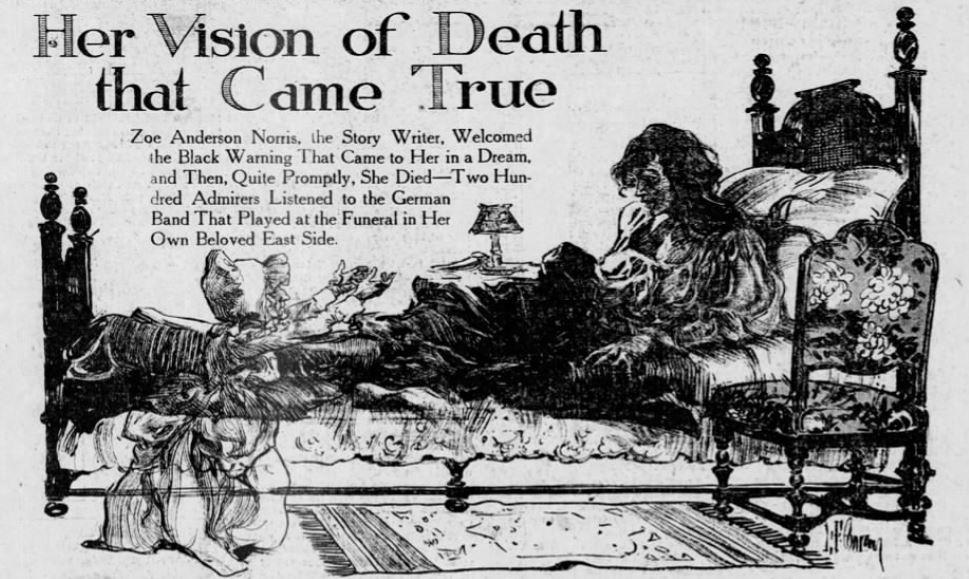

The Death of the Queen of Bohemia Death is predicted by her mother’s ghost for Zoe Anderson Norris, “The Queen of Bohemia.”

On the East Side of New York there once lived a Queen—journalist, author and philanthropist, Zoe Anderson Norris—affectionately known as the Queen of Bohemia. To the folks back in Kentucky, where she was born or in Wichita, where she had lived, the title suggested a shockingly disreputable life-style, compounded of smoking, corset-less Reform Dress, and late-night chafing-dish suppers with anarchists. The strange circumstances of her death only reinforced her image as a woman who cared nothing for convention.

ZOE ANDERSON NORRIS DEAD; SHE PREDICTED OWN FUNERAL

ONCE RESIDED IN WICHITA AND WELL KNOWN HERE

CALLED “QUEEN OF BOHEMIA”

PUBLISHED THE “EAST-SIDE” MAGAZINE IN NEW YORK CITY.

Only a Few Days Ago Mrs. Norris Wrote: “I Am Going to Take the Journey, Very, Very Soon.”

New York, Feb, 14. “I am going,” Zoe Anderson Norris wrote in the little magazine “East-Side,” or Zoe’s magazine, published under the date of February 12, “to take the journey to the undiscovered country very, very soon.”

The ink was hardly dry upon the pages of the magazine which was placed on sale two days ago, when word came last night from the People’s Hospital that Zoe Anderson Norris, the “Queen of Bohemia,” was dead; that she died as she had dreamed and predicted very, very soon.

Mrs. Norris was Miss Zoe Anderson and resided for several years in Wichita, Kan, She was born 47 years ago at Harrodsburg, Ky. She was married to S. W. Norris by whom she had one daughter. [also a son, Robert] Mr. Norris died several years ago.

She Was Loved by Many.

On the East Side where she lived Zoe Anderson Norris was beloved by many whose names are known in the social and literary registers of the city and by hundreds whose condition in life never led them beyond the narrow little Ghetto world.

Mrs. Norris had been contributor to magazines, she had done active newspaper work and five years ago began the publication of the little magazine in which in intimate fashion she told of her approaching death. She was best known of recent years by writers and newspaper people generally as the founder and spirit of the Ragged Edge Club.

Left Funeral Suggestions.

In her valedictory she requested that here funeral follow the East Side custom. It read:

“And I should like a lovely East Side funeral with the little Dutch band that plays every morning in my court leading it and the Ragged Edgers following on foot.”

HER FIRST LITERARY WORK IN WICHITA 15 YEARS AGO

Mrs. Zoe Anderson Norris Has Many Friends Among the Older Citizens of This City.

Zoe Anderson Norris began her literary work in Wichita fifteen years ago. She resided at Third and Market Streets then with her son Robert Norris and daughter Clarence Norris. Robert Norris now resides in Kansas City where he is employed by the Missouri Pacific. The daughter Clarence resides in the East and is married.

Mrs. Norris’s first literary contributions were to Wichita newspapers. Her style was breezy and different. This attracted the attention of magazine publishers who were soon purchasing her output. Although born and reared in Harrodsburg, Ky., by the time Zoe Anderson Norris left Wichita she was a typical Kansan. She was closely related to Senator Thompson of Harrodsburg.

Resided Here 10 Years.

She made many friends in Wichita during her ten year residence. They encouraged her to continue writing. After a separation from her husband she went to New York, plunged into the highly colored life of the East Side and soon became famous in Bohemia. Her charitable work in that district drew her a large following and she became “Zoe, Queen of Bohemia.”

“I had met her and heard much of her,” said La Touche Hancock, a visiting newspaperman and lecturer in Wichita today. “I’m very sorry to hear of her death. There’s no doubt that she was unusual. All over the East Side she was well known and much thought of. Her kindness and open purse were the striking features of that district.

Loved New York’s East Side.

“I visited her once. She received me in a jumbled-up sitting room, plain dress and over a cup of coffee we discussed literary conditions. She loved the East Side I know. You can feel sure that this darkened portion of New York lost one of its cheeriest rays when Zoe Anderson Norris died.

For two years she had been issuing the East-Side Magazine. It is an unusual publication written in her most fanciful style. The most recent number of the magazine published February 12 contained a prediction of her death. Her article is reproduced on this page today…

The Wichita [KS] Beacon 14 February 1914: p. 1

Norris’s death is one of those rare moments where a prediction sees print before its fulfillment. Here is what she published just two days before she died.

Zoe Anderson Norris’s

“DREAM OF DEATH”

The following article from Mrs. Zoe Anderson Norris’s East-Side Magazine, published February 12, is the one in which she wrote of her “Dream of Death.” The entire article follows:

Let me beg of you, Children, to be very good this year. I am going to be very, very good.

I’ll tell you why presently.

My beloved Kentucky Colonel used to say that this world was an Opera Bouffe with a Great Deity managing it and laughing at us, and it seemed so in his case. He was gaily spending his third fortune when he fell dead in the street.

Three weeks before, I sat with him in the Palm room at the Waldorf.

“I dreamed you were dead,” I told him.

This to let you know the strangeness of my dreams.

Take the case of that District Attorney Crouch.

The Deity permitted him to live a life of lies to the limit. Then, instead of striking him down at home so that the secret might be kept from the world, he felled him in the place of his iniquity, and his little whispering secret became a cry which resounded throughout the country, and, let us hope, frightened some who have their secrets so hidden into lives of uprightness, honesty and truth. Let us hope so, but don’t let’s count on it too much. It is man’s nature, they say, to lie and deceive. What if it were woman’s nature? What if women kept their affinities within a stone’s throw of their homes’? But then they may when they get to be District-Attorneys. Who knows?

I think that there will come a day when a husband must respect his wife’s honor in the same way that she respects his; but we won’t live to see it, Little One. At least I won’t.

I am going to take the journey to the Undiscovered Country very, very soon, if there is anything in dreams; and if you knew the dreams of my life, you would say there is.

Do you remember how, in the July and August number, I said that the dead never come back?

Well, when you say such a thing positively, the Great Deity says to Himself, “I’ll show her just how little she knows.”

That is what happened to me.

But first, so that you may understand the dream, I must tell you of my family, how my father died, then one after another of them, two years apart, until five had died, always two years apart.

There was a long stretch of years without deaths, then four years ago a beloved sister died, and two years ago another.

Now I will tell you of my dream. I was sitting alone one night not long after I had published that audacious statement that the dead never come back, sat very lonely in the big chair under the lamp, pondering over the problem of life and wondering, as I often do, what was the use of it all anyhow, and then I went to bed and slept. Along toward dawn I had a dream.

Again I sat alone, wondering, wondering. And then I thought there came swiftly down a long and dusky hall a little woman, a tiny little woman in black.

As she came down the hall, the doors swung open and shut for her in a mysterious way, as if blown by winds.

Finally she reached my bed and stood there. It was my mother, such a tiny little thing to have borne thirteen children.

She was hardly higher than the posts of my low bed as she stood there by me.

In my dream I put up my arms and clasped them about her. I felt the soft slazy silk of her black dress.

“Am I the next’?” I asked her and she said: “Yes.”

I screamed, and she put up her small hand and said: “Shhh! Shhh!”

My scream wakened me.

How glad I was that it was light for though I had put my arms around my little mother, I was afraid of her.

Her presence was so strongly with me that I think her spirit still stood there by my bed though I couldn’t see it, because of the light.

At any rate, the first thought that came to me as I lay there in the dawn, was that I didn’t care.

How tame life gets after you have lived it any length of time!

The same days, the same nights, the same seasons, the same heat, the same cold, the same grass, the same flowers, the same untruthfulness, the same insults from men, the same poisonous tongues of women, the same rich, the same poor, the same sunshine, the same rain!

I never blame the suicides for trying to find the other country. I blame only the idiotic laws of men which imprison them for trying to find it.

Maybe the skies are green there, just for a change, and the grasses are blue and the flowers are white, all white lilies.

There! That is my new name for it, The Land of the White Lilies, where it is summer all the year round and there is no discomfort and no chill.

Every time I have become ill and half delirious I have shivered with the cold and unhappiness of those desert plains of Kansas where I was forced to spend so many miserable years.

For when you are ill and delirious your mind goes back to the things of the past as learned men, upon their deathbeds, babble the baby talk they lisped at their mother’s knee.

I wish I had the unfaltering unquestioning faith in God that the Jews have. I must cultivate it.

Ameen Rahani says that in Tiberius the poverty of this race is ghastly, and yet their faith in God is perfect.

How beautiful that must be; to have a perfect faith in God!

My resentment at some of the terrors of my life has been so great at times that when I have been thrown upon my knees I have been filled with fury that there was nobody to go to but God.

I must pray very hard to be forgiven for that.

I have at these times had the greatest admiration for Job who had the grit and independence to say, “I will curse God and die.”

And I am afraid I would have done the same except for my fear of boils.

I must pray very hard to be forgiven for that.

I must go into the churches perhaps and sit through some sermons in order to get forgiveness.

Oh! Those deadly sermons! Those stupid inane and lifeless sermons, penances, that’s all. I really think they have done more to hurt religion than anything else, those pompous, “Thank God I am whiter than you” senselessness that send you to sleep, from sheer disgust and weariness.

I must try and forget too that I seem to have been a chief actor in this Opera Bouffe at which the Great Deity laughs.

Just as I have made my life worth living, have cut out a work for myself, have found myself, as it were, after long and most unhappy wandering, have made a little home for myself, have gathered friends about me many friends and warm whom I love and who love me. I must move on.

I must try and forget that and think instead how good it is to know that I am not to live to be old and helpless and feeble, to die in some sanitarium, helpless and ill-treated, as many women do; or sit on a curb and sell oranges all day long as the old women do here on the East Side.

If I have helped any woman to live her life with resignation and many letters from women tell me that I have or interested anybody in the poor for their benefit, I should be content to wend my way to the Land of the Lilies, and will make myself so in the time left me which may be next week or next month or next year.

And I consider myself fortunate to have been given time to prepare myself by this dream of my little mother, to forgive and forget, to love my neighbor, to bear no malice, to do as much good as possible, and if possible no harm, though never knowingly and with malice aforethought, as the lawyers say, have I done harm. And when I feel like crying a little at the thought of leaving my loved friends, I calm and console myself with the promise of the Holy Writ that in that far off unknown country there will be no marriages nor giving in marriage. I think I shall be killed by another automobile, I have such fear of the streets; but every night I’m not killed I plait my hair very neatly before I say my prayers and make myself pretty as possible for them to find me in the morning.

And I should like a lovely East Side funeral with the little Dutch band that plays every morning in my court leading it, and the Ragged Edgers [members of an association of magazine editors, which Norris founded.] following on foot, and black horses with fine long tails and manes and a covering like the waving fins of the Japanese goldfish, only black, of course, and all the other trimmings that go with a real and beautiful funeral here on the East Side where everything is so much more simple and near to nature than on the West.

And there are so many things I want to know about, my children, so many things I have wondered about all my life long, why some lead the lives of butterflies and others go barefooted, why the world is a fairy palace for some and a prison for others, why every sort of animal from man down must prey upon some other animal, the cat upon the canary, the dog upon the cat, the man upon the woman. And when I have found out the truth about all these things in the Land of the Lilies, my children, I will come back and tell you, because you see, after all, I was wrong and they can come back.

And you also, live God-fearingly and as if every moment may be your last, for you may take your journey to the Land of the Lilies, as soon as I, maybe sooner, “Will you be [home the] week before Christmas,” I said to a friend, “Will you be at my Christmas tree?” and she answered, “No I must go home for Christmas.”

She went home the day before and was buried on Friday.

Verily, I say to you, Beloved, keep your house in order in the same way that I shall do, and be very, very good and pray very, very hard; for we are all helpless in the hands of the Deity and not one of us knows the day or the hour.

Amen.

P.S. Lest mine enemies rejoice too gleefully, I wish to add that this may be one of those dreams that go by contraries, and I may yet have the pleasure of following them to the Happy Hunting Grounds.

The Wichita [KS] Beacon 14 February 1914: p. 14

We get a good flavor of Norris’s “fanciful” writing style in this elegiac piece. Also of her anger towards men who prey upon women and her hatred of convention, although she still retains orthodox notions of “Holy Writ,” forgiveness, and prayer.

Norris divorced her first husband in 1898—a relatively uncommon proceeding for the time. She married cartoonist and artist J.K. Bryans in 1902 and may have also divorced him, although I have not found the details.

Norris paints such an intriguing picture of the Land of White Lilies—where she was definitely not in Kansas any more—that we can see why she “didn’t care” whether she lived or died.

While the newspapers made much of Norris’s death-prophecy, I cannot find any reports that despite her assertion, “I was wrong and they can come back,” she ever returned from the Land of White Lilies to tell of the truths she had learned under those green skies.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.