War Toys of Germany

A clockwork torpedo boat made in Germany, c. 1912 1912 http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O88439/clockwork-toy-torpedo-gebruder-bing/

The season of Giving is almost at our throats, so naturally it is time to look at some painful historical toys from the Great War.

GERMAN CHILDREN GIVEN WAR TOYS FOR CHRISTMAS

Ruined Villages Depicted With Papier Mache and Toy Cannons in War Games.

Exploits of Submarines Are Featured for the Little ones to Enjoy

Paul Scott Mowrer.

Special Cable to the World-Herald and the Chicago Daily News.

With the French Armies, Nov. 11.

Germany is using the Christmas season to develop and harden the war spirit among its children. I have been permitted to visit a curious private museum where I have seen many holiday novelties in toys and games brought from Germany through Switzerland. That children in play should desire to emulate their elders is of course natural, but it was not without amazement that I discovered the latest and most popular German toys to be small ruined houses.

Last March the Kaiser’s armies in retiring from the Noyon salient, pillaged, burned and destroyed all human habitations with a thoroughness probably unparalleled in history. This Christmas the boys and girls of the fatherland in their nurseries may imitate the battlefield exploits of their fathers and older brothers. I examined a whole collection of inexpensive toy ruins made of some plaster composition and ingeniously colored to represent the debris of incendiarism, ranging from the models of shattered cottages to the pretension of smoke-blackened chateau.

All these astonishing miniature ruins are French in style and architecture, for naturally the tragedies at which the German children will soon be playing must all be supposed to take place beyond the German frontier. In addition to this novel invention of the Teutonic Christmas spirit are innumerable other playthings having to do with the war. I saw a savings bank labelled “Conscientious Bertha” shaped to imitate the famous 42-centimeter howitzer. [“Big Bertha”] I saw jigsaw puzzles and toy blocks showing battle scenes in all of which the Germans were bravely overwhelming their foes. New-born papier mache babies are represented as executing the military salute and singing “Die Wacht am Rhein” as they burst from colored egg shells. There are toy barbed wire entanglements, toy trenches, toy cannon and of course lead soldiers without number.

Become of the peculiarly German realism these last are worth looking at—sets of armed civilians entitled “franc-tireurs” (snipers) are supposed to represent the “crimes” of Belgium; German machine gun companies, German infantry charging, German hospital units with plenty of bloody bandages and patients, sets of fugitive French infantry and of French and English prisoners of war—finally, the most striking of all sets, dead and wounded Russians in every contortion of agony.

But German juvenile education in militarism goes beyond mere toys into the vast variety of “Kriegspiele” (war games) from simple games of maneuvering on a board to a whole series of “literary” games played with cards on the principle of “Authors.” Some decks of cards represent the German, Austrian and Turkish armies; others are devoted to the navy and the exploits of the submarines. The game which struck me as the most unusual consisted of fifty-two cards, each bearing the warlike utterance of some German soldier or statesman. Such maxims as dying for one’s country, or how victory is sure to crown the efforts of that peoples which can hold out the longest appeared. In short German “Blood and Iron” propaganda is being carried into every recreation of childhood.

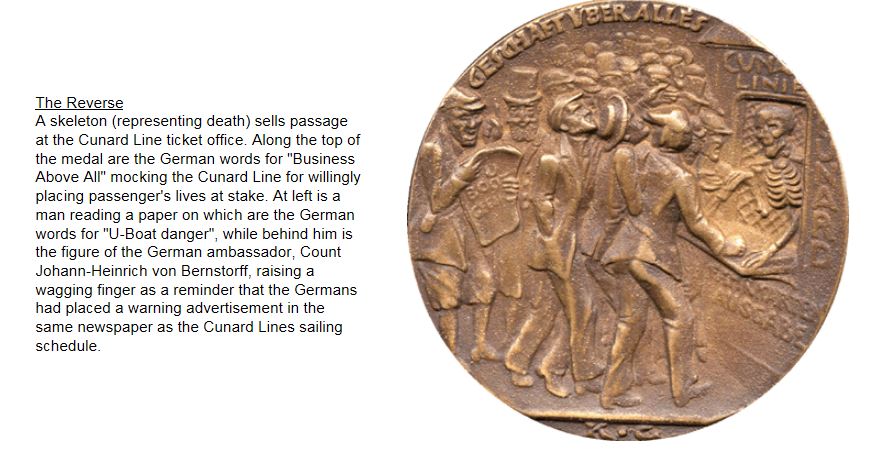

In other rooms of this museum I saw an original of the Lusitania medal with its ghastly design of the skeleton selling tickets to a group of passengers.

Lusitania medal with a skeleton ticket-seller. http://lusitaniamedal.com/medal.html

I also saw a sample of the ingenious little two-pronged needle-pointed hooks which Germans in America put into consignments of oats for the purpose of killing horses. But among all these barbaric horrors the toy ruins made the deepest impression. I have lived of late among too many real ruins. I know what they mean. Omaha [NE] World-Herald 14 December 1917: p. 11

When I came to the bit about the Lusitania medal, I thought that surely this was mere propaganda, but, as you can see from the illustration above, there really was such a medal. I also thought the dead Russian soldiers were an exaggeration, but when you see the toy in the illustration below, c. 1920 (possibly earlier) complete with explosions and dying soldiers, anything is apparently possible in the world of war toys.

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1222998/toy-bunker-set-o-m-hausser/

Here is another anti-war-toy article describing other ingeniously destructive toys.

AS TO WAR TOYS

“Child’s play” is a game to imitate the work of parents. The warrior’s child plays at making war. Since war is just now the work of a large part of the adult males of Europe it is not strange that war should be the play of European children. In France the children play in imitation trenches. In Germany they imitate the tactics of the drillmaster and, in at least one princely household we heard of, the princelings have been instructed by a lieutenant in the art of dropping flour bombs from toy Zeppelins on toy relief maps of Paris, London and Petrograd. In an English toy catalogue parents read that they may give their children guns which shoots “live shells” (warranted harmless), and forts which, with their defenders, can be blown up by pressing a button.

On the toy counters of our own city it is possible to find “the submarine game,” in which a torpedo shot at a vessel’s side jolted a spring and blew the toy ship to pieces. Amiable diversion for the infant mind!

All this means, however, that the generation of children now growing up will have learned to take the idea of war for granted and perhaps even make the destruction of life a game of innocent child’s play.

An eminent scientist gives it as his opinion that we shall never be able to eliminate war until we begin by eliminating it from the minds of young children.

War toys are hardly the way to begin. Boston Globe.

What an eminent scientist says is true, but as long as there are wars, it will be a matter of impossibility to eliminate war from the minds of the children. When men and women read about war and think about war and talk about war about half of the time it will be impossible to prevent the little folks hearing about it, and when they hear they are going to want to know more—they will want to know all.

But it would be just as well, perhaps, to leave off the war toys. The children will be just as well pleased with other kinds of toys and other kinds should be given them. There is no reason why they should be given something that is a constant reminder of war. Columbus [GA] Daily Enquirer 29 February 1916: p. 4

A fine sentiment, but, like the poor, war toys are always with us. And the American toy manufacturers, during a variety of wars, did not exactly cover themselves with glory. Take, for example, this extraordinarily offensive Christmas gift recommendation in the wake of the Spanish-American War:

Shooting Spaniards.

It cost Uncle Sam more than 45 cents apiece to shoot Spaniards during the recent war, but some clever fellow has invented a gun, which can be bought for that price, which shoots Spaniards and keeps a-shooting them. The small boy puts a cap in the gun, pulls the trigger, and as the explosion occurs a Spanish soldier, who has been concealed in the barrel, appears and throws up his hands. Then there is a new iron savings bank, in which an American cannon and a Spanish warship figure. As the warship stands, it covers up the slit for the money. The would-be depositor places a small ball in the mouth of the anon and pulls a spring. The ball is supposed to hit the Spanish ship and smash it into nothingness, but too often it fails to reach its mark, and one is apt to come to the conclusion that it is the cannon which is Spanish instead of the warship.

The war furnished a number of ideas for authors of games, and many of the game boxes which are offered for sale bear pictures of dead Spaniards and live Americans, exploding bombs, smoky battle fields and general excitement, with a nice, roomy corner generally reserved for the red, white and blue. Sioux City [IA] Journal 14 December 1898: p. 3

Other vintage war toys? I am preparing the flour bombs now. Chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Mrs Daffodil is also reporting on historic war toys here. Worth looking at just for the “Get Rid of Huns” maze puzzle illustration.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com.