The Veil Between

The Veil Between Veil between the living and the dead is rent.

For Father’s Day, a story of a father who rent the veil between the living and the dead.

The Veil Between.

Mary E. Mann

Author of “The Mating of a Dove,” etc.

Her husband had died suddenly in the third year of their marriage, and she had been left a young widow with their only child.

The husband had been dead a year— a year passed in close seclusion in her country home—when she went out on a bright morning of the early spring, taking her little daughter with her, to gather primroses in the plantation which bordered one extremity of the park around her house.

She had remembered when she arose in the morning that the day was the anniversary of her husband’s death. A year only. It had seemed like twenty years. For she was very young, and fairly rich, and much admired, and the life she had hitherto led had not prepared her to support loneliness and seclusion profitably. The shock of the sudden death had been terrible. She had thought that she should die of it; but she did not even fall ill; and there was the child whom she adored ; and later there had arisen a new interest.

The new interest, in the form of Major Harold Walsh, was at her elbow on this kind morning of sweetest spring; a middle-aged man with a handsome, hard face and a very tender manner. He had, as some may think inopportunely, chosen the anniversary of the husband’s death to make the widow an offer of marriage.

The widow had reminded him of what had happened on that day a year ago, had pointed out that she could not possibly entertain such a proposition so soon, had even cried a little when she spoke of her husband, but had in no other way discouraged the tender-mannered major with the hard face.

It would have been well-nigh impossible for a man to make an offer of marriage with a child of three years old clinging to her mother’s skirts and incessantly babbling in her mother’s ears, so the child with her nurse had been sent into the interior of the plantation in search of lovely clumps of primroses, said to flourish there, while the two elders wandered with slow steps and down-bent eyes upon the outskirts.

There they would have been content to wander for hours, perhaps, he begging for assurances which she with an only half-feigned, pretty reluctance gave, but that this agreeable dalliance was cut short by a sufficiently alarming interruption. She did not absolutely dislike him. She liked him—very much, even. That was well. Years hence, if he waited patiently—and he would try, he would try to wait—she might even get to love him a little. Was that asking too much? Well, not just yet, then; he had said he would wait. But he was not to go away unhappy? Not utterly discouraged? He need not, for what had taken place between them, debar himself entirely of the delight of her society, he might__? But at that instant of the Major’s soft-toned pleading, and of the widow’s low monosyllabic replies, a voice from out the plantation on their left smote sharply upon their ears, calling affrightedly upon Mrs. Eddington’s name. Following the direction of the voice, the mother, whose mother-love was and would always be the strongest passion of her life, fled into the wood. In two minutes she came upon the kneeling figure of the nurse; and the nurse’s white and terrified face was looking up at her across the unconscious form of the little child.

“I found her so,” the woman got out through chattering teeth. “I sat reading, and she ran to the other side of the tree. She was talking to me, and then she didn’t talk, and I went round, and found—this ”

With shaking fingers the mother tore asunder the broad muslin strings of the hat upon which the child lay, rent open the dainty dress at the throat: “Look at mother Milly! Milly, look at mother ‘ ” she called wildly, impatiently, angrily.

As if in answer to the passionate appeal the child’s eyelashes stirred for a moment on the transparent cheek—were still— stirred again, and the dark eyes, so like the dark eyes of the dead father, opened upon the mother’s face.

“Only fainted,” the gentleman who had been proposing to officiate as Milly’s step-father said. He was much relieved that the scene, at which he had looked on awkwardly enough, was over. That for a three-years-old child to faint was an unusual and alarming occurrence he did not of course understand. Certainly, if Mrs. Eddington thought it necessary, he would go for the doctor. He could probably bring him quicker than a groom. Should he carry the little Milly home first?

But the mother must carry Milly herself. No; nurse should certainly not touch her. Never again should nurse, who had let the child for a minute out of her sight, touch Milly. Nurse, surreptitiously grasping a frill of the child’s muslin frock, wept, silent and remorseful, as she walked alongside.

Once the child, who lay for the better part of the half-mile to her home in a kind of stupor, opened her eyes again beneath her mother’s frightened gaze, and was heard to mutter something about some flowers.

“She is asking for the primroses she had gathered ‘ ‘ Mrs. Eddington whispered in a tone of intensest relief. “Did you bring them, nurse?”

The unfortunate nurse had not brought them.

“Milly’s p’or flo’rs is dead,” Milly grieved, in the little weak voice they heard then for the first time. “Milly’s Dadda took Milly’s flors, and they died.”

To that astonishing statement the child adhered during the first days of her long illness, till she forgot, and spoke of it no more. For any questioning, she gave no explanation of her words. She never enlarged upon the first announcement in any way, nor did she even alter the form of the words in which she expressed it. She always alluded to the curious delusion with a grieving voice, often with tears. “Dear Dadda is dead, darling,” the mother said to her in an awed whisper, kneeling at her side. “He could not have come to Milly.”

“Milly’s Dadda took Milly’s flo’rs, and they died,” the sad little voice protested, and the child softly whimpered upon the pillow.

“The child can’t, of course, even remember her father,” Major Walsh said with impatience, being sick of the subject and the importance attached to it. “She was only two when he died.”

“How can you tell what a child of two remembers?” Mrs. Eddington asked. “She was very fond of Harry. I think she does remember.”

Of late, persistently in her mind was an episode of that last day of her husband’s life. He had carried his little daughter, laughing and prattling to him, down from the nursery and had put her in her mother’s arms. The child, when he turned to go, had clung crying to him: “Don’t leave Milly, Dadda. Take Milly too.” Laughing and kissing her, he had promised that, “Not now—not now—but later ’’ he would come to take Milly. Then he had gone out with a smile still on his face, and had fallen dead as he walked across the park.

It was inevitable that in these days London house, and they at last turned the memory of her husband should more fully occupy the young widow’s mind. He had died of heart disease; his child, it was now discovered, had a certain weakness of the heart. A superstitious feeling that she had not remembered him enough and that this was her punishment took possession of Mrs. Eddington’s brain. She remembered with remorse what was occurring at the moment the child had fallen insensible among the primroses. On the very anniversary of her poor Harry’s death she had forgotten him so far! Never would she forget him again.

The words the child spoke had recorded a mere delusion, the doctor told her, of the little dazed brain in the moment preceding unconsciousness; but, for all that rational view, they awed the mother, haunted her.

“Milly’s p’or flors is dead. Milly’s Dadda took Milly’s flo’rs and they died,” Milly had said.

Never would Mrs. Eddington leave her child or forget Milly’s Dadda again.

Yet, when the anniversary of poor Harry Eddington’s death came round again, Milly had been for three-quarters of a year running about as of old; and her mother had been for a month the wife of Major Walsh. They had spent their honeymoon at Major Walsh’s own place in Wiltshire, had stayed for another month in his London house, and they at last turned their steps in the direction of the home which had been Harry Eddington’s and where his child had been left under the guardianship of the New Mrs. Walsh’s mother.

“You used to complain of the dullness of the place and of how buried alive you were there. You have been away for eight weeks and you are mad to get back to it,” the husband said with a jealous eye upon her.

She subdued judiciously the joy which had been in her voice. “I am glad to see the old place again—yes,” she said. “Won’t it be delightful for us to be together there where we first knew each other?”

“It is the child you want—not me,” he said with grudging reproach. She found it necessary to make some quite exaggerated statements to reassure him.

Her mother was in the carriage which met them at the station. “Milly is staying up till you come,” she told them. “I left her capering wildly about the nursery with delight.”

“I hope she won’t over-excite herself,” the mother said, and the grandmother laughed at that anxiety. No child of hers had ever had a weakness of the heart, and she was inclined to ridicule the idea that Milly required more care than had been given to her own children.

Full of the longing to see her child, Mrs. Walsh sprang from the carriage and ran up the broad steps to the wide-open door of her home. Then, with a happy afterthought, turned on the mat and held out her hands to the new husband. “Welcome—welcome to our home, dear,” she said.

He grasped the hands tightly: “After all, I suppose I am a little more to you than the child?’ he asked.

She smiled a flattering affirmation, and at the instant there came a scream in a child’s voice from a room above, followed by an ominous silence.

When the others reached the nursery from which, as they knew, the sound had come, the mother was already standing there holding in her arms the unconscious form of the little girl. From a tiny wound in the child’s white forehead drops of blood were oozing.

“I left her for one minute to fetch the water for her bath,” the nurse was saying, hurriedly excusing herself. “She was running up and down and round about calling, “Mother, Dadda, come to Milly. Come Dadda, come!”

“She fell and struck her head against the sharp corner of this stool,” Major Walsh said. “Look, what sharp corners it has.”

The child was only unconscious for a minute. She opened her eyes and smiled upon her mother, and hid her face in her neck, and presently was whispering a question again and again in her ear.

Mrs. Walsh looked up in a bewildered fashion from the little hidden face: “What does she say?” the grandmother asked.

“She says, “Where is Dadda gone?’” the mother repeated, faltering a little over the words and with scared eyes.

“He is here,” said the practical grandmother, and took Major Walsh by the arm. “We have told her her Dadda was coming with her mother,” she explained. “She was more excited about him even than about you, Millicent. Look up! Here is your Dadda, darling.”

Slowly the child lifted the little throbbing head from the mother’s shoulder and looked at the big man with the hard face now stooping over her. Looked for half a second, then shut her eyes again, and again hid her face.

“It isn’t my Dadda,” she said with a baby whimper. “Milly wants my Dadda that came and danced with Milly. Where’s my Dadda gone?”

Later, when the child had been put to bed, the mother, having hurriedly dressed for dinner, kneeling by the side of the crib to hold her daughter in her arms, and kissing the tiny wound upon her forehead, asked how it was she had managed so to hurt herself.

“My Dadda came and danced. He whirled Milly round and round,” she said, grievingly. She knew nothing more of the occurrence, it was the only explanation she ever gave.

The look of awe which had been there once before came back to Mrs. Walsh’s eyes. Only to the doctor did she ever repeat the child’s words. He, being a man of good common sense, refused, of course, to be impressed with the coincidence.

“She made herself giddy by, as she says, whirling round and round. In the moment of losing consciousness—who can tell by what unintelligible mental process—the figure of her dead father, undoubtedly imprinted with unusual clearness on the child’s memory, was present with her. A vision, yes, if you like to call it so ; say rather a dream in the instant before unconsciousness. Such a babe as this knows no distinction between dreams and realities, between the momentarily disordered mental vision and the ordinary objects of optical seeing.”

For the rest, the unsatisfactory condition of the heart was still existent. Nothing that with care might not be obviated. With the absence of all excitement, with entire rest of mind and body the child would outgrow the evil.

Yet, in spite of this cheerful view of the case, it was long before Mrs. Walsh could successfully conceal the uneasiness and unhappiness she felt. Her punishment again, she told herself with morbid iteration. She had turned her back on her child, had forgotten her dead husband, nay, even in the moment of the child’s accident had she not been in the act of welcoming another man to that dead husband’s home?

So it came to pass that with a new life just begun for her and new interests arising on all hands she found her mind continually reverting to the days of her earlier married life. Often, when bent on any expedition with Major Walsh, dining with their neighbours, receiving them in her home, walking, driving with him, talking over the details of the business of her little estate, she was thinking, thinking how she and that other man had gone here and there, said this and that to each other. How he had looked, the words he had said, his gestures, his laugh came curiously back to her, and her heart sank beneath a constant sense of self-reproach. How could she not have remembered all this before and been true to the claim he had on her—that poor young husband who was the father of her child?

Once, but that was months later and she was weak in body as well as depressed in mind, she sat alone over her bedroom fire as the dark came on, too tired to dress, and longed for her husband to come in and cheer her. Then the memory came to her of how once before, a few weeks before Milly was born, she had so sat in that very room and had longed inexpressibly for that other husband; of how she had felt that she would die of fright and of unfulfilled longing if he did not come; of how he had come, bringing warmth and love and comfort to her failing heart; of how he had laughed, and said he had felt she was wanting him and so was there. And as she thought of this, lying with shut eyes in her armchair, a curious feeling that he was there again, with her in the room, took possession of her. She was not afraid; she lay quite still, hardly breathing, feeling “He is here! If I open my eyes I shall see him.”

And often, in the weeks that followed, she was haunted by that strange consciousness of her first husband’s presence, the curious, forcible impression that there was between her and him but a slight veil she lacked the desire to rend, but that, rending it one day, she should see him.

Then Harold Walsh’s child was born and these unhealthy fancies were naturally vanquished.

It was a son, and there was much rejoicing. Poor little Milly’s nose, it was said, must indeed be put out of joint by this advent of an heir to his father’s large estates. The child was born at Royle, his father’s place, and christened there, during which time the little Milly had stayed in her own home with her grandmother; the home where she had been born and her father and mother had passed their brief married life together. When the son and heir was two months old he came with his father and mother to stay in that house also. Then her mother and the neighbours who had known her through all her experiences of joy and of sorrow were glad to see that the Major’s wife had got back her health and spirits and happiness.

The boy was a fine boy, and his mother idolised him; the father, contrary to general expectation, continued to be very much in love. They were a prosperous and happy trio, seeming to suffice entirely to themselves; and little Milly, who had longed for her mother and the new brother, found herself of comparatively small importance and decidedly on the outside of the completed circle.

Who can measure the bitterness, the desolation, which no after experience of the unkind tricks of destiny can ever equal, of the little heart which feels it is not wanted where it longs to cling?

Then Milly’s birthday came and she was six years old: a delicate lovely child with dark, straight hair, and eyes of darkest greeny-grey, and a complexion which was as a finger-post to her father’s history and her own, and should have said “Beware.” Milly had always a birthday party, and this year also she must have one.

But it was not a party such as Milly had been promised; with the small drawing-room turned into a cave of delights where a real white-robed fairy with silver wings and a wand presided over presents to be given to Milly and all her little guests. The promise, in the pleasurable excitement of the Walshes’ arrival, had been forgotten by all but Milly, and when Milly demanded its fulfilment it was too late.

So the little guests could only dance— those that were big enough—or, assisted by their elders, in the form of governess or elder sister, play at forfeits and twilight, and blind man’s bluff. These innocent gambols they carried on in the wide entrance hall. Some flags had been hung, to please Milly, against the heavy beams of the ceiling, and the gardener had filled every niche and corner with hothouse plants. Being bent apparently on spoiling his sister’s pleasure the heir of the house of Walsh must be taken with a colic on that day. His mother was anxious about him, fancying him feverish, and insisting on the doctor’s presence. So it came to pass she was oftener sitting in the nursery, seeing her son jogged, howling lustily, on the nurse’s lap, than making merry with Milly and her friends in the hall.

As the afternoon drew to a close and carriages began to arrive for the children and their guardians, she came out of the nursery, and standing in the comparative darkness of the corridor, looked down upon the bright and pretty scene. The children in their dainty white dresses with their flushed faces and tossed curls were as lovely as the flowers everywhere surrounding them, the music of the chattering voices, of the clear laughter was more agreeable to the ear than that of the piano Milly’s governess was playing.

The fun, as is apt to be the case when such a gathering is nearly over, waxed livelier as the time came for the children to part. “Just one more game!” Milly’s high little excited voice was heard pleading—“only one more l’”

It was the old-world favourite they chose, and formed themselves into a ring, putting the littlest boy—boys were scarce among them and very small — in the centre.

It was in the midst of much laughing and chatter and noise that the two little girls on either side of Milly Eddington felt her hands turn ice-cold in theirs and slowly slip from their grasp. The next instant she had fallen to the floor between them—dead.

The doctor — luckily on the spot, attending to the baby-brother— was with her in two minutes. There was nothing to be done. She was dead.

She had been the loveliest and the gayest there, laughing her pretty, happy laugh, babbling with the rest. Several of the elder guests had apparently been looking at the child and listening to her, when all at once she had become silent, had sunk backwards and died.

This they who looked on had seen, but nothing more. Mrs. Walsh, standing alone in the shadow of the corridor and looking down upon the brightly-lit hall, had seen this:

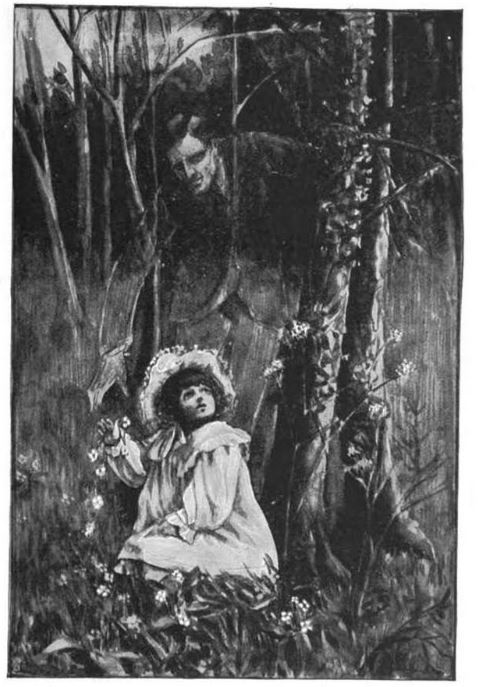

She had seen the figure of her first husband, the smile upon his face with which he had left her and her little daughter on the last day of his life, come silently into the hall. She had seen him, moving softly, attracting no notice from them, pass the groups of ladies standing near the walls, noiselessly thread his way through the ring of playing children till he stood at the back of his own little girl. She had seen him, smiling still, and clasping his hands tenderly beneath the child’s chin, pull her softly backwards, and lay her dead upon the floor.

The English Illustrated Magazine, Vol. 28, No. 230. November, 1902: p. 129-135

Previous posts for Father’s Day include Father Left a Picture on the Pane, Father’s Ghost Fetches the Dying, and A Man Buries Himself Alive.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.